The ‘Pedestrian’ Who Became One of America’s First Black Sports Stars

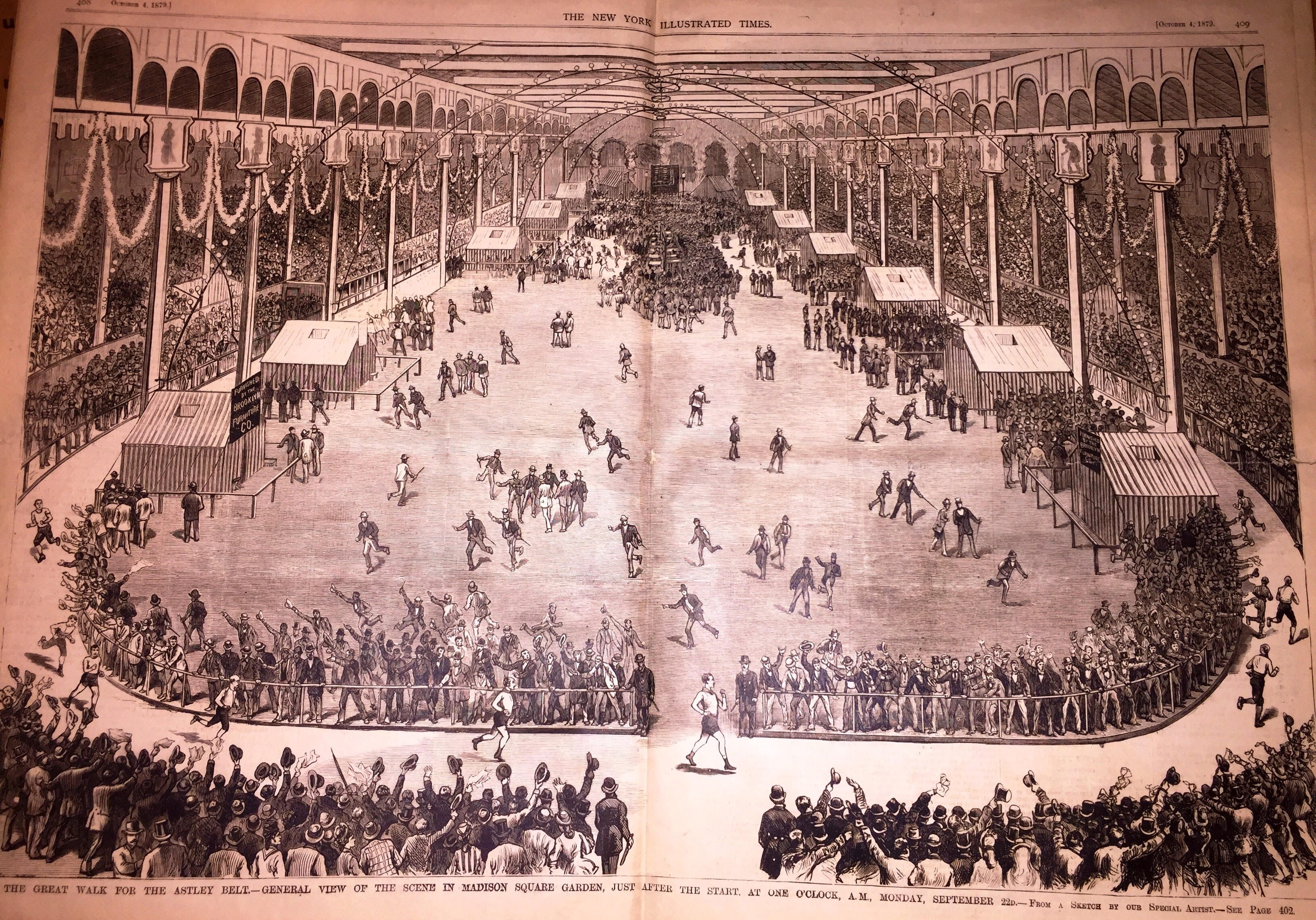

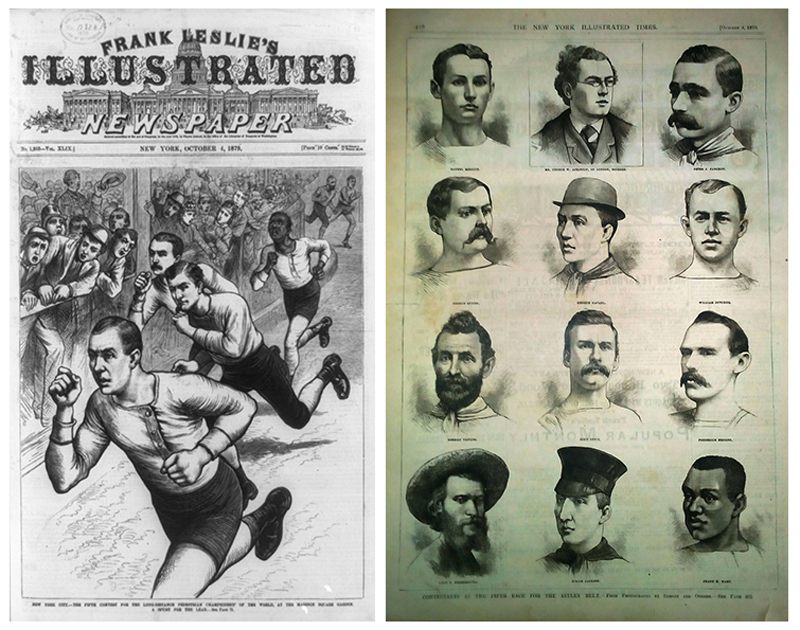

In 1880, Frank Hart wowed audiences at New York’s Madison Square Garden by walking 565 miles in six days.

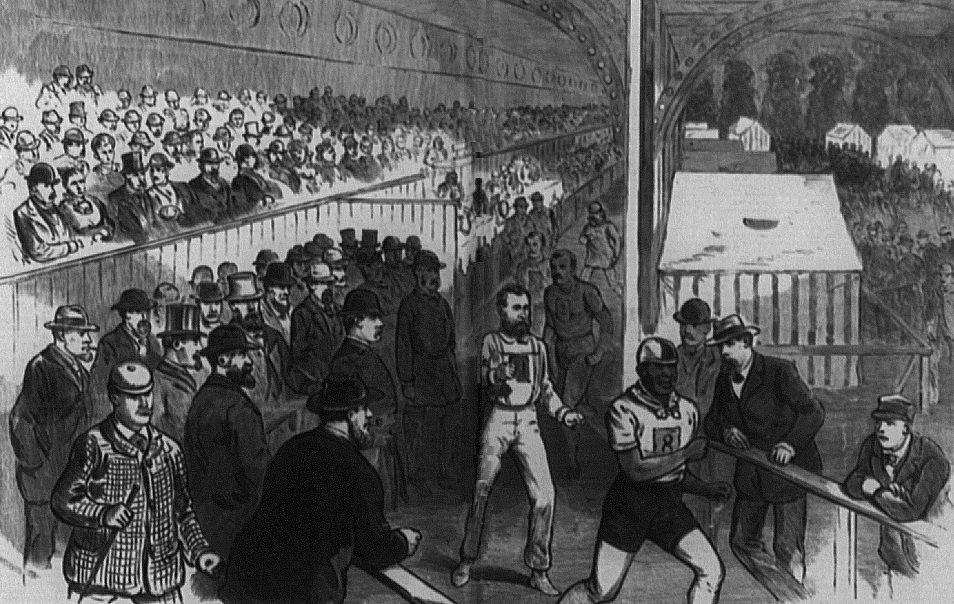

On April 10, 1880, New York’s original Madison Square Garden was packed with sports fans. Men in the arena roared. Ladies waved their handkerchiefs. A band struck up “Home Sweet Home,” the classic 1823 American folk ballad. They had come to see Frank Hart, one of the best “pedestrians” of his day.

“I’ll break those white fellows’ hearts!” Hart, an immigrant from Haiti, vowed before the race. “I will—you hear me!”

Eighteen men competed in the race. Three of them were Black*, including Hart. After Hart crossed the victory line, fans showered him with bouquets of flowers. His trainer handed him a broomstick to hold the American flag aloft during his victory laps.

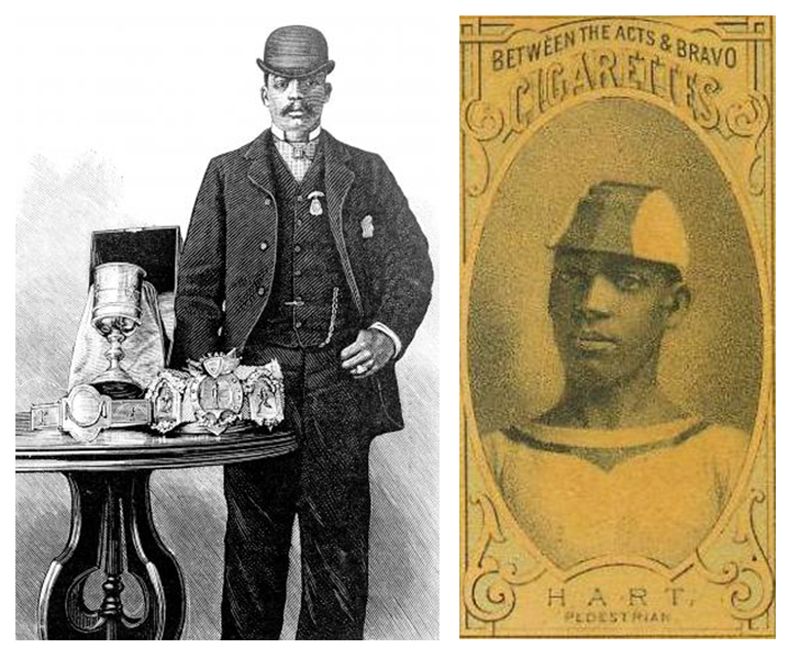

Hart had won a “six-day go-as-you-please” endurance race. “The rules were simple,” explained Mile High Card Company, a sports auction house, in 2010. “Participants, called ‘pedestrians’ were free to run, walk, crawl, and scratch their way around an oval track as many times as possible in the course of six days, sleeping on cots within the oval, and usually for less than four hours per day.” Hart set a new world record by walking 565 miles, or 94 miles per day. His prize was $21,567, including $3,600 he legally betted on himself. It was the equivalent of almost a half million dollars today.

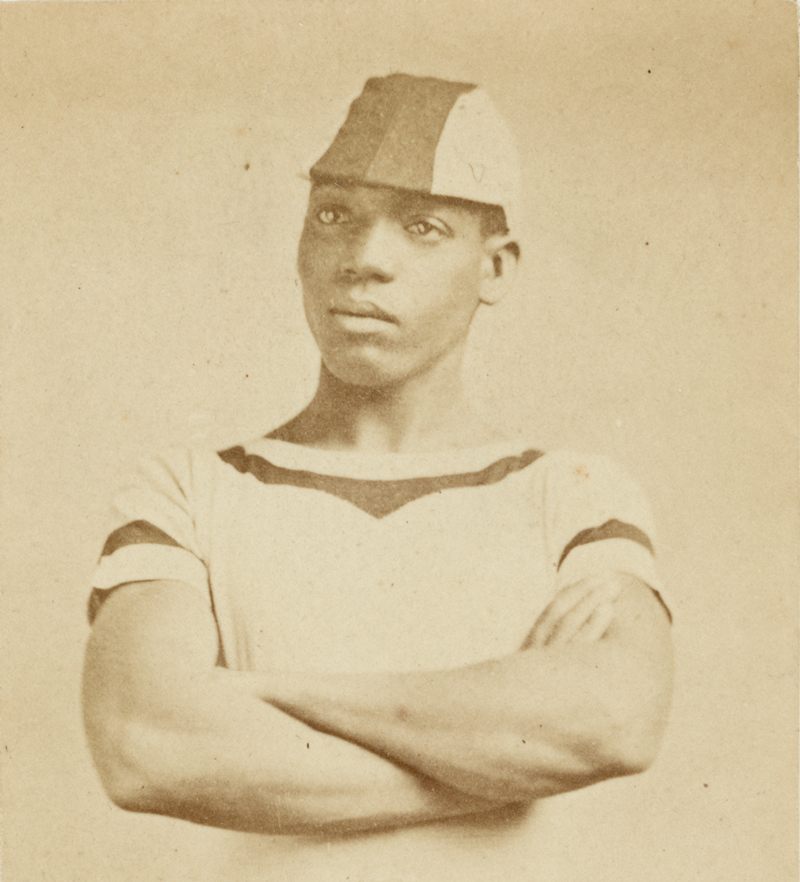

Hart broke racial barriers in sports just 12 years after African Americans achieved full citizenship with the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. And yet, in the 21st century, he has been largely forgotten. However, the recent discovery of a Frank Hart trading card, now for sale through Heritage Auctions, the nation’s largest collectibles auction house, has illuminated his legacy once more.

For a brief period from the late-1870s through the 1880s—at the dawn of professional baseball in the United States—pedestrianism was the national pastime. And Hart was one of its leading names.

After emigrating to the United States from Haiti sometime in the 1870s when he was in his teens, Hart worked in a grocery store in Boston. There, he began competing in local races to make extra money. Daniel O’Leary, a savvy Irish immigrant and sports promoter, who had previously held the record for six-day racing, spotted Hart’s talent and decided to finance his career.

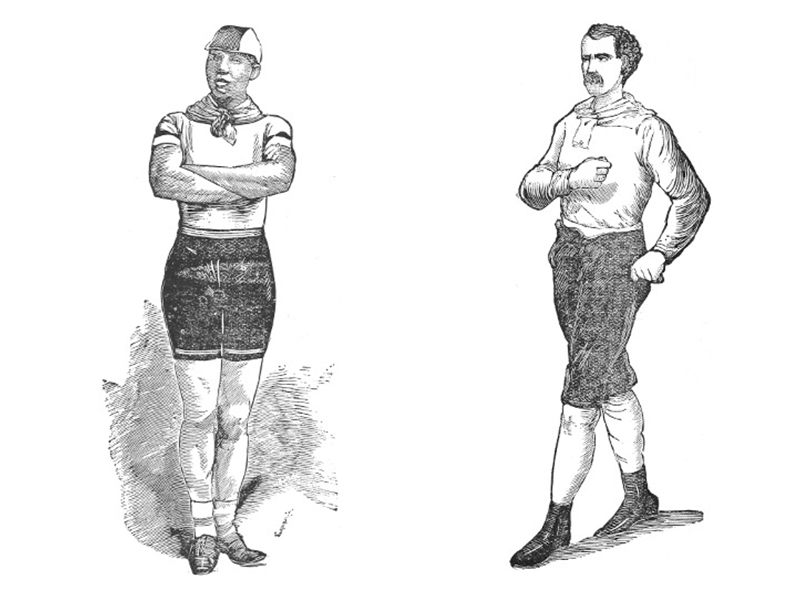

Hart’s given name was actually Fred Hichborn. But when he became a professional athlete, he figured “Frank Hart” had more of a commercial ring. The press soon nicknamed O’Leary’s client “Black Dan” because the two men shared similar racing styles. Newspapers also referred to him as the “Negro Wonder.”

While the national press was adulatory, it nevertheless wrestled with stereotypes. As documented in the book Pedestrianism by Matthew Algeo, a Brooklyn Daily Eagle editor saluted “Our Friend Mr. Hart,” whose exploits proved that “there’s nothing in a black skin or wooly hair that is incompatible with fortitude.” The Salt Lake Daily Herald headlined its laudatory story, “The Colored Boy Gets Away with the [Championship] Belt.”

Hart endured his share of racial abuse and violent threats from hostile spectators. Competitors refused to shake his hand at the starting line. An Irish rival with a brogue dismissed him as “the nagur.”

“[During a Boston competition,] a spectator tried to throw pepper in Hart’s face, though for reasons unclear,” writes Algeo. “The attack may have been racially motivated, though it may have been just as well motivated by gambling.”

There is some controversy among historians surrounding an attempted poisoning during a race in 1879 at Madison Square Garden. O’Leary firmly denied it, but in an academic paper titled “Old Time Walk and Run,” the historian Kelly Collins concludes otherwise: “After a spectator gave him some soda water he became severely ill and it was determined that he was poisoned.” Hart won the race anyway.

But the heyday of pedestrianism in America was short-lived. In the late 1880s, the craze gave way to baseball as the number one sport. A handful of Black ballplayers appeared in the major leagues in the mid-1880s before they were systematically banned by an unwritten Jim Crow system known as the “color-line” in 1887. By then, Hart’s best option to eke out a living as an athlete was to play professional baseball in the Negro Leagues.

During the 19th century, white baseball kept incomplete records, and the Negro Leagues kept virtually none. Hart thus suffers from the historical indignity of being unattached to a specific team. Most accounts simply link him to the nameless Negro League baseball team in Chicago. In May 1884, The Washington Bee reported that the “colored pedestrian plays shortstop for a colored baseball club known as the St. Louis Black Stockings.”

Hart should have been able to retire. “Keep in mind, in 1880 a good weekly wage in the U.S. was approximately $11, or less than $600 a year,” the journalist Kevin Paul Dupont wrote in The Boston Globe. “Hart’s take for that one [1880] event approached nearly 30 years’ worth of wages.”

Alas, he burned through his fortune. “Like many other sporting men, he was a big liver and a good spender,’’ reported the Cleveland Gazette in Hart’s obituary, as noted on Track and Field News. The Gazette revealed that Hart lived the last 20 years of his life off “the charity of friends.” Playing big league baseball surely didn’t help. Most white professionals played for very little money, and Black players for even less.

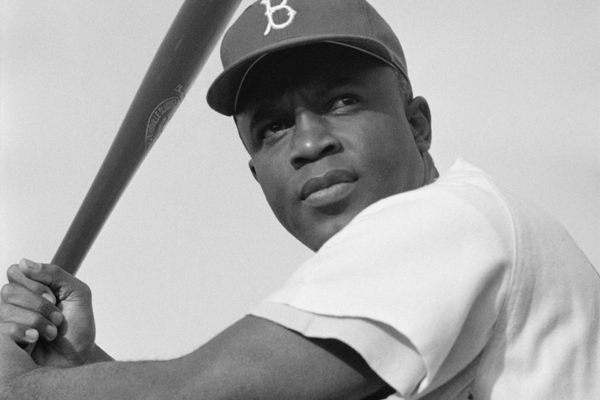

Hart died young, like other legendary African-American athletes, including Josh Gibson (known as “the black Babe Ruth”) who died at 36 and Jackie Robinson, who broke the color-line in 1947 by becoming the first African-American player in Major League Baseball in the 20th century. Robinson died at 53. The famed pedestrian took his final step at age in 1908 at 50 years old in relative obscurity. The cause of death was listed as tuberculosis.

In the collecting community, cards featuring Gibson and Robinson are highly collectible, but Hart’s are not, despite their extreme rarity. Heritage Auctions is selling what is believed to be only the third Hart trading card ever found. (The sale ends April 18, 2018.) Both were issued in packages to stimulate sales of cigarettes. Hart was certainly one of the first Black superstars featured on his own trading card. But while photo cards of Hart were in great demand in his heyday, very few of them have survived. In contrast to cards of baseball players, those of pedestrians were not keepsakes after the sport fizzled.

A contractor uncovered the latest Hart card, and 286 other sports and non-sports cards, while cleaning out an attic in an old house in Hartford, Connecticut. It is part of a rare sports set produced in Rochester, New York, by a company promoting a brand of cigarettes.

“Frank Hart should be remembered as a pioneer ultramarathoner who pushed the limits of human endurance,” notes Black Past, a digital reference guide to African-American history. “He offered hope that blacks and whites could compete against each other as equals. He was also wildly popular with thousands of spectators of all races who followed the sport.”

* Correction: A previous version of this story identified Frank Hart as African-American. He was Haitian-American.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook