Years Before Stonewall, a Chef Published the First Gay Cookbook

It was the first to be marketed to gay men.

On January 21, 1966, Time magazine ran a story entitled “The Homosexual in America.” The anonymous author criticized the growing activism and visibility of gay people in America, noting that many of them “apparently do not desire a cure” for their sexualities. As an example, the author referenced advertisements for a new publication: The Gay Cookbook by Lou Rand Hogan, a book that made no apologies in presenting an image of happy men cooking elaborate meals for their lovers.

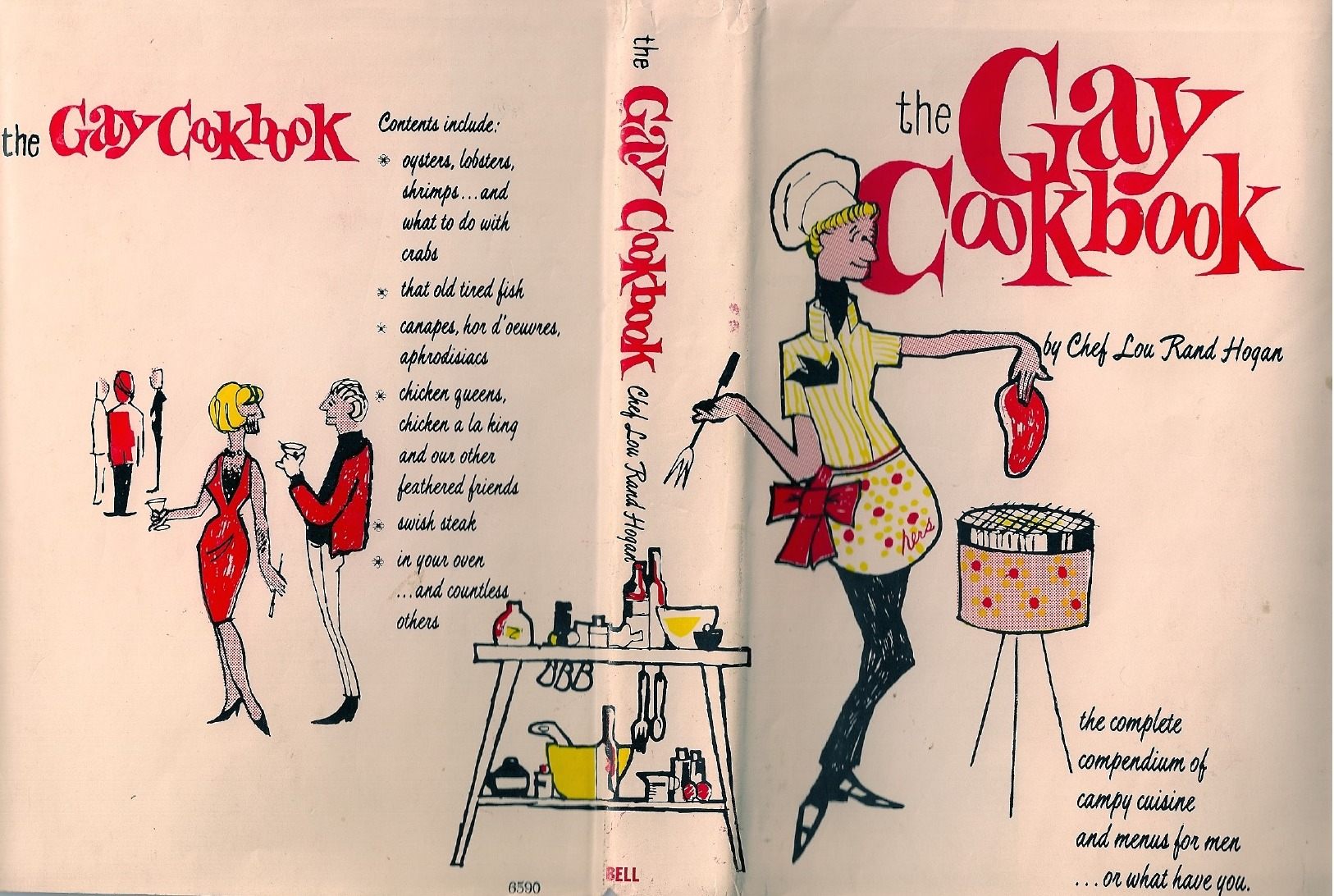

It was published on the cusp of a historic turning point, and copies of the book can still be found online and at many used bookstores. The bold cover has a colorful illustration of a blonde man in a flower-covered apron, grilling steaks, while the back features a hirsute person in a red cocktail dress. It was published years before the Stonewall riots ignited the gay rights movement in America, and at the time, widely advertising a cookbook for gay men was fairly edgy. But the author of The Gay Cookbook was no stranger to the gay publishing scene. In fact, five years before, he had published what is now believed to be the first detective novel with a gay protagonist, titled The Gay Detective.

Who was Lou Rand Hogan? One of the few things known about him is that his name was a nom de plume, says Stephen Vider, assistant professor at Bryn Mawr College and author of an academic paper on The Gay Cookbook. Most of our limited information about Hogan—such as that his name was actually Louis Randall, and he was born in Bakersfield, California, in 1910—comes from his own writing. He was the son of an oil driller who spent years abroad and eventually divorced his mother to live in Southeast Asia.

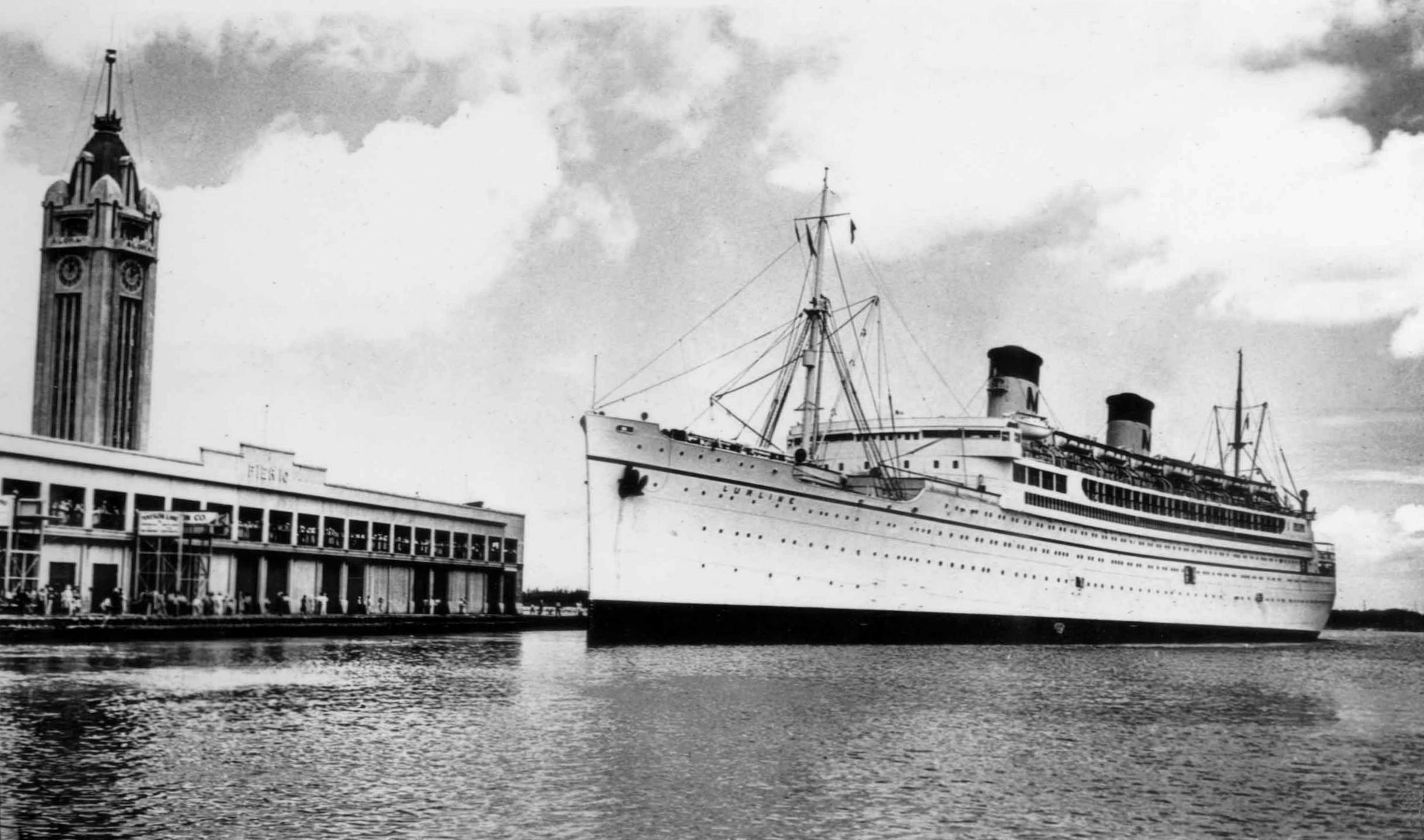

As a young man, Hogan became interested in theater, performing in chorus lines up and down the coast. In the riotous theater scene of the 1920s, he took on one of his first alternate identities, the stage name Sonia Pavlijej. But his theater career was unsuccessful, Vider says, and in 1936, he began working as a steward and cook on the new luxury Matson cruise ship line. “That’s really where he learns to cook,” Vider says.

The career move was opportune: In a short memoir, Hogan estimated that the vast majority of the stewards employed by Matson were gay. Not only was Hogan learning about the high-class continental cuisine that he would later describe in The Gay Cookbook, he also was immersed in “camp” culture—what Vider describes in his paper as “adopting or accentuating mannerisms and linguistic styles coded as ‘feminine.’”

Vider doesn’t know how Hogan became a writer: Although Hogan claimed later in life to have written on food for Gourmet and Sunset magazines, Vider wasn’t able to find any articles definitively written by him. However, the loosening of censorship laws in the 1950s meant that publishing gay and lesbian literature became more common. Hogan’s The Gay Detective was meant to capitalize on this newly available consumer market. The Gay Detective was republished in 2003, in response to growing interest in its thinly-veiled depiction of gay life in midcentury San Francisco. But the foreword to the new edition of The Gay Detective notes that Hogan’s real claim to fame would be The Gay Cookbook.

The 280 pages of The Gay Cookbook are filled with the jokes and innuendo of the time. Even on the frontispiece, in the book’s first pages, a line reads “All rights reserved, Mary.” (An essential part of mid-century campy dialogue, Vider says, was the use of female nicknames among gay men: Hogan addresses the reader by many, including Myrtle, Mabel, and Mame. “Mary” also served as a sometimes-derogatory term for a gay man.) The recipes are lengthy and chatty. But while written humorously, the recipes often are complex and cosmopolitan.

Hogan, after all, had sailed all over the world. While his repertoire includes French and American classics, it also features Mexican, Southeast Asian, and Hawaiian recipes. For a guacamole recipe, Hogan gives the basics as avocado, tomatoes, fresh lime, and salt. Those wanting to mix it up can add onion and spices, he writes, but he forbids more variation. “This is an ‘original’ Mexican recipe,” he writes, “before it’s been crapped up by some Hollywood or Brooklyn chef.”

But guacamole is on the easier end of the scale. Hogan also explains how to prepare an elaborate rijsttafel buffet, a many-coursed Indonesian banquet with roots in Dutch colonialism. A chili recipe spans several pages and requires hours of cooking.

Much of the book, though, is concerned with economical cooking, suitable for gay men living and entertaining solo. While Logan explains the basics of Spanish paella, he doesn’t give a recipe, noting the price tag of both seafood and saffron. He also instructs readers to learn to cook with cheaper cuts of meat, and to make friends with the local butcher. “Don’t swish into his market,” Hogan orders. Instead, he suggests, “Smile at the S.O.B. as you gayly ask, ‘How’s ya meat today, Butch?’”

Hogan turned out to be a culinary trailblazer. “In terms of his public role, I think that he imagines himself as kind of a gay Julia Child,” Vider says. In the introduction to The Gay Cookbook, Hogan describes a perhaps-fictional conversation with an editor eager to hop on the cookbook publishing wagon. The editor states that he’s heard one in six people are gay, so there’s the potential to sell a lot of books. Vider also points out that while there were other LGBT cookbook writers before Hogan, such as Alice B. Toklas, James Beard, and Craig Claiborne, The Gay Cookbook was the first “targeted to to gay men, [while] presenting an image of what gay life might look like to a larger audience.”

Despite Hogan’s humor and the advertising strategy, which presented the book as a curiosity, Vider says The Gay Cookbook promoted an image of gay domesticity. Vider, who is working on a book called Queer Belongings: Gender, Sexuality and the American Home after World War II, notes that gay men were often depicted as isolated and unhappy, with life “really centered on bars.” By depicting gay men cooking and entertaining for lovers and friends, Hogan presented an alternative image of gay domestic life as “a vibrant space of connection and community.”

In 1970, Hogan became a food columnist for The Advocate, a gay publication based in California. Hogan wrote a column, Auntie Lou Cooks, for nearly the rest of his life (he died in 1976), and Vider describes Hogan’s style as that of “a gay elder” reflecting on a campier past. Even in The Gay Cookbook, Hogan semi-jokingly, semi-wistfully describes the “seriously-formal dinners, soirees, grand drags, etc” of the 1920s, while noting that the 1960s were more casual, both sex- and food-wise.

For a younger generation of LGBT people, aspects of Hogan’s gleeful camp were outmoded. By the 1970s, “gay liberation activists really derided this kind of gay culture for indulging in regressive gender norms,” Vider says. For them, Hogan’s domestic vision would have seemed too consumerist and even “effeminate.” Plus, The Gay Cookbook targeted white men, and the illustrations by David Costain depicted minorities as racial caricatures. “It’s a very white book in terms of how he’s presenting gay culture,” Vider notes.

In other ways, The Gay Cookbook was ahead of its time—especially in its depiction of gay men living joyful lives in an era of repression. In his books and his column, “there’s not only a celebration of gay sociality, or gay social life, but also a celebration of gay sexuality,” Vider says. For Hogan, even one-night stands could be capped off with a homemade omelet. Though it’s hard to say what kind of person Hogan was, outside of what he wrote about himself, Vider likes to think he was gregarious and cheerful. Only someone “excited to be a part of a gay world,” as Vider describes Hogan, could have written The Gay Cookbook.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook