An Iranian Cave, a Neanderthal Tooth, And an Ice-Age Murder Mystery

Lions, cave bears, and leopards, oh my!

Traces of Neanderthals live on in the DNA of modern humans, and their fossil record suggests a once-expansive presence across Eurasia. However, archaeologists are still trying to piece together just how widespread the extinct hominin species was in life. Now, analysis of a decades-old discovery in a remote mountain cave has confirmed suspicions that Neanderthals once roamed in modern-day Iran, expanding the range of our thick-browed cousins.

The research, which was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Human Evolution, based its findings on an artifact smaller than a thimble: a tooth. A child’s premolar, to be precise, originally found in Iran’s Wezmeh Cave following “clandestine activity” in 1999–in other words, looters disturbing the site in search of hawkable valuables. Only now, 20 years after it was recovered, has definitive analysis been conducted on the dental discovery. It is the first young Neanderthal’s tooth to be found in Iran. (The second, according to state media, was recovered last year in the same region.)

The Wezmeh tooth was discovered amidst an array of bones, few of them human. The other remains in the cave mostly belonged to Ice Age fauna—prehistoric bears, giant hyenas, wolves, cave lions, leopards, and more. Though the tooth was dated to a minimum age of 25,000 years old, researchers believe it’s considerably older, because the worldwide Neanderthal fossil record mysteriously stops around 40,000 years ago.

As far as scientists can tell, this child did not live in the cave. “Since the cave has a very low ceiling, and it is very narrow, deep and dark, Neanderthals could not use it for occupation,” says Fereidoun Biglari, head of the Paleolithic Department at the Museum of Iran and co-author of the paper, in an email.

How, then, did the lonely tooth end up in Wezmeh Cave? The answer is as grisly as you might expect. “The child most probably was killed by a carnivore,” Biglari says. “It is also probable that his carcass was found by a carnivore in the area and brought to the cave.”

Biglari says that, based on dating research, a range of carnivores inhabited the cave between 70,000 and 11,000 years ago.“In the early phase, the cave was used by bears for hibernation, some of whom died in the cave,” he says.

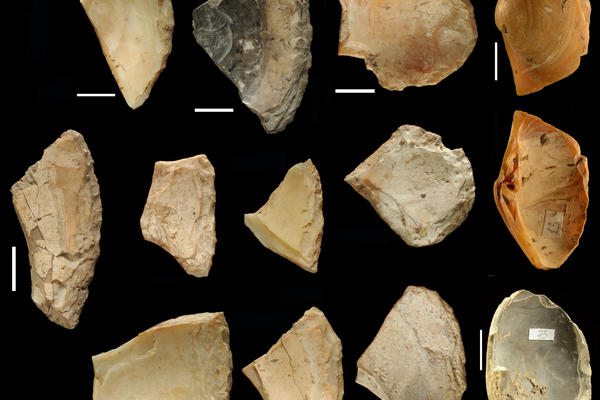

Though this prehistoric whodunnit may never be fully solved, the revelation of a Neanderthal tooth in the Iranian side of the Zagros Mountains is confirmation of a long-suspected presence of the species, previously hinted at by tools and other bone fragments.

“Wezmeh confirmed that [the] range of Neanderthals expanded into central Zagros,” Biglari says. “I expect that their range was expanded even further to the south Zagros where their stone tools have been found in numerous sites.”

Biglari’s hypothesis will be tested in the coming year with more work in the cave, according to Marjan Mashkour, an archaeozoologist with Paris’ National Museum of Natural History and co-author of the recent paper.

“We are looking more specifically on finding traces of human activities, although this cave was primarily a den for hyenas and bears who alternatively occupied it,” says Mashkour.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook