From Zeus to Williams-Sonoma: The History of the Cornucopia

Do these classical nymphs even know it’s almost Thanksgiving? (Image: Wikipedia)

Well America, it’s almost that time of year again: time to haul out the decorative cornucopias.

Perhaps you’ll shell out for the $70 cornucopia at Williams-Sonoma. Maybe you’ll decide to forego the whole centerpiece thing. Regardless, you’ll be bombarded with images of woven cornucopias as the nation prepares to give thanks.

To most Americans, this bountiful horn is associated with the breaking of bread between the European pilgrims and Native Americans, or just simply the harvest season. But its history stretches back much farther than that. As seemingly all-American as this symbol of abundance is, the cornucopia has its roots in the mystery and magic of Greek mythology. What we generally see depicted today as a woven horn overflowing with flowers, fruits, nuts, grains, and all manner of wholesome symbols of domestic wealth, began as an animal horn. A magic animal’s horn.

A traditional Thanksgiving cornucopia. (Image: morano.vincent/Flickr)

According to the ancient Greeks, the horn of plenty, as the cornucopia was originally known, was broken off the head of an enchanted she-goat by Zeus himself. As the myth goes, the infant Zeus was hidden away from his father, the titan Cronos, in a cave on the isle of Crete. While in hiding, the baby Zeus was fed and cared for by Amalthea, a figure alternately depicted as a naiad (water nymph) or she-goat. Whether Amalthea was the goat herself, or just its caretaker, most of the myths agree that Zeus, while suckling at the teat of a magic goat, broke off its horn, which began to pour forth a never-ending supply of nourishment. Thus the symbol of the horn of plenty was born.

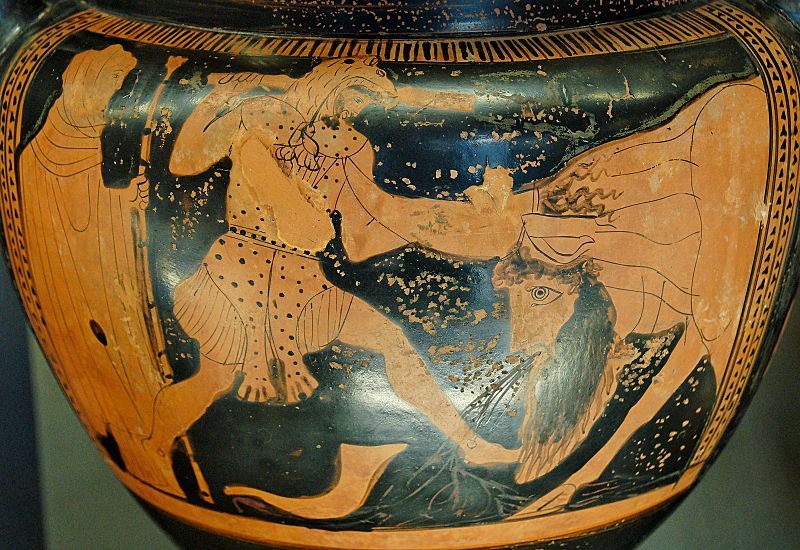

The ancient Romans, in their bid to appropriate the mythology of the ancient Greeks, told the story a bit differently. According to Ovid’s mock-epic poem, Metamorphoses, it was Hercules who created the horn. In the poem, the hero Theseus comes upon the moping river god, Achelous, and notices that one of his horns is missing. The pouting river spirit then tells the tale of how he battled Hercules over the hand of a woman, and in the end Hercules snapped off one of his horns. Nymphs filled it with “the choicest fruits of the autumn,” and it became the holy symbol for plenty. For the record, in the story the nymphs and choice fruits provide no joy to the defeated Achelous.

Hercules breaking off Achelous’ horn. For Thanksgiving. (Image: Wikipedia)

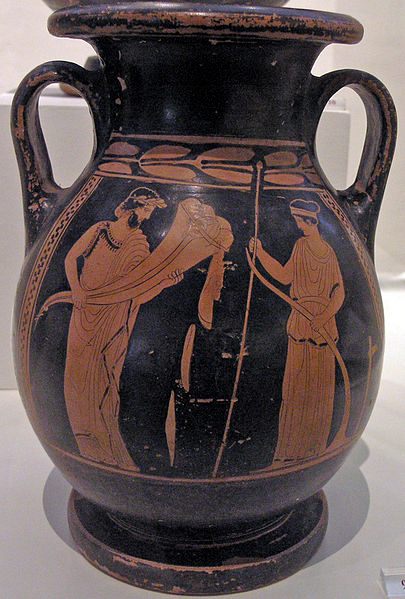

In addition to its specific origins, the horn of plenty became a symbol of wealth and abundance linked to mythological heavy-hitters Demeter, Goddess of the Harvest, and Dionysus, God of the Awesome Party, but it also became aligned with a number of minor gods in both the Greek and Roman pantheons. Most of the goddesses associated with the horn, which is itself a symbol of fertility, were patrons of luck, a bountiful harvest, or wealth. They had names like Abundantia, Fortuna, and even Copia, the goddess whose name can still be found in the word “cornucopia”—“cornu” meaning “horn” in Latin.

Demeter watches as the horn of plenty spills over. (Image: Wikipedia)

Even after the end of the Classical Age, cornucopias continued to pop up over the centuries in depictions of the classical gods, such as a 17th-century Rubens painting of the goddess Abundantia.

Abundantia was all about the cornucopia. (Image: Rubens painting ca. 1630/Wikipedia)

Thanks to its appearances in artwork that portrayed pastoral abundance, the cornucopia became a symbol of the harvest season, and its image morphed from its origin as an actual horn to just a horn-shaped basket. It also became a more common physical artifact found at harvest festivals.

Williams-Sonoma’s Fall Cornucopia. $69.99. (Image: Williams-Sonoma)

Today the horn of plenty is so ubiquitous it can be found on coats of arms from Colombia to Australia. To the American eye, the cornucopia means Thanksgiving, though it is unclear exactly when the cornucopia became associated with Turkey Day. It’s not impossible that there was an actual cornucopia at what is considered the original Thanksgiving, a three-day harvest festival in 1621, but there is no record of the decoration.

Regardless of when it first entered America’s symbolic lexicon, the cornucopia is here to stay—and available for an inflated price at your local upscale homewares store. This year, when you are giving thanks, be sure to give a shout-out to the angry classical gods who made one of the most iconic parts of the holiday possible.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook