The Passion (and Fantastical Fashion) of France’s Food Brotherhoods

Brie-shaped hats and colorful robes help culinary confréries promote regional specialties.

What compels groups of grown men and women in France to wear white plush hats shaped like huge wheels of brie? Or red capes with jagged green collars, making them resemble giant strawberries? Or even gray caps with long, squiggly white tendrils, signifying their love of pig intestines?

These aren’t the latest Paris fashions. Instead, such spectacular outfits symbolize a deep devotion to French food and produce.

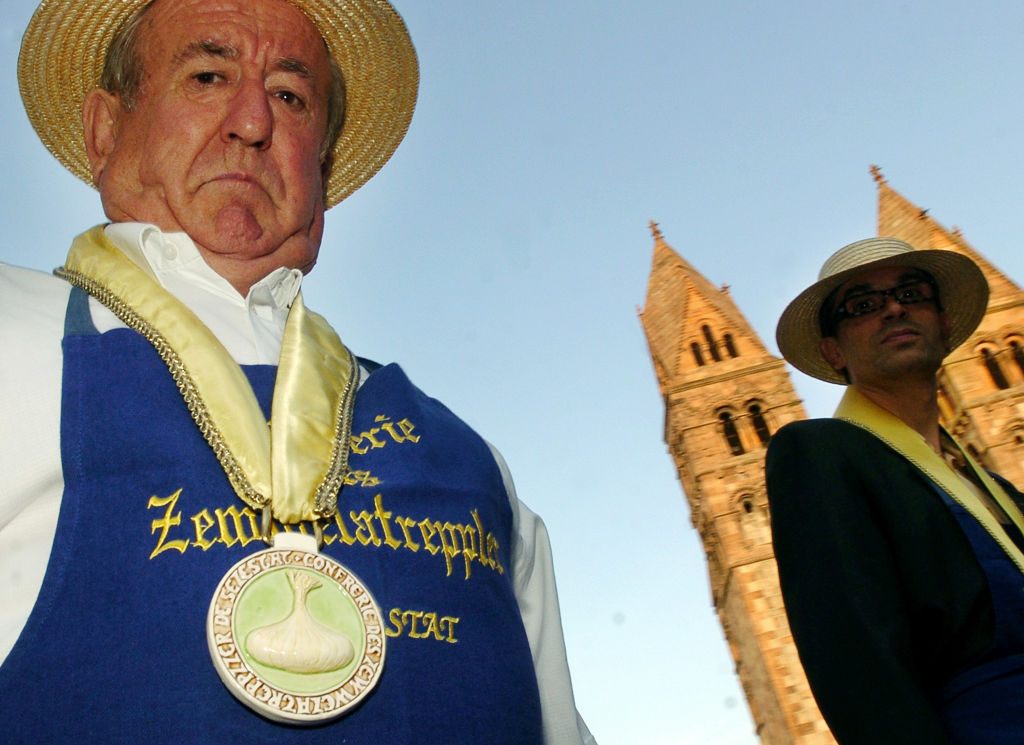

France is home to hundreds of confréries, or brotherhoods, devoted to local wine, liqueurs, fruits, vegetables, cheeses, or regional cooked specialties. Joining one of these volunteer groups is a serious commitment. When members are sworn in, they take an oath to support their local product. Often, they don headgear, medallions, and long robes whose colors and cuts reflect their beloved comestible. That can mean outfits that honor unique specialties such as pink garlic, or blue leeks. Their solemn duties include marching in processions, judging cooking competitions, and awarding prizes for the best farmer, chef, or restaurant upholding the glory of a particular edible.

Meaux, a charming town about 45 minutes from Paris, is home to the Brotherhood of Brie de Meaux, whose members sport the large brie-shaped headgear. Thierry Bitschené, a retired advertising executive, is the current president of the brotherhood. Member duties, he says, include promoting the benefits of the European Union’s PDO, or Protected Designation of Origin regulations, which establish standards and labeling rights for cheeses such as Brie de Meaux. “During visits to elementary schools, our role is to help young people discover PDO cheeses,” he explains. “We encourage them to appreciate their gastronomic heritage through tastings and classes.”

Festivals are another way these groups celebrate their products, often in collaboration with other local brotherhoods. At “Brie Happy!,” organized by the Brotherhood of Brie de Meaux in October 2022, members from 15 local confréries attended, mostly representing cheese, wine, and cider, plus one dedicated to pheasant terrine. Their annual competition brought together the country’s best brie-makers. whose creations were judged by a jury of eminent specialists.

Another brotherhood was born from the longing for a beloved pastry. Olivier Carbonneau, the grand master of La Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tougnol, is a celebrated rugby champion who grew up in the village of Chalabre, in southern France. As a child, he always loved the crescent-shaped anise flavored rolls called tougnol, but as an adult discovered that this treat had disappeared. Carbonneau and his determined fellow Chevaliers eventually sourced the missing recipe from the grandson of the village baker and resurrected it, selling this regional specialty at farmers’ markets and fairs. Their blue and gold outfits feature the city’s coat of arms, plus their favorite roll.

Most brotherhoods have a core group of one to two dozen official members. Additionally, they may count hundreds of supporters, such as well-known chefs, politicians, or sports figures who act as ambassadors to spread the love of each respective foodstuff. One illustrious example is La Compagnie des Mousquetaires d’Armagnac, which counts about 4,500 worldwide Armagnac “musketeers,” including famous members such as Prince Albert of Monaco, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Stanley Tucci.

Culinary brotherhoods are not a new thing. The Middle Ages saw a flurry of winemaker’s organizations, many authorized by French kings. In an era when poisoned wine ruined many a royal banquet by killing a guest or host, organizing groups of trusted master winemakers ensured these feasts could be drama-free. The members cultivated the vines, made the wine, and then tasted it, thus guaranteeing the drink’s purity—and the safety of the king and his guests. In 1248, King Louis IX of France also authorized a convention of goose-roasters.

In 1791, during the French Revolution, a law banned all such brotherhoods in the name of free enterprise. They were not reborn until the mid-20th century, when France’s post-war development allowed its citizens to rediscover their taste for the good things in life. At the same time, amid growing fears of the industrial food industry’s encroachment on authentic regional tastes came a need to protect local products.

Although these groups were originally male-dominated organizations, many now welcome female members. One group, La Confrérie des Taste-Sanciaux de Châtres-sur-Cher, which promotes an apple-stuffed pancake from Normandy, accepts only female members, who are provided with the secret recipe upon their initiation. “The men are just there to help set up and bring in the equipment,” said Hélène Degrigny, the marquise of the brotherhood, in a 2019 interview. “Otherwise the kitchen would be a mess.”

Along with the conviviality of parades and feasts, the purpose of these brotherhoods is to protect products linked to specific locales, safeguard ancestral recipes, and transmit them to younger generations. According to researcher Nathalie Louisgrand, decisive actions undertaken by the brotherhoods can safeguard French gastronomic heritage. For example, local French saffron was saved from oblivion by the Brotherhood of Saffron Knights of Gâtinais. After several decades of its absence, the spice is again cultivated in France.

Dominique Vignot is the Grand Master of the Brotherhood of Knights of the Genuine Camembert of Normandy. As a member for 10 years, her motivation remains the same: “To preserve, protect, and promote the terroir of Normandy and the art of making raw milk cheeses,” she says. In 2021, after a long legal battle, no longer can industrial Camembert cheeses be confused with the region’s raw-milk Camembert, as only the latter are authorized to wear the label “Made in Normandy.” “Our next goal is getting raw milk Camembert included on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list,” Vignot says.

Not all these groups undertake such serious projects. While most confréries celebrate a local wine, cheese, or other edible, a few confréries are dedicated to making and sharing gigantic versions of classic French dishes, such as a massive strawberry tart 30 feet long by 6 feet wide, or a humongous omelet.

The Confrérie Mondiale des Chevaliers de l’Omelette Géante de Bessières began its ritual in 1973, making a huge omelet once a year to share for free. This tradition is believed to be rooted in Napoleon’s love for an omelet he ate once in the town of Bessières.

Every Easter Monday for the past 50 years, the members of this brotherhood prepare a gargantuan omelet with 15,000 eggs, 22 pounds of salt, four gallons of oil, and a bucket of herbs. This tradition has now spread to six other French-speaking cities around the world, including Abbeville, Louisiana.

But in Bessières, the true meaning of the event is clear. Every year during the festivities, local children are taught how to make omelets, to ensure that the skill is passed on to the next generation.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook