In Northern California, the Time Is Ripe for a Forgotten Apple’s Comeback

Once-popular Gravensteins are available for just two weeks each August.

Each year in August, Gravenstein apples—a crisp and tart variety grown in Northern California—reach their ripest state. Their season comes earlier than most other apples’, and it lasts only a brief couple of weeks.

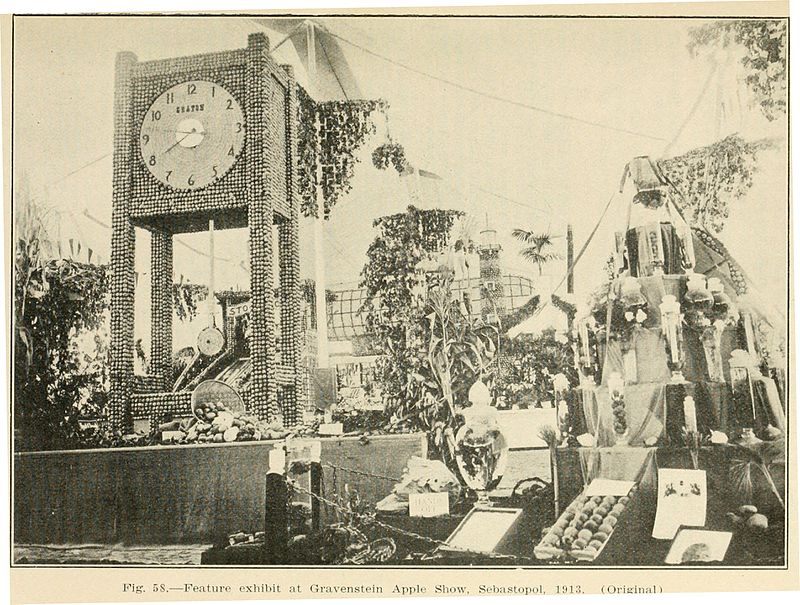

In the early 20th century, Gravenstein apples—identified by their skin’s rosy red-and-green gradient—were a popular, versatile breed that helped feed U.S. soldiers at war. But over the years, they became increasingly difficult to come by—and to learn about, as knowledge of their utilitarian nourishment faded.

Now, Gravenstein apple advocates in Sonoma County, inspired by the Slow Food movement, are working to resurrect the fruit’s unique cultural cachet and unmistakable flavor.

Gravensteins first arrived in Northern California in the 19th century and took root near Fort Ross, an important West Coast trading post for Russian trappers.* Over time, the west Sonoma County region—bifurcated by the aptly named Russian River—became known as a Gravenstein Eden. The climate there is a natural fit for apple orchards (and vineyards too). The local agricultural community, capitalizing on the ripeness of its land, soon made a business out of growing and selling the heirloom apple.

“During World War II, we had an industry here,” says Paula Shatkin, coordinator of Slow Food USA’s Sebastopol Gravenstein Apple Presidium. “[The Gravenstein] is a very versatile apple … people used to drive up here from all over the Bay Area during the summer season and take them home to can them for the winter. [They are] really good for making applesauce and juice, as well as baking.”

Thanks to that versatility, the Gravenstein became a popular and convenient snack for troops. In the 1940s, Sonoma County boasted 10,000 acres of Gravenstein trees, which kept the local farming community afloat. Today, only 960 of those acres remain, producing all 15,000 tons of crisp Gravensteins that appear in the U.S. each summer.

“The Gravenstein apple is an early apple—it’s the first apple [of the season to ripen],” says Shatkin. “And it doesn’t store well. More and more people, as the decades go by, buy apples like Red Delicious in the store … the Red Delicious has 41 percent of the American apple crop, [in part because] it stores well.”

Climate change has also played a role in the Gravenstein’s waning popularity. Since they reach peak ripeness earlier and earlier each year, Gravensteins “are competing with stone fruit, and they aren’t as sweet as a peach or a plum,” says Shatkin. Plus, consumers don’t eat as seasonally as they used to, and often buy the fruits in stores that have the most impressive shelf life.

Gravensteins are also up against neighboring Napa Valley grapes. Several Gravenstein orchards have been overtaken by vineyards backed by lucrative wine-production businesses. Slow Food USA’s Presidia—a global network of food-preservation campaigns, of which Sebastopol’s is just one—is working to protect the Gravenstein apple against this encroachment, in the name of biodiversity.

The Sebastopol Gravenstein Apple Presidium was successfully approved in 2003 by the Italian-based organization Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. It’s a campaign that local farmers and the Slow Food Russian River (the national organization’s local branch) have embarked on as a way to save the apples and preserve their rich cultural history in Sonoma County. (The first Gravenstein apple tree was planted here in 1811.)

With a Gravenstein Elementary School and a “Gravenstein Highway” (a stretch of California State Route 116), it’s safe to say that Western Sonoma County, at least, recognizes the Gravenstein’s history (and the significance of the area’s apple industry generally).

The team at Slow Food Russian River continues to keep the Gravenstein apple alive by collaborating with cider-makers who use the local apples in their recipes. Says Shatskin: “It’s another way to increase the market, and their viability.”

The Sebastopol community celebrates the Gravenstein’s cherished crispness every year by hosting the Gravenstein Apple Fair—a mecca for juices, pies, and sauces made from the apple. This year it’s happening on August 17 and 18.

* Correction: This article previously stated that Gravenstein apples were brought to America by Russian immigrants. The variety did not arrive on the West Coast until 1843, a year after Russian fur traders had left.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook