When Food Dye Was Made From Coal Tar

It was considered almost magical.

For centuries, cookbooks written by upscale chefs explained how to make foods colorful. From spinach to ground-up azurite, food coloring came from compounds found in nature. But in 1856, an 18-year-old British chemist made a mistake in one of his experiments. That mistake marked the beginning of synthetic food dye.

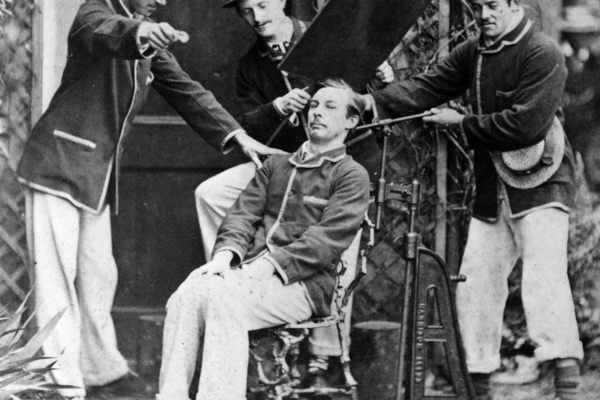

William Henry Perkin wasn’t trying to make Red #40 in his lab that day. As a research assistant for a famed chemist, he was trying to whip up synthetic quinine, a treatment for malaria. Perkin was interested in the properties of coal tar, an abundant byproduct of coke fuel, which comes from heating coal. But instead, he ended up with a dark powder. Washing out his flask with alcohol, Perkin was struck by the residue’s bright purple color. He tried using it to dye silk, and it was a success. Perkin had found the world’s first synthetic dye.

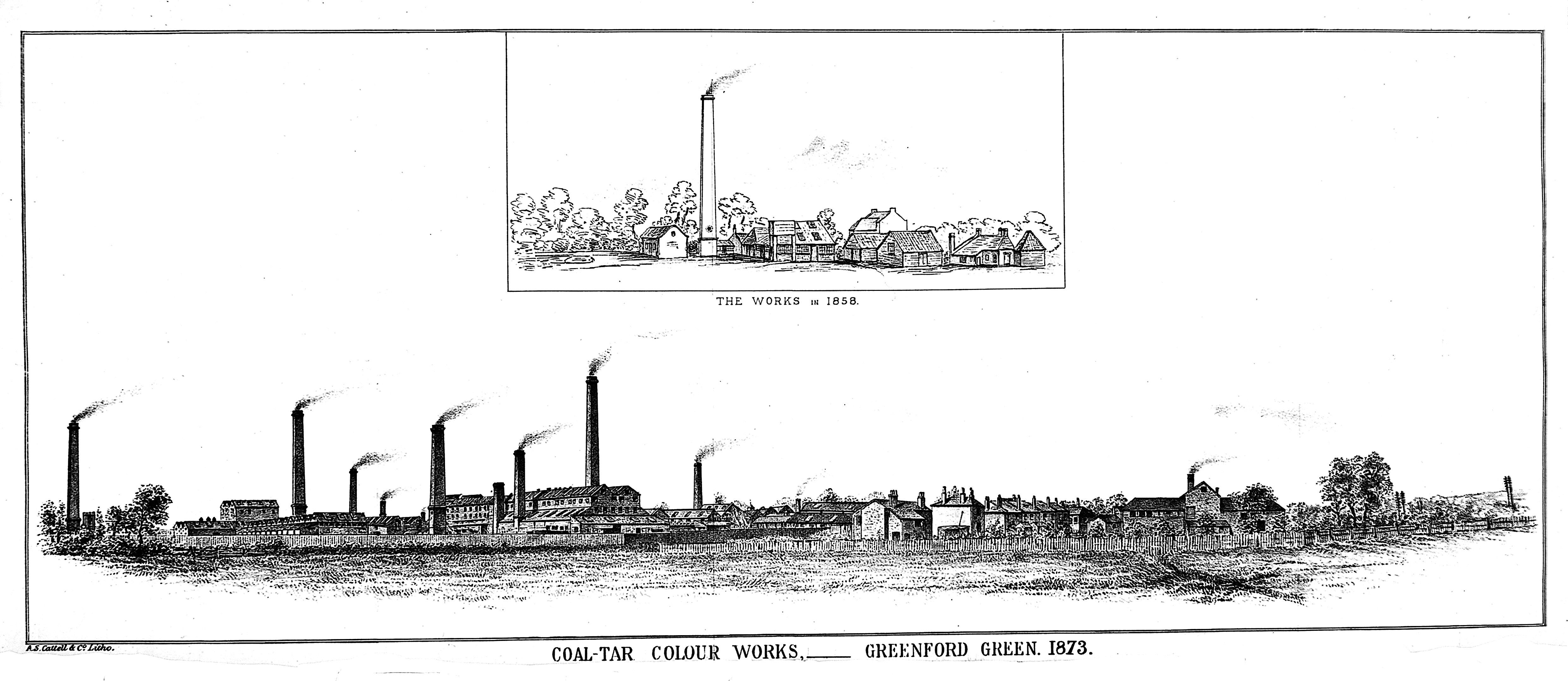

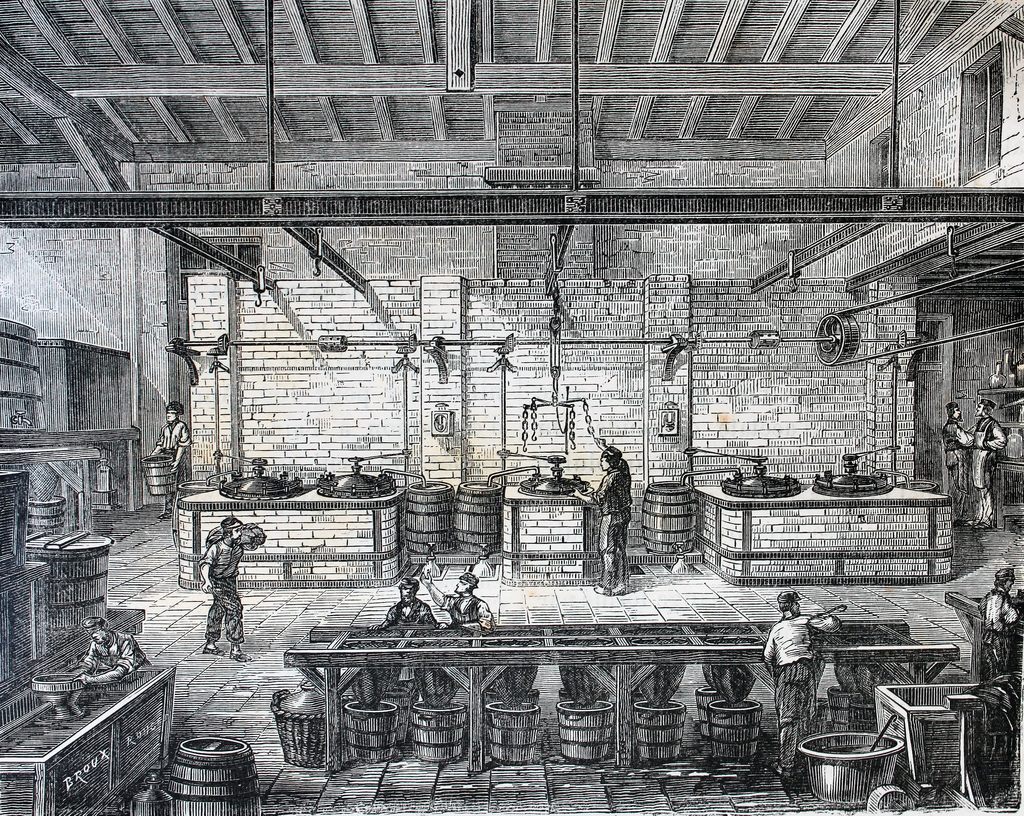

By the next year, Perkin and his family had started a company to churn out dyes. Soon, even Queen Victoria was seen wearing a dress made with Perkin’s synthetic mauve dye. Chemists raced to develop new coal tar-based colors, and all of the rainbow joined the first mauve shade. Often, they were known as “aniline dyes,” because they were derived from aniline, which itself was derived from the benzene in gloopy coal tar. Or simply “coal tar colors.”

The discovery was considered almost magical. Gas and coal companies had long dumped coal tar into waterways, and suddenly it was a source of beautiful dye. Perkin sparked a golden age of coal tar experiments, with chemists creating everything from artificial vanilla to skin medicines.

Food companies soon used the coal tar colors as well, especially in butter, candy, and alcohol. Though gross-sounding, they might have been healthier than the alternative. In both Britain and the United States, the 19th century was plagued with food adulteration, often in the form of food coloring. In order to make pickles, jellies, and candy more vivid, manufacturers added dangerous metal salts such as copper sulfate and lead chromate. In contrast, coal tar dyes were so vivid that only a little was needed. Plus, the tiny amount meant that the flavor wasn’t affected.

But coal tar colors were far from perfect. Workers in coal tar color factories developed bladder cancer. In the late 19th century, vibrant colors hid food imperfections, and food manufacturers used toxic ingredients to synthesize coloring agents. Harvey W. Wiley, chief chemist at the Department of Agriculture, fretted that too much butter dye caused kidney damage.

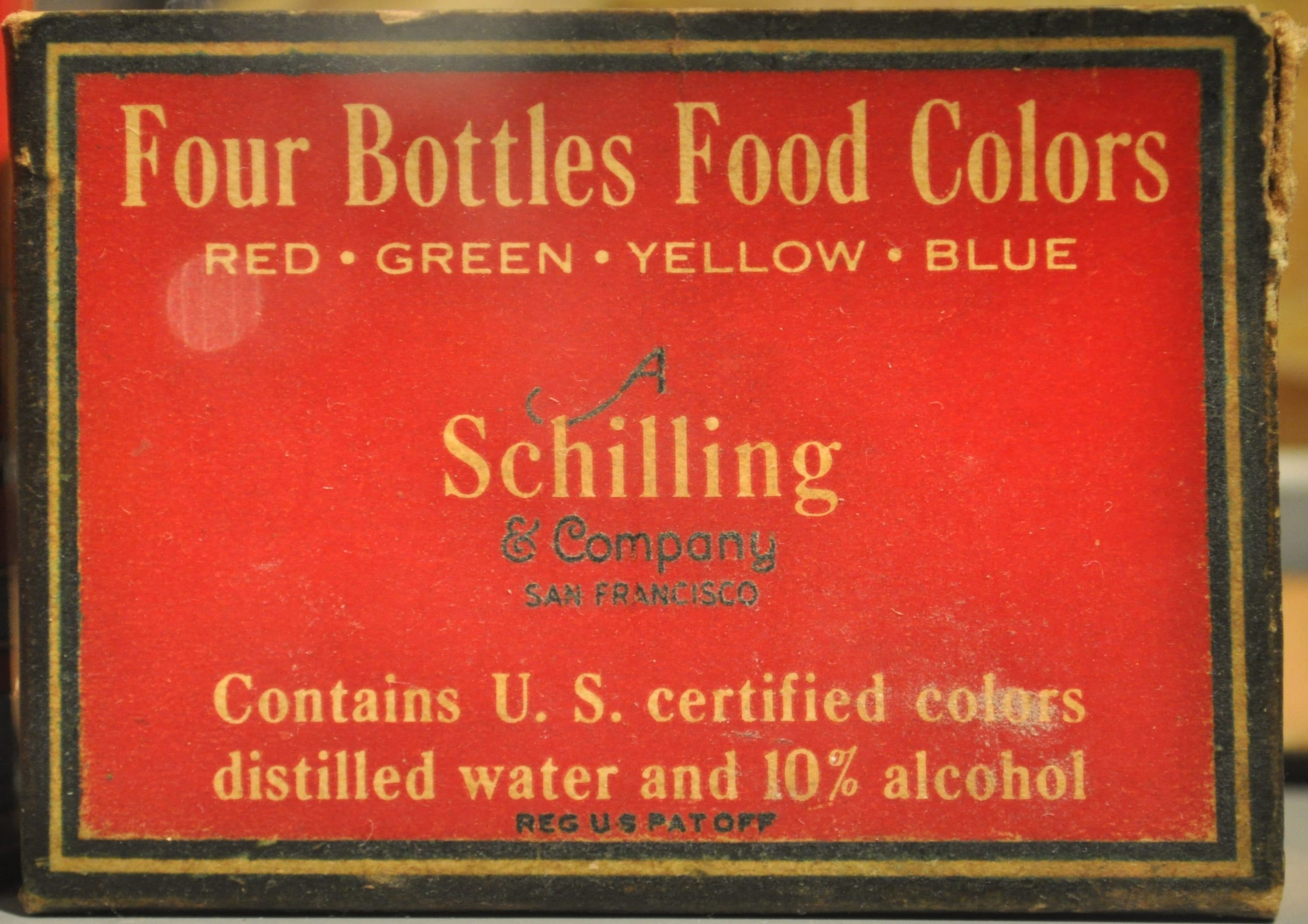

The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act empowered American regulators to decide which colors could be used for food, and they only approved seven colors. A writer for the The New York Times described with awe the difference: As manufacturers adjusted to the new rules, the “masquerade” was temporarily stripped away. Some formerly red, jarred cherries, for example, were naturally yellow. The coal tar dye used to brighten them had been banned.

Perkin also visited New York in 1906. Fifty years after his mauve discovery, hundreds of chemists celebrated the “magician of coal tar” at a dinner at Delmonico’s, the country’s most famous restaurant. The Americans all wore mauve bow ties in his honor.

A few days earlier, a reporter asked Perkin if he thought coal tar colors were safe to eat. Perkins refused to take a side, telling the reporter that if small amounts were used, there was no danger: The right amount of food coloring, he said, was so tiny that even a similar dose of deadly strychnine poison would be harmless. But he acknowledged that the colors were often overused.

Over the years, more colors were permitted—the number grew to 15 by 1931. The term “coal tar colors” persisted, even as the use of coal tar faded. By the 1950s, petroleum was replacing coal tar as the source of vibrant food coloring.

But they faced increasing scrutiny. Dozens of illnesses caused by brightly colored Halloween candy in 1950 led the FDA to strike coal tar colors Orange #1, Orange #2, and Red #32 from the list. Any potential renewal of their status was squelched when testing of all three colors made lab animals seriously ill. Twenty years later, another scare involved Red #2. Some tests showed that the color made female rats develop tumors. The backlash was so intense that some companies stopped selling red-dyed food for the next decade. The red M&M disappeared until 1987.

These days, most food coloring is derived from petroleum or crude oil instead. Though safer, there’s still suspicion that they have ill-effects, which range from causing hyperactivity in children to Yellow #5 acting as ad-hoc birth control.

To combat the stigma against food coloring, large food companies are now going back to the past. Before Perkin created mauve, the color was derived from rare lichens. So they’re researching spirulina and other “natural” dyes for safer pops of color. For now, though, your favorite, colorful treats still rely on rigs churning oil out of the ground.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook