How to Resurrect Gold-Rush Era Orchards Ravaged by Fire

The 2018 Carr Fire destroyed historic fruit trees—but not the will to make them bloom again.

On the afternoon of July 23, 2018, in the heart of Northern California’s Whiskeytown National Recreation Area, a vehicle towing a dual-axle trailer blew a tire. As the steel rim scraped the highway’s pavement, sparks flew into the dry grass lining the road and ignited what became the Carr Fire, the most destructive fire in National Park Service history. Over the next five weeks, the conflagration would tear through 97 percent of Whiskeytown’s 250,000 acres, incinerating almost everything in its path.

The fire leveled administration buildings and reduced park residences to piles of ash. Marinas, boats, and bridges were heavily damaged or destroyed. Thousands of trees were blackened and burnt, including many in the park’s historic fruit orchards, which were planted at the height of the California Gold Rush and had survived more than 150 years of fire, floods, and drought.

A few weeks after the fire was contained, Keith Park, a NPS horticulturist based in the San Francisco area, made the four-hour drive to Whiskeytown to see if the flames had spared any trees in those storied orchards. It was the second time in three years that Park had visited. In 2016, he collaborated with colleagues on an orchard management plan, meticulously cataloguing, photographing, and assessing Whiskeytown’s centuries-old fruit trees. Now, he was documenting their demise.

Park revisited as many trees as he could find from that 2016 inventory. In an Excel spreadsheet, he recorded notes on each one, cataloguing the fire’s wrath with grim efficiency. “Mostly dead,” “almost dead,” and “nearly dead,” he wrote again and again. Some lines read, simply, “burned down (gone).”

“It was shocking to see the destruction,” Park remembers today, some three years after wandering around the charred landscape. “It was definitely sobering.”

But buried among that bleak spreadsheet were glimmers of hope. One apple tree, for example, was “badly burned” but also “a little green.” On a few other trees, Park found “some green tips,” and “slight green shoots.”

The fresh growth was good news with an expiration date. Those damaged trees were unlikely to survive, but, if officials moved fast enough, they could use the green tips and shoots to grow new trees and replant the orchard, preserving not just the genetic identity of the landscape but also the history it represented.

In the middle of the 19th century, as hopeful prospectors surged into the newly discovered goldfields of California, entrepreneurs followed close behind, opening up hotels and restaurants to make their own fortune providing services to the miners. The tidal wave of ambition had sometimes horrific consequences: For centuries, the land around Whiskeytown was home to the Wintu people, many of whom were forcibly displaced or murdered by gold-mad newcomers.

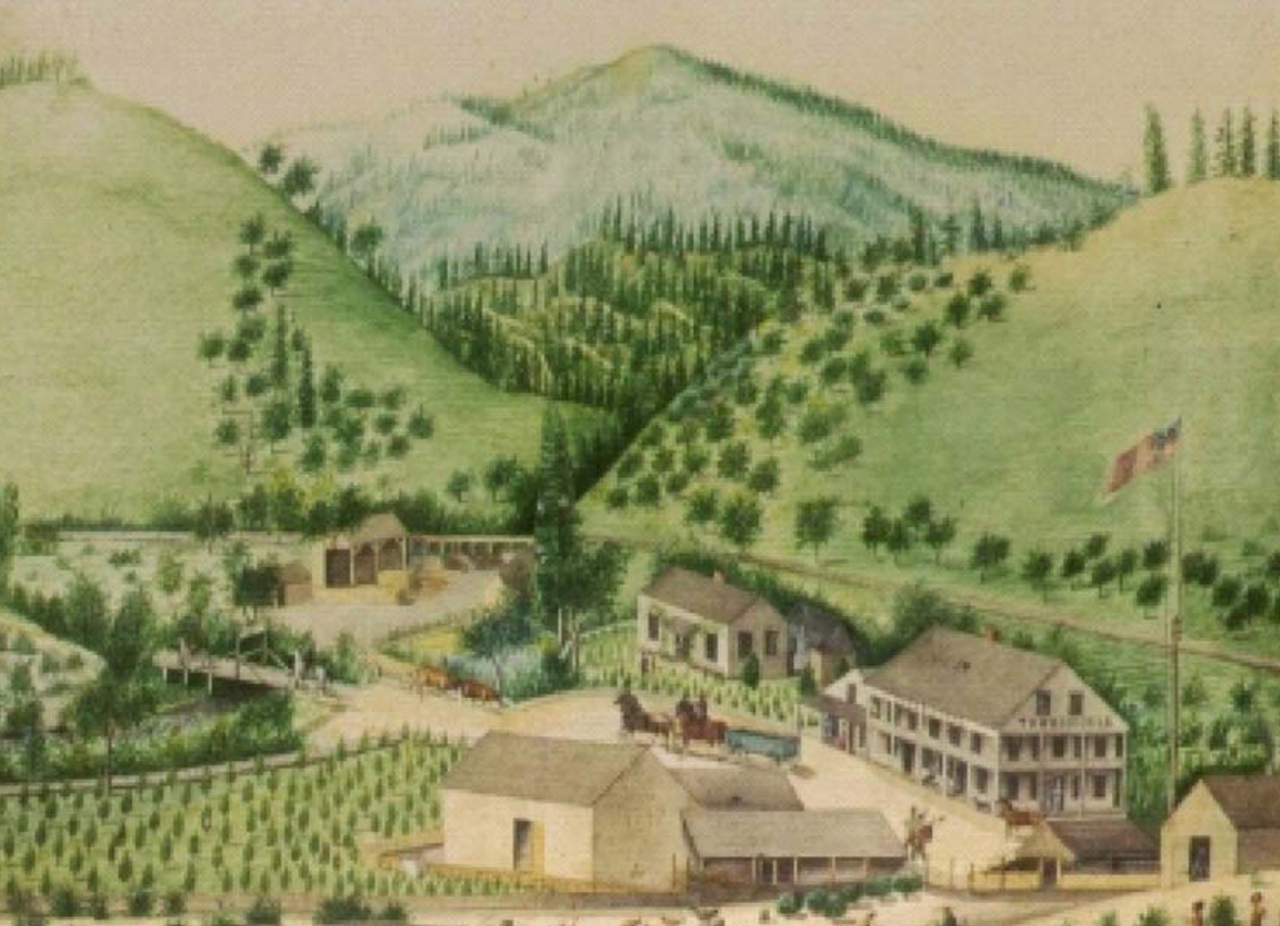

One of the entrepreneurs who sought to profit off the Gold Rush was Levi Tower. In 1851, with his best friend and brother-in-law Charles Camden, he bought land and a lodging house at the scenic confluence of three creeks in western Shasta County. There, Tower built a tertiary business, expanding the house into a 21-room hotel and planting gardens and orchards to feed his many guests. Apple, cherry, peach, pear, and nut trees grew quickly in the region’s fertile soil.

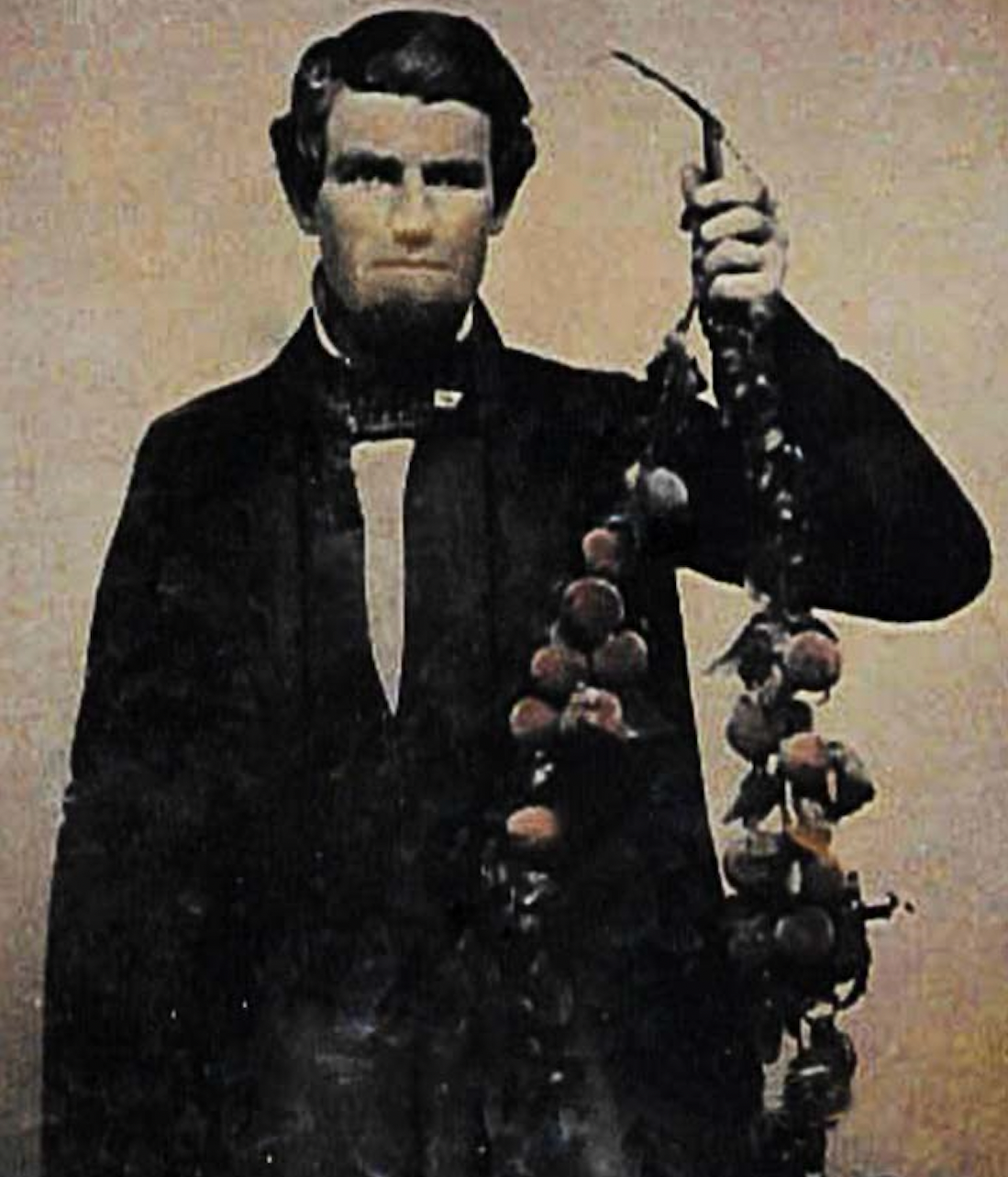

Orchards like his were sprouting all over the Sierra Nevada, providing food to Gold Rush boomtowns, but Tower’s soon became famous for its diverse and impressive bounty. Tower’s fruit trees arrived from every corner of the globe; they had sailed around Cape Horn or been hauled across the isthmus of Panama, decades before its canal was built. Others made the transcontinental journey aboard the wagon of Henderson Luelling, a celebrated horticulturist who introduced several new varieties of apples, pears, and other fruit to the Pacific Coast.

All of this careful sourcing paid off. In 1853, the Shasta Courier reported that Tower’s property was in a “high state of cultivation.” A year later, it described the orchard’s peaches as “rosy, luscious, and tempting.”

Situated between a number of productive goldfields, Tower’s hotel served a continuous flow of travelers during the height of the Gold Rush. Thanks to its lush orchards, manicured grounds, and decorative fountains, the property soon became less of a stopover and more of a destination in its own right. A guest in 1858 wrote in his journal that Tower’s orchards were the “finest in the state … loaded down with splendid-looking fruit.”

Levi Tower died of typhoid in 1865 and was buried among his celebrated fruit trees. For a few decades, Charles Camden maintained the grounds as conscientiously as his late business partner had. Twenty years after Tower’s death, a local circular reported that, “Bartlett pears weighing four pounds are no uncommon productions at this orchard.”

During the next century, however, age, neglect, and weather would take a toll on the orchards. As the land passed through generations of the Camden family, the fruit trees began to crack and wither. By 1969, when the NPS acquired the orchards as a part of Whiskeytown NRA, they had been reduced to a “smattering of remnant fruit and nut varieties,” according to an agency report. By the time Keith Park showed up in 2016, there were 167 trees left on 25 acres; 40 of them were deemed historic.

The orchards may have been small, but locally they held an outsized importance as “the oldest gathering spot in the county,” says Glendee Ane Osborne, cultural resource program manager at Whiskeytown. According to Osborne, up until the Carr Fire, the orchards were the site of picnics, family portraits, and even weddings. Every fall, people came to pick the fruit from the trees, which still produced one-of-a-kind varieties not found anywhere else. The smudges of green that Park found in the orchard in the month after the fire represented a chance to preserve that indelible part of Shasta County life, as well as its agricultural history.

But producing new trees from the live growth wouldn’t be simple or certain. Preserving the genetic identity (as well as the flavor and texture) of a particular variety requires a process called grafting—attaching the green wood of the old tree, called the scion, to rootstock, an established root system upon which the scion can grow. In order for grafting to be successful, the scion and rootstock must be compatible and carefully tended.

To take on this tedious, time-consuming project, officials at Whiskeytown turned to Tom Hart, co-founder of the Humboldt Cider Company in nearby Eureka, California. For the better part of a decade, Hart had been documenting the region’s homestead orchards. He had the knowledge and space needed to grow new fruit trees.

In the Spring of 2019, park employees delivered cuttings from 33 Whiskeytown trees to Hart’s growing plot in Eureka. “A lot of the branches were almost completely charred,” Hart remembers. Using the bits of green he could find, he grafted 90 new trees. Then he held his breath. About a month later, tiny buds began appearing on the scion wood. Altogether, 76 grafts were successful.

For the next two and a half years, Hart spent nearly every day with the trees, pruning, watering, and even serenading them. “I always played my Prince Pandora station,” he says. “so they were growing to some good tunes.” By last summer, the historic apple trees in Hart’s care were taller than he was. A few months later, the majority of the trees were ready to go home.

On November 19, park staff and community members gathered in Whiskeytown’s Tower Historic District—where the hillsides are still dark and denuded from the Carr fire’s wrath—and planted 51 apple trees in the Shasta County soil, more than a century and a half after Levi Tower had done the same. Tucked inside each tree was the genetic material of his famous Gold Rush orchard.

Park was on hand for the event—his work documenting the orchard before and after the fire played an integral role in restoring it as accurately as possible, down to how far apart the new trees were planted. “Under the circumstances, it was very satisfying,” he says. “If there was ever a happy ending to a sad story, this is it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook