‘Extinct’ Apple Varieties Are Actually Everywhere

10 were discovered over just the last few months.

“I can see family resemblance in apples the same way you can in people,” says Shaun Shepherd, a botanist at the Temperate Orchard Conservancy outside Portland, Oregon. It’s that kind of familiarity with all of the fruit’s varieties, earned over a lifetime of study, that’s endowed Shepherd with the ability to bring apples back from the dead.

Figuratively speaking, of course. This week, the Temperate Orchard Conservancy (TOC), in partnership with the nonprofit Lost Apple Project, announced that 10 apple varieties previously thought extinct are, in fact, alive and crisp as ever. It was the richest season ever for the Lost Apple Project, which “seeks to identify and preserve heritage apple trees and orchards in the Inland Northwest,” according to the project’s Facebook page.*

To do that, a small number of volunteer apple foragers—a retired FBI agent among them—consult historical maps, records from 19th-century county fairs, newspapers, and sales ledgers to pinpoint former orchards dating back to the Homestead Act. If they’re lucky, they’ll arrive at these locations to find trees still producing fresh fruit—trees whose coordinates they carefully note before sending the apples off to TOC for analysis.

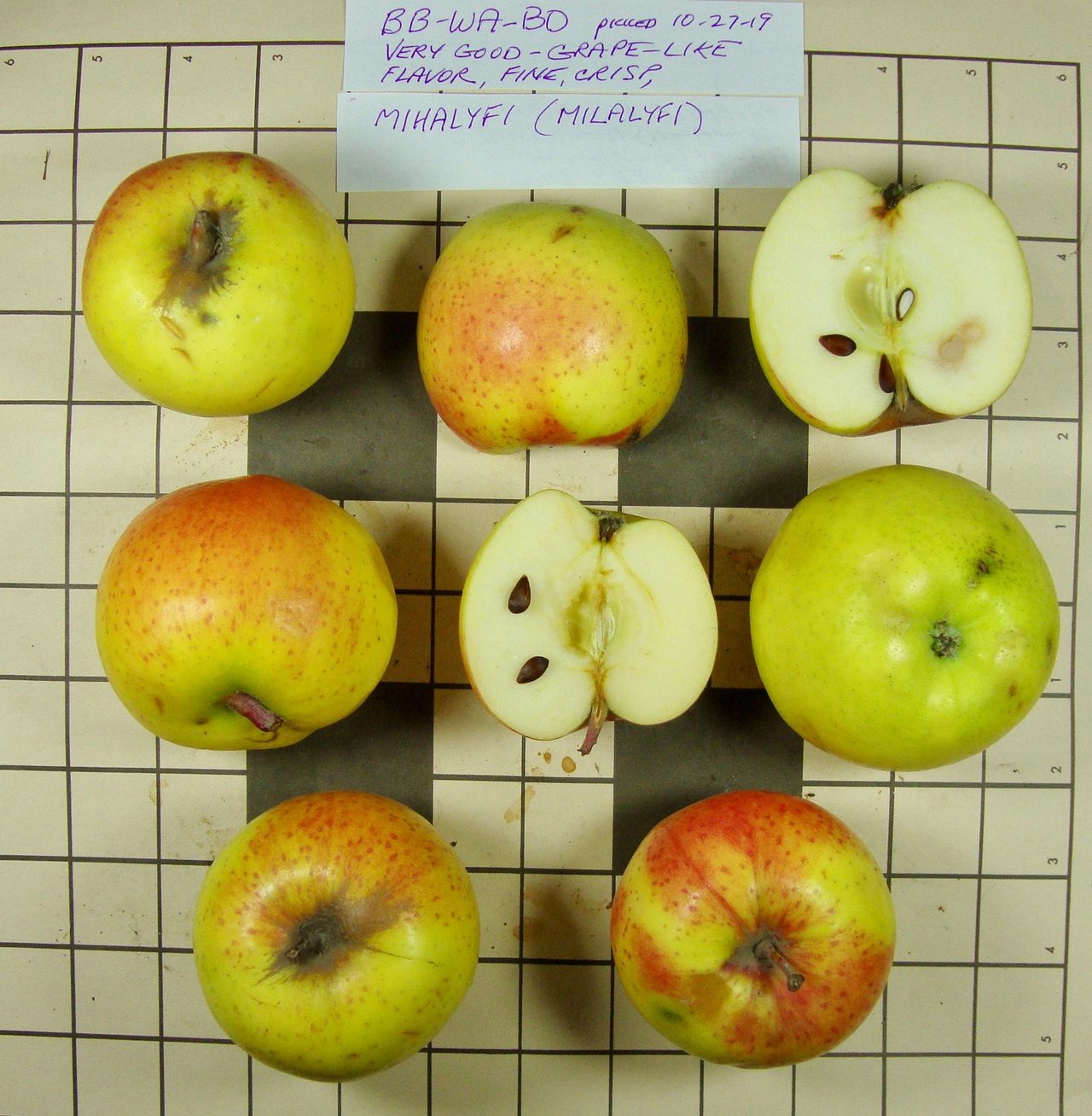

Once the apples arrive at TOC, Shepherd and his colleagues compare them against watercolor paintings commissioned by the United States Department of Agriculture in the 19th and early 20th centuries; they also rely on the descriptions in some canonical texts, such as The Apples of New York, published in 1905. Generally speaking, Shepherd says, the botanists at TOC don’t rely on DNA analysis because correctly identified samples are needed for comparison, and those are not available in most cases.

Shepherd, TOC’s Vice President and Pomologist, says some apples immediately stand out as different, while others are distinguished by far subtler features. They can range, on the one hand, from less than one inch to more than five inches across—a trait that can help the botanists quickly eliminate certain IDs and zero in on others. Other times, they’re splitting hairs over the lengths of stems, the textures of the skins, or—hardest of all—the different tastes. Apple flavor varies, of course, but only so much: “We ran across one several years ago that was minty,” says Shepherd, “which blew our minds.”

Shepherd is careful to concede that his conclusions may never be 100 percent certain, but he’s operating off much more than a cursory glance: This season, out of roughly 160 samples sent by the Lost Apple Project, he identified and thus revived the Gold Ridge apple by isolating “the depression around the calyx.” In fact, some of the 10 varieties recently rediscovered had been sent over by the Lost Apple Project several years earlier—it just took years of research to confidently identify them.

Though TOC will “look at the odd plum,” Shepherd says he focuses on apples for their variety, and the discoveries they invite. “There are old apple trees everywhere, and there are literally thousands of varieties that aren’t known to exist anymore,” he says. He believes that many of them still exist, and are just waiting to be found.

*Correction: This post previously stated that the Lost Apple Project is based in California’s Inland Empire region. It is in the Pacific Northwest’s Inland Northwest region, which is sometimes also referred to as the Inland Empire.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook