The Global Diversity of French Fry Dips Is a Window Into the Way We Eat Today

Ketchup and mayo are just the beginning.

There is something about a french fry that begs to be dipped. Maybe it’s the fact that they’re shaped sort of like a finger, which is the ideal form for dipping. Maybe it’s that modern potatoes—at least those outside the Andes Mountains—are mostly neutral in flavor, and take to any combination of additions. Maybe it’s the external crispiness that cries out for a contrasting texture. There are dozens of well-known fry dips, all around the world, and they fall into several families—producing a web of unexpected global connections. You never really know where you are until you dip a fry and take a bite.

Before we get to that, let’s explore the much-disputed creation of this ubiquitous foodstuff. Potatoes come from the Andean region of South America, and Andean peoples have not only thousands of different varieties of potato, but also many, many ways of preparing them. In the pre-Columbian Andes, and even for awhile after European contact, the most common methods were boiling, roasting, and a freeze-dry method that produces a product called chuños. Deep-frying, and cooking in oil in general, is a relatively new thing for potatoes.

Cooking in oil has a long history in certain parts of the ancient world. There are mentions of frying in Apicius, a Roman cookbook with recipes that probably date back to the first century. Olive oil was the medium of choice in the Mediterranean, and was plentiful, but for most of the world, fat and oil were prized and expensive. Olives are unusual in that a simple press can extract their oil, whereas for most plants, you have to smash them, boil them, then quickly skim off the oil as it separates. It was expensive to render fat from animals, and both expensive and time-consuming to produce it from vegetables.

Outside the Mediterranean, up until the end of the Middle Ages or so, fat and oil were too important to be used simply to cook something else. They were treated more like meat: vital sources of calories, not something to be used to cook something else. Fat would be spread on starches like bread, or added to soups and stews. That started to change around the time of the Industrial Revolution, when new machines and methods for extracting oil emerged. Roll mills, in which two rotating cylinders press material between them, started to be used to efficiently squeeze oil from plant matter in 1750. The hydraulic press was created in the late 1700s, then solvents in the mid-1800s (though the first solvents were almost certainly not fit for human consumption).

This is all to say that deep-frying, which requires a great deal of oil, is a mostly modern method—so french fries are a mostly modern dish. A common legend states that french fries originated in the Namur region of Belgium, where locals usually fried fish. One particularly vicious winter, the legend goes, their river froze solid, and so desperate and hungry locals cut potatoes into small, fish-shaped pieces, and fried those. That story comes from a 1781 manuscript wherein the author states that “this practice goes back more than a hundred years already.” But it’s incredibly unlikely that anyone was even eating potatoes in Belgium in 1681, let alone using wildly expensive oils to cook them.

Culinary historian Pierre Leclerq instead suggests that french fries—which he clarifies as being deep-fried, and not shallow-fried in a pan like home fries—probably came around in the mid-1800s, following the widespread availability of plant-based oils around Europe. They likely were first sold as street food in Belgium, France, or both. It’s also likely that the concept of deep-frying potatoes evolved independently elsewhere, too. After all, once oil was more affordable, why use its browning and crisping abilities on just about everything?

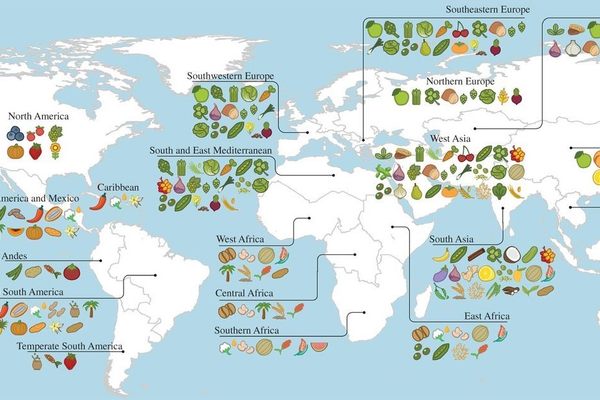

From there, the deep-fried potato—usually, but not always, in stick form—spread around the world. And so did its dips. Each fry dip is reflective of both local tastes and colonial conquests, new technologies and old traditions. The french fry is the medium through which you can see the parts that make up a modern culture. How you choose to flavor that most fundamental of snacks—deep-fried starch—says an awful lot about who you are. And it also shows how strangely interrelated world cuisine has become.

The state of the french fry dip in 2019 is wild: globalization has brought ketchup to the entire world, sure, but it’s also led to an almost impossibly large array of regional sauces and combinations. With that in mind, it doesn’t really make sense to break up the fry dips along geographic lines; the United States, dip-wise, has more in common with the Philippines than it does with Canada, for example. The world’s fry dips are better sorted by family.

The Creamy Family

This family of fry dips includes mayonnaise and its related sauces. Mayonnaise is, probably, an early-19th-century French version of aioli, which in its traditional egg-free form was found around the Southwestern Mediterranean and probably has its roots in ancient Rome.

Straight-up mayo is common as a fry dip in Belgium, France, and the Netherlands—perhaps suggesting it is a mother dip of sorts, though only one of several—and is widely used today all by itself. But there are dozens of varieties in this family, often much more exotic than a simple whipped white emulsion. Aioli or allioli—now often used as a shorthand for a garlic-heavy mayo sauce, though don’t tell that to the Spanish—is common on patatas bravas in certain parts of Spain. The Dutch make something called patatje oorlog, a dish of fries with, weirdly, both mayo and a peanut-y satay sauce. (It translates to “war fries.”) Remoulade, a mayo heavily seasoned with spices and often pickles, is common in Northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Then there are the spiked mayos: curry mayo (again, Belgium and the Netherlands), fritten sauce (heavily mustard-spiked mayo, from Germany), and, well, many other Belgian creations. Here’s one called “Brasil sauce” which has mayo, pureed pineapple, and curry powder. Koen Smets, a behavioral economist who was born and raised in Belgium and replied to a very vague tweet on the subject, says, “Most chip shops have an array of sauces, rarely less than a dozen, and often more than 25.”

This particular family is rich, mild, and lightly acidic. These creamy sauces are a foil for salt—fatty, with an excellent consistency for dipping, but no overpowering flavor. Devotees might say that it accents, rather than muscles out, the flavor of the fry itself. Those devotees might also scorn lovers of the next major family, and vice versa.*

The Ketchup Family

“Ketchup” is a Malay word to describe a Chinese sauce consisting mostly of pickled fish. The word and vague concept of a sweet-and-sour sauce made it to the United Kingdom, where it was made with mushrooms, and then to the United States, where it was made with that most glorious of New World fruits, the tomato.

Where the primary attribute of the Creamy Family is its fat content, the Ketchup Family is sweet, sour, and sweet again. Standard tomato ketchup is ubiquitous in the United States but pretty widely available elsewhere, with minor variations in sweetness, sourness, and acidity.

Like mayo, ketchup has a curry-spiked variety, most associated with Germany, and particularly with Berlin street food, though it’s also popular in Denmark, the Netherlands, and, yet again, Belgium. But ketchup doesn’t have to be made with tomatoes. Modern ketchup, really, is a fruit puree kicked up with vinegar, sugar, and spices. In the Philippines, banana ketchup (often dyed red) is a common dip. In Belgium, a version of a South Asian pickle is also common—something like a very sweet relish. It’s not pureed, like tomato ketchup, but given its status as a sweet-sour vegetable, it’s at least a ketchup cousin, maybe.

Throughout Southeast Asia there are chili ketchups, to be enjoyed blended or separately, depending on the diner’s taste. McDonald’s in Thailand, for example, has “American ketchup” and “chili sauce,” the latter of which is described as orange and tangy.

Brown sauce, a United Kingdom favorite, is a little trickier to parse. It looks like gravy (more on that family later), but is fundamentally a ketchup: tomato base, with vinegar and sugar. What separates it from standard ketchup is the additions: dates, raisins, tamarind, or any combination thereof, along with spices, a bit like what Americans consider steak sauce.

The key attribute of ketchup and its relatives, I think, is sugar. Ketchup has about four grams per tablespoon—more than vanilla ice cream (also a pretty good dip for fries). Ketchup, like mayo, has some acidity and an excellent viscosity for clinging to fries, but no other sauce on this list is anywhere near as sweet.

The Vinegar Family

This one usually comes back to the United Kingdom and places where its influence is felt. Probably the most iconic, though by no means the only, accompaniment to fries (chips) in the British Empire is malt vinegar, made from fermented beer, which also tastes good on the fried fish that often accompany them.

Vinegar fries are also fairly common in Anglophone Canada, as one might expect, as well as South Africa, where the British colonial influence is also felt. But they have a rather unusual way to do it: the South African slap chip, or slaptjip. This dish consists of a fry that’s been slathered in vinegar and salt and then, bizarrely, covered and allowed to steam—softening the fry and essentially taking away one of the key attributes of a proper fry, its crispy exterior.

The vinegar family is a curious one, as vinegar is, technically, a lousy condiment. The vinegar gets swiftly absorbed by the fry, meaning it can be difficult to taste if it rests for even a moment, and, of course, it tends to make a fry very soggy. The upside is a clean, crisp flavor, with no need to add fat or sugar, like the other families; just straight-up acid to counterbalance the oil.

The Gravy Family

Obviously the most famous member of the Gravy Family is the Quebec favorite, poutine, a mess of fries topped with cheese curds and brown gravy, usually a poultry stock thickened with flour or cornstarch. It’s salty, savory, and a little peppery. The American version of this is disco fries, most often associated with New Jersey, which replaces the cheese curds with shredded mozzarella. Gravies are essentially thick meat sauces, and in practice resemble a coating more than a dip.

There are other meaty sauces for fries, too, such as chili cheese fries in the United States, or poutine italienne in Quebec, which is basically bolognese sauce. These are all really more dishes than dips, as a proper dip should be served alongside the fries, rather than on top. But these variations are saucy and vital to understanding how fries are eaten. You might notice that these meaty fry dish–sauces are most common in cold regions. Surely there is a connection between the brutally cold Montreal winter and the desire to eat something truly decadent and ridiculous like poutine.

Interestingly, these are the only sauces served warm or hot; all the others are either room temperature or cold. This is mostly a technical issue; gravy congeals as it cools, which is pretty gross. Poutine cannot be eaten the following morning. (Trust me, I’ve tried.)

The Powder Family

Here’s where things get interesting. Heavily flavored powders that function like flavor-enhancing dips are common in Japan, India, the Philippines, and elsewhere. Sometimes fries are pre-spiced, like American “curly fries,” which are both curly and distinguished by a slightly spicy, paprika-tinted spice blend. Masala fries, from India, are like this, too.

In Japan, furaido potato are served with various powder seasonings and a bag; you add the fries and powder to a bag and shake the whole thing. Together they’re called furu pote, and common flavors include seaweed, butter soy, sesame, and more. Even McDonald’s sells them in Japan, as “Shake Shake Fries,” though a Japanese contact says that Wendy’s First Kitchen, previously known as First Kitchen prior to its acquisition by the American chain, is best known for its powdered fries.

The powder method is a highly efficient way to get bonus flavor onto a french fry. The powder is highly concentrated, so you don’t need much; it’s dehydrated, so it lasts forever; and because it’s dry, you don’t have to worry about soggification. On the other hand, you also don’t get any texture or temperature difference from a powder, but there’s no reason you can’t also dip a powdered fry.

It’s no particular surprise that the best-known powders come from Japan and India. Japanese cuisine is full of flavor-adding powders, including furikake (sesame seeds, seaweed, sugar, salt, sometimes other stuff) and shichimi togarashi (chili flakes, dried orange peel, sesame seed, ginger, seaweed, sometimes other stuff). Both of those, come to think of it, would be great on fries. India, too, is big on adding powders, in the form of spice blends, to pretty much any dish, from salads and popcorn to fried snacks and sandwiches.

The Outlier Family

There are various deep-fried potato-stick dishes around the world that don’t fit cleanly into these categories. The Bulgarian kartofi sus sirene is fries topped with shredded sirene cheese, similar to feta. In Peru, fries are sauteed with meats; lomo saltado is with strips of beef, salchipapas with, usually, slices of hot dog. Neither choice is really a dip, but both impart a great deal of flavor.

Then there’s the matter of reverse-colonial curry sauce, popular in the United Kingdom. It is made by frying garlic, ginger, onion, tomato paste, and spices before pureeing—like a Ketchup by definition, but it is not as sweet and is served hot, so it eats more like a Gravy. It offers something of both.

Deserving of special notice is Romanian mujdei, a garlic sauce that can be in either the Creamy Family or the Vinegar Family. The primary ingredient of this sauce is garlic, smashed in a mortar and pestle and mixed with oil (usually sunflower), sometimes with lemon juice or vinegar, and sometimes with sour cream. It’s simple, but still defies categorization.

Similar to mujdei is the Cuban mojo, made with crushed garlic, olive oil, maybe oregano, and citrus juice, most often bitter orange. But it is more likely to be eaten with a different fried starch, like yucca or plantain.

And finally, perhaps the greatest outlier of all. In Vietnam, french fries are often served with a side of butter and some white sugar. This is not so strange when you consider that fatiness is a defining trait of mayo and sweetness a defining trait of ketchup, and that just about every other staple food around the world can be eaten either savory, sweet, or both. Rice can be made into mochi or rice pudding; corn features in puddings and corn cakes; wheat can, obviously, be made into cake and about a million other treats. But the potato is hardly ever served sweet (Ed: A salty, crispy fry dunked in a cold, creamy milkshake is “chef’s kiss.”), though there’s no particular reason why. Hat’s off to Vietnam for just going for it.

* Update: It should be noted that Utahns prefer to mix the two.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook