The Magnificent Orchards That Protect the World’s Fruit

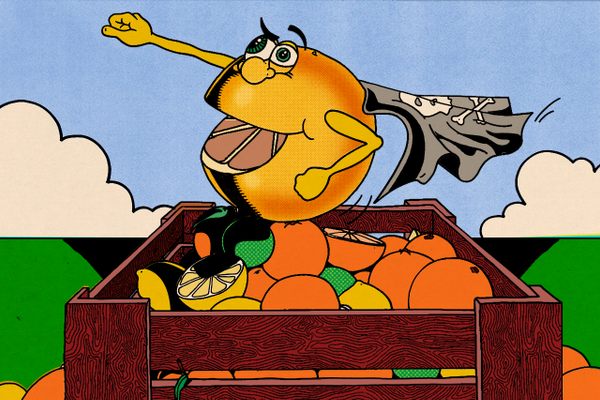

Thank these repositories for new and improved citrus, avocados, and more.

This article is adapted from the November 13, 2021, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Picking fruit at the University of California, Riverside, is a singular experience. In the Citrus Variety Collection’s orchard, researchers walk among trees bearing oranges, lemons, and limes of all shapes and sizes, from spindly to oblong, bumpy to smooth, huge to tiny. There are more than 1,000 kinds of citrus, two trees of each: a Noah’s Ark of citrus.

Riverside’s Citrus Variety Collection is one of the world’s many germplasm repositories, which are cousins to seed banks. Both safeguard the world’s variety of plants and crops. But unlike seed banks’ refrigerated warehouses, repositories are lively orchards and fields and greenhouses, dedicated to preserving living genetic material for research and grafting.

My dream trip would be a world tour of these agricultural arks. Visitors to the Citrus Variety Collection have described it as “sensory overload” to wander among blooming and fruit-covered trees of a thousand shapes, sizes, and scents. Repositories devoted to apples and avocados are also high on my list.

So far, I’ve yet to amble through any of them, since they’re not generally open for casual visits. The staff are always working on my behalf, though, by developing tastier fruits and nuts, combatting plant diseases, and, on occasion, letting the public in for tours.

Conversations With Curators

To learn more about germplasm repositories, I spoke in turn with Tracy Kahn, curator of the Givaudan Citrus Variety Collection in Riverside, California, and Malli Aradhya, a geneticist at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Tree Fruit, Nut Crops, and Grapes in Davis, California. Their answers have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Q: What are germplasm repositories and why are they important?

TK: When you look at the number of commercial varieties of citrus in the world, it’s fairly narrow on a genetic basis. So the collection preserves a diverse genetic base. To breeders, this is critical. If you’re trying to transfer in traits that are important, things like resistance or tolerance to [the devastating citrus disease] HLB, it’s really important that a germplasm has fruit with that trait.

MA: Plant germplasm repositories collect the genetic diversity of agricultural crops. We collect subtropical fruit and nut crop species from centers of diversity around the world and conserve them by growing them here, in the USDA’s 29 repositories.

Q: How are these repositories different from seed banks?

TK: It would be very difficult to maintain citrus seeds. Things like oranges or lemons are actually all ancient hybrids. Many have seeds that are not true to type. [Editor’s note: So any tree grown from seed wouldn’t be the same as its parents.] In citrus, you really need to preserve them as trees.

MA: We do store seeds. But nine of the 29 national repositories are for clonal crops, where you can’t store the seeds. The seeds are not viable for more than a year or two, and they don’t produce true-to-type progenies. So generally we preserve these as live trees and vines.

Q: I have heard the Citrus Variety Collection called the Ark of Citrus. Is that a name you ever use?

TK: Reporters have used that. It never came from me! It is one of the world’s most diverse collections of citrus and closely related species, and we do tend to have two trees for each citrus. But there are other germplasm collections in Italy, Corsica, Morocco, around the world.

Q: So it’s not all the animals, or citrus, in one raft? We have backups?

TK: That’s right. We’re not the only ones protecting citrus diversity.

Q: What do you do with the fruit and nuts from the repository trees? Do you snack on them at work? Take them home to make pie?

TK: I have to leave some citrus on the trees for research. We collect huge amounts of citrus for research projects. A small amount we sell. If you google “UCR citrus gifts,” you’ll see marmalades and olive oils. We make and sell citrus beers at the Barn on campus. We’ve sold to a few restaurants. Students and industry groups come through and eat some fruit.

MA: They’re all hugely valuable materials, so we generally distribute [the fruit] to plant breeders, researchers, sometimes nurseries. We have a mandate not only to freely distribute within the U.S., but around the world.

Q: What’s it like going into the fields during fruiting season?

TK: It’s not only fruiting season, but when the trees flower, that’s pretty amazing. The sights, smells, tastes—all this tremendous sensory material in one spot. It’s really great. The season is just starting to get going; the fruit is changing color from green to orange. It’s that anticipation of a new season.

Q: Is it possible for members of the public to visit?

TK: Usually it’s through a group—it gets complicated for individuals. We’ve held campus events [at UC Riverside] and held group tours.

MA: Yes, this is a taxpayer-funded collection [at the Davis National Germplasm Repository]. Anytime, anyone is welcome. But the best time is June, July, August. You just need to call and make an appointment and explain the purpose of your visit.

Fighting Off Plant Pandemics

Like many people, I got my first taste these past two years of pandemic life: tracking community spread, taking precautions such as masks, and rooting for vaccines.

But many growers and crop scientists have been fighting pandemics for years. (Although, as Dr. Kahn told me, researchers typically reserve the term “pandemic” for human diseases.) Citrus greening, or HLB, is a bacterial disease first documented in China that has devastated groves across the world. Panama disease led to the downfall of the Gros Michel, which was the banana shipped around the world until the 1950s. A new version of this fungus now threatens our banana supply once again.

The stakes are enormous, but just like with COVID-19, coordinated responses often prove elusive. In Italy, olive oil farmers refused to cut down trees to prevent the spread of a devastating blight, calling it a hoax or a conspiracy to free up land to sell to the mafia. In his book Banana, Dan Koeppel writes that plantation workers rarely change their shoes, which spreads contaminated soil, or sanitize tools used in infected areas.

This puts all the more pressure on the staff at germplasm repositories to find solutions. In the mid 1800s, French vineyards were nearly wiped out by an invasive aphid. French wine was saved by growing their grapes on rootstock from the Americas, which is immune to the insect. Similar solutions might be growing at these arks of citrus, avocados, and walnuts.

Browsing the Citrus Variety Collection

We can’t capture the sounds, smells, and experience of visiting one of these agricultural wonders. But we can share some of the varieties that make them so astonishing. Here’s a sampling from the Givaudan Citrus Variety Collection.

The sour Borneo Rangpur lime is valued for its hardy and resilient rootstock. Fruit expert David Karp also notes that it’s “delightfully aromatic and flavorful, and thus used to flavor gin.” It flowers beautifully too.

The Valentine pummelo hybrid was developed at UC Riverside and named for its resemblance to a heart and for its peak season, which is around Valentine’s Day. It has a sweet and floral flavor.

Native to Australia, the finger lime’s pearl-like contents, which pop when chewed, are nicknamed “citrus caviar.”

The unusually shaped Buddha’s Hand is more commonly grown in East Asia. This photo comes from nearby Phillips Farms, but the citron grows at Riverside as well.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook