The Heart-Racing Drama of Dissecting a Beached Whale

While on the job, the anatomist Dr. Joy Reidenberg has been escorted by police and scrutinized by nude sunbathers.

About 31 years ago, when Dr. Joy Reidenberg was a graduate student at Mount Sinai Graduate School of Biological Sciences, she climbed into a trailer, then on top of a stranded 11-foot-long pygmy sperm whale lying on its back, and “cut the midline of its throat to get past the blubber.” She parted the blubber and muscles of the 1,000-pound whale to the sides and located the hyoid bone, “which is a free-floating bone in the neck,” she says. Underneath this bone was the trophy she came to claim, the larynx, “which is a cartilaginous structure at the top of the trachea.”

She then “freed up the muscle connections that attach the larynx to the sternum and the hyoid bone.” She did the same to the tongue and walls of the pharynx. Reidenberg then cut the trachea a few inches below the larynx to release its link to the lungs. Lastly, she removed the larynx, with some attached trachea, and placed it into a plastic bag.

The night before, she had received a call from the Marine Mammal Stranding Network, now known as the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries’ Office of Protected Resources leads this effort to coordinate emergency responses to sick, injured, or dead marine mammals.

The network informed her about a stranded whale in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The specimen was headed to the Smithsonian at 9 a.m., where it would be defleshed in preparation for its bones to be added to the institution’s skeleton collection. But in the meantime it was hers to dissect. She’d just have to get to New Jersey—and quickly. Rental car agencies in New York City opened around 8 a.m. So, as soon as she got one, she drove 55 miles per hour down the highway. Time doesn’t stop for dead whales.

The Marine Mammal Stranding Network called Reidenberg because she was doing “a research project in comparative anatomy and had made an official request for anatomical specimens from dead stranded whales,” she says. In other words, she operated as an on-call dissector, ready to mobilize to the relevant beach.

There are many factors to consider once Reidenberg receives permission to dissect. Enough daylight to examine the specimen is one. Whale dissection is not an ideal night-time activity, but it can be done in the dark, with guts and all. Low tide and a potential storm are two other factors. It’s quite difficult working on a beached whale in knee-deep water while it’s raining. Will the whale lie belly up or down? Will there be construction equipment to move the heavy parts? Will it explode when opened due to gas build-up? These are the questions she grapples with. She could face all of these obstacles, some, or none at all. In the case of the Atlantic City sperm whale, there was one obstacle she didn’t factor in.

A police officer stopped her for speeding. Flustered, she stepped out of the vehicle in her white medical coat and complied with his instructions. He checked the back seat. “His face just turned ashen white, it was really weird,” says Reidenberg. A few moments before, she had heard on the radio that a body chopped to smithereens was discovered in plastic bags. Her rental car was filled with scalpels, hand knives, gloves, wood saws, and an array of gardening tools—equipment one would need to commit such butchery. The plastic bags in the back seat certainly did not help. She explained her situation and he decided to escort her to the stranded whale. Partly, just in case he was wrong.

The ensuing 30-minute whale dissection was one of the most important she’s ever conducted. “Before this, it was assumed that whales did not have vocal folds (the scientific name for vocal ‘cords’),” says Reidenberg. “After observing this whale, and also comparing with dissections of other specimens, we made a discovery: Whales did indeed have vocal folds after all. What had been written in the literature was simply wrong.”

The journey to this breakthrough whale dissection was a long and winding one. “When I was very young, I really enjoyed trying to figure out how things work and that includes living things,” she says. Her father took her fishing. While he read the newspaper, she fished. He agreed to drive her to the pier as long as she gutted all the fish—he was a bit squeamish. She spent hours looking at the gills and the innards. “I was just fascinated by what was on the inside. The big problem for my parents was keeping me away from death you’d find on the beach.”

During Reidenberg’s senior year in high school, she interned at a veterinarian office on weekends and she enjoyed the surgical work. It wasn’t until when she attended Cornell University’s College of Arts and Sciences that she grew disillusioned with the veterinary field. “The veterinarians were telling me that, well, you’ll learn all these wonderful fancy surgical procedures but you’re never going to get to use them because most people will just euthanize the animal,” she says. Reidenberg toyed with the idea of being a medical illustrator, but someone in the field told her there wasn’t much work in it. What field could marry art and surgery together?

When she met Dr. Howard Evans one summer, she found her answer. Then the Anatomy Department chairman at Cornell’s New York State College of Veterinary Medicine, Evans educated her about research in the anatomy field. “I’m a comparative anatomist,” he told her, which was the first time Reidenberg had heard of such a thing. He assigned her a research project over the summer to dissect toadfish and draw their anatomy for a fish dissection manual. After she graduated from Cornell University, she obtained her Ph.D. from Mount Sinai Graduate School of Biological Sciences and researched the comparative anatomy of the upper respiratory tract in mammals. Yet, what fascinated her throughout her evolutionary biology and anatomy studies were whales.

They had “completely different anatomy from anything else from land and they were stuck with evolutionary baggage of having to make sounds with air.” Whales breathe with their blowholes and hold that air in by closing their nostrils. Even with their nostrils closed, they can emit sound waves. It’s a pretty effective system that functions both for respiration and sound production, and to Reidenberg, that was simply incredible. There was much to learn about this evolutionary adaptation and what humans could learn by copying it.

Maybe we could have better underwater communications systems if we understand better how these animals communicate underwater,” she says. For example: “new protective devices that can be developed to prevent people from getting decompression sickness from diving,” or cure lung diseases.

Such research requires a deep dive into these giant beasts. The exact dissection process depends on the stranded whale, and can involve unexpected complications. She once dissected a whale on the nudity-friendly Cherry Grove beach of Fire Island, New York, a summer hotspot known for its LGBTQ nightlife, in front of over 5,000 people and the media. Dressed in a flowy dress and high heels, one news reporter “didn’t want to get near the whale because of course it smells terrible and the ground is full of blood and blubber and organs,” says Reidenberg. The cameraman and news reporter backed up to get a wider angle, but naked people filled the background. They argued over how close to get to the whale while avoiding showing bare bottoms in the shot. Eventually, they agreed the reporter would stand two feet from the whale carcass and put paper bags over her high heels so they could zoom in close on the whale. “I kept shaking my head and laughing,” says Reidenberg.

Even after she wrapped up for the night and drove back, “we had to navigate certain obstacles on the way out because some people had to decided they wanted to make love in the tire tracks we made coming to the whale dissection.”

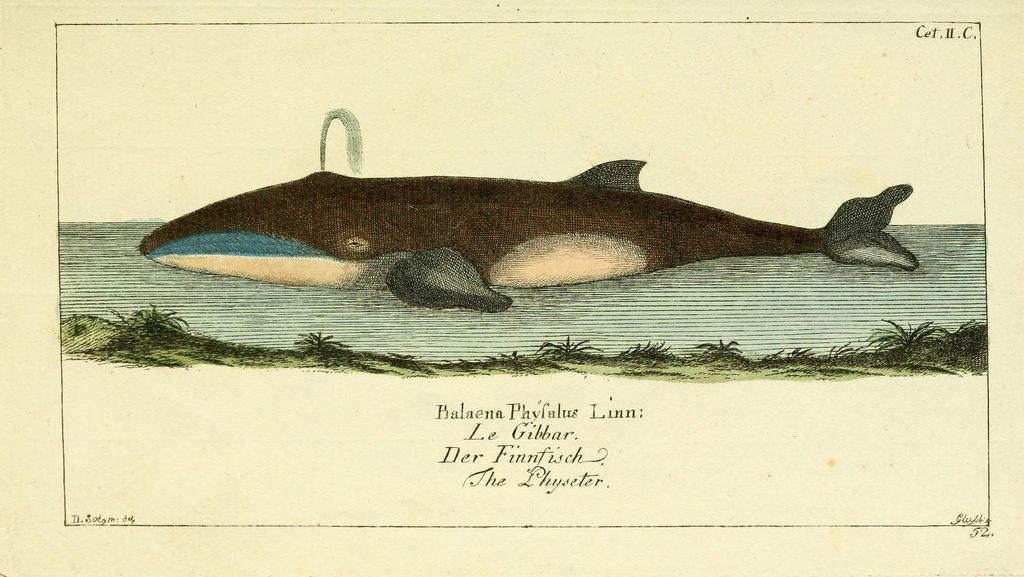

In 2009, Reidenberg dissected a fin whale off the southern coast of Ireland. According to the The New York Times, she had already dissected over 400 whales when she received a call to get on the next plane to Ireland. By the time she arrived, the whale was seriously bloated with bacterial gas. “It was inflating like the Hindenburg,” she told The New York Times. “If you cut in too deep, you end up with a million sausage links all over the place.”

She and the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group suited up in their protective gear and prepared their tool arsenal for the mission. She cut some holes into the whale’s throat to release the gas, which according to The New York Times produced “a symphony of flatulence” that took an hour to dissipate. Then, she took a meat hook to climb 10 feet on top of the fin whale and spliced rows of long cuts into its side. A hydraulic excavator from a local construction company unraveled the blubber strips. Reidenberg then started to pull out the whale’s intestines, dive into its cavernous abdominal cavity to extract more organs and bones, such as a pelvis and the sacred voice box, and placed these vestiges into a container. All of this carving took two days, lots of disinfection, approximately 15 showers, and a priceless amount of research.

At, 57, she’s still learning about these animals, but she wants to impart this knowledge to generations both old and young. “Science has to spend a certain amount of their time educating the public doing outreach education because otherwise the field is not appreciated by the public and it will die out if the public doesn’t know it,” says Reidenberg. “I find that if I want to reach the public best ways to do it is with the medium of television.” In addition to TV and TED Talks, she talks about science with classes of all ages and teaches at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the New York College of Podiatric Medicine. Through this outreach, she’s cultivated an avid following of budding scientists.

She can never predict when the next call for a stranded whale will come. It might come at 3 a.m. while she’s fast asleep or in the afternoon, in the middle of her Mount Sinai lectures. The “artist of anatomy,” as Reidenberg calls herself, is always prepared for a dissection.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook