When Family-Owned Gelato Shops in Italy Almost Went Extinct

Did Big Gelato try to wipe out artisanal stores in the 1950s?

The signature chocolate sour cherry gelato at Vivoli, the oldest gelato shop in Florence, Italy, is made with an abbondanza of fruit, declares Silvana Vivoli. As the institution’s third-generation gelato maker, Vivoli specializes in making a distinctive stracciatella (whose secret, she reveals, is a hint of added cream) and the mandarino, which delivers a tang of citrus to the tongue. Every morning, Vivoli whips up the desserts in her shop’s kitchen, all the while remembering her father Piero’s lessons: That good gelato requires time, effort, quality ingredients, and a personal touch.

But what if gelato came in the same flavors, and without an abbondanza of anything? That almost happened just after the Second World War, when a new product, Mottarello, arrived. As the very first industrial ice cream in Italy, Mottarello wasn’t there to coexist with artisanal gelato. It attempted to replace gelato altogether—and almost succeeded. “The idea,” Vivoli says, “was to kill artisanal gelato.” As Luciana Polliotti, curator of the Carpigiani Gelato Museum in Bologna, Italy, puts it: “These were important years because it was like David versus Goliath, and David won.”

Although gelato had been invented several hundred years before the 1950s, it was originally just served for wealthy folks at banquets. Gelato didn’t become widely available to the public until the end of the 19th century. Most of these gelato shops operated as small family businesses well into the 20th century, but it became tougher to make a living hawking the dessert during the Second World War. (Once, the Vivoli family had to buy sugar on the black market, and ended up with a very expensive barrel of sand instead.) Post-war conditions for gelato shops weren’t much better, Polliotti explains, because Italians were so strapped for cash.

Throughout the 1950s, industrial ice cream—already all the rage in the U.S.—also had ambitious plans to corner the market in Italy. Polliotti says that during this tense time, sales reps approached artisanal gelato makers with a proposition: We’ll pay you to stop producing gelato and become our retailers. When they refused, non-industrial gelato suddenly—and suspiciously—began generating bad press.

By the summer of 1953, widespread claims that artisanal gelato was hazardous to one’s health were impossible to miss. According to a compilation from the historical archive of Gelato Artigianale Magazine/Levati Editori, a bevy of articles from the time emphasized that people kept getting food poisoning from gelato. “41 intoxicated near Siena by spoiled gelato,” blared one headline in Corriere della Sera (though the story notes that it just “seems” as though gelato was the cause). The same paper soon reported on a grandmother and granddaughter who both became ill after eating gelato, though they were expected to recover quickly. The very next day, Corriere della Serra broke news that 500 people had contracted food poisoning in Tivoli—an event that was blamed not on the food, but rather on the people who had handled it.

There must have been some bad gelato out there at the time—especially as this happened before many food safety innovations and regulations were ubiquitous. Yet what stood out was the singular focus on a specific food, says Polliotti. “Any kind of sanitary problem that burst out was attributed to artisanal gelato,” she explains. (That didn’t stop Audrey Hepburn from enjoying a gelato cone in 1953’s Roman Holiday, which Polliotti says “contradicted dozens of articles with one scene.”)

She also notes that the majority of damning articles appeared in Corriere della Sera and Il Sole 24 Ore, two papers from Milan. It’s worth noting that the city is also the birthplace of Motta, the company behind Mottarello.

The Motta ice cream brand has since changed hands multiple times, so it’s hard to know if executives had a hand in perpetuating this negative coverage. But there’s no doubt that they took advantage of it. “As you can imagine, there will always be a friction between artisanal and industrial gelato,” says Gustavo Stante, the Italian marketing manager for Froneri (which took over the brand in 2016). What Motta realized at the time, he explains, is that there was a need for something “more innovative and interesting” for customers, and designed its ads to convey how different these products were.

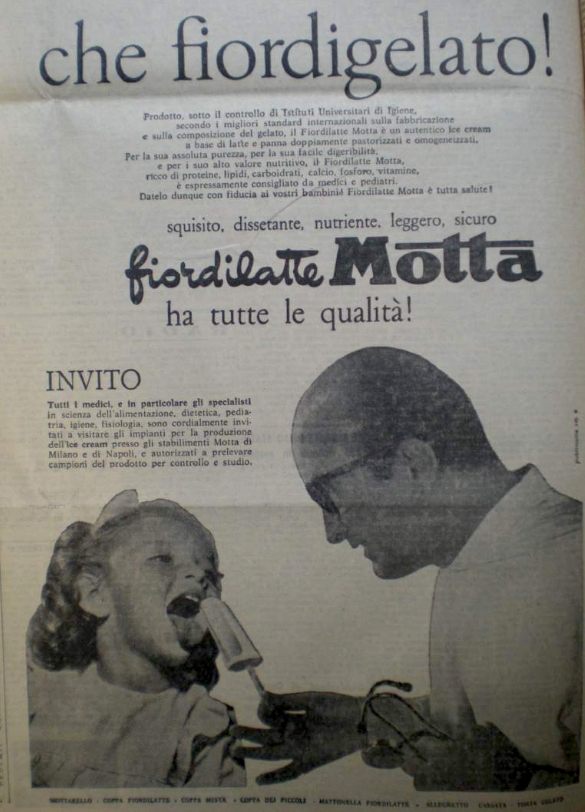

One way Motta did that was by featuring doctors, clad in white coats and stethoscopes, in their advertisements. Historian Maria Chiara Liguori, who analyzed this imagery for a 2015 article in the Advertising & Society Review, noted that “instead of focusing on the taste, they kept repeating how healthy it was. One such advertisement depicts a young girl getting a check-up. Her mouth is open, with her tongue out, and a pediatrician is offering her a gelato on a stick. The accompanying text invites all doctors to visit Motta’s ice cream production plants in Milan and Naples, and take samples with them to study. The not-so-subtle message? Industrial gelato is hygienic, even healthy—unlike what artisans produce.

Another advertisement even boasted that Motta gelato is more nutritious than chicken, fish, or eggs. In that case, Liguori believes it wasn’t a slight against artisanal gelato, but rather an appeal to poorer families. “It’s a comparison I saw in many products of the time: Don’t worry if you can’t buy meat. This is the same thing,” she says. Italians are well known for being unreceptive to change, particularly when it comes to food traditions, Liguori notes. But these techniques did the trick. Artisanal gelato sales plummeted, forcing many shops to close. Several generations of families lost their livelihood, too. “It was a national tragedy,” Polliotti says.

It could have been permanent, if it weren’t for the efforts of a few key defenders. One of those people was Angelo Grasso, the owner of a big gelato shop in the heart of Milan; Polliotti describes him as a visionary. After Grasso meet Carlo Alberto Ragazzi, Milan’s chief medical officer and an internationally renowned hygienist, at a seminar in 1953, the pair teamed up to save artisanal gelato. According to Polliotti, Ragazzi was persuaded to join the effort because “he realized that an entire economic category would have been unjustly swept away.”

Gelato makers soon convened in local, regional, and—eventually—national meetings, developing a united strategy to fight back. If the concern was that gelato wasn’t hygienic, they would make sure it was as safe as possible. So they launched professional courses for gelato-makers, in an effort to ensure that best practices were in place. They encouraged meetings with health officials, and demanded testing to prove that the public had nothing to fear from eating their gelato. As Polliotti notes, they even targeted the source of the bad press directly by creating a competition for journalists writing about the nutritional aspects of artisanal gelato. Gelato makers also wore lapel pins declaring their membership in the Committee for the Defense and Promotion of Artisan Gelato. To this day, the Carpigiani Gelato Museum has a display case filled with the 1950s- and 1960s-era pins, which depict images of cones and desserts.

The industry got a boost from rapidly-improving technology, too. Companies such as Carpigiani made machines that made it not only easier and faster to produce gelato, but also possible to introduce more safety controls. Their efforts not only resulted in recovering sales, but better gelato, too. Donata Panciera, a third-generation gelato maker whose family has operated shops in Italy and abroad, remembers just how important a reputation for cleanliness meant for their business. Her family installed the most up-to-date equipment available, and communicated that to customers. They kept busy, even during gelato’s darkest days. “We worked all the time,” says Panciera, reflecting on her childhood during the 1950s.

Although Vivoli wasn’t born until after the crisis had passed, it’s something she takes lessons from even today. She says her father told her all about collaborating with colleagues from other cities to explain to the public what artisanal gelato is, and what makes it special. This has remained all too relevant lately, because so many shops that claim to be serving the real deal are just churning out pre-prepared mixes. So it’s still up to her—and other gelato makers of her generation—to keep the abbondanza alive. “A fight once in a while,” Vivoli says, “It’s good.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook