Before Haunted Houses, There Were Hell Banquets

The macabre feasts have their roots in ancient Rome.

In March 1519, guests arrived at Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi’s home in Rome to attend the banker’s lavish Carnival feast. With the pious Lenten season coming up, this would be a day for excess. The attendees expected decadent spreads of wine, meat, and sweets, perhaps even a gorgeous sugar sculpture or two.

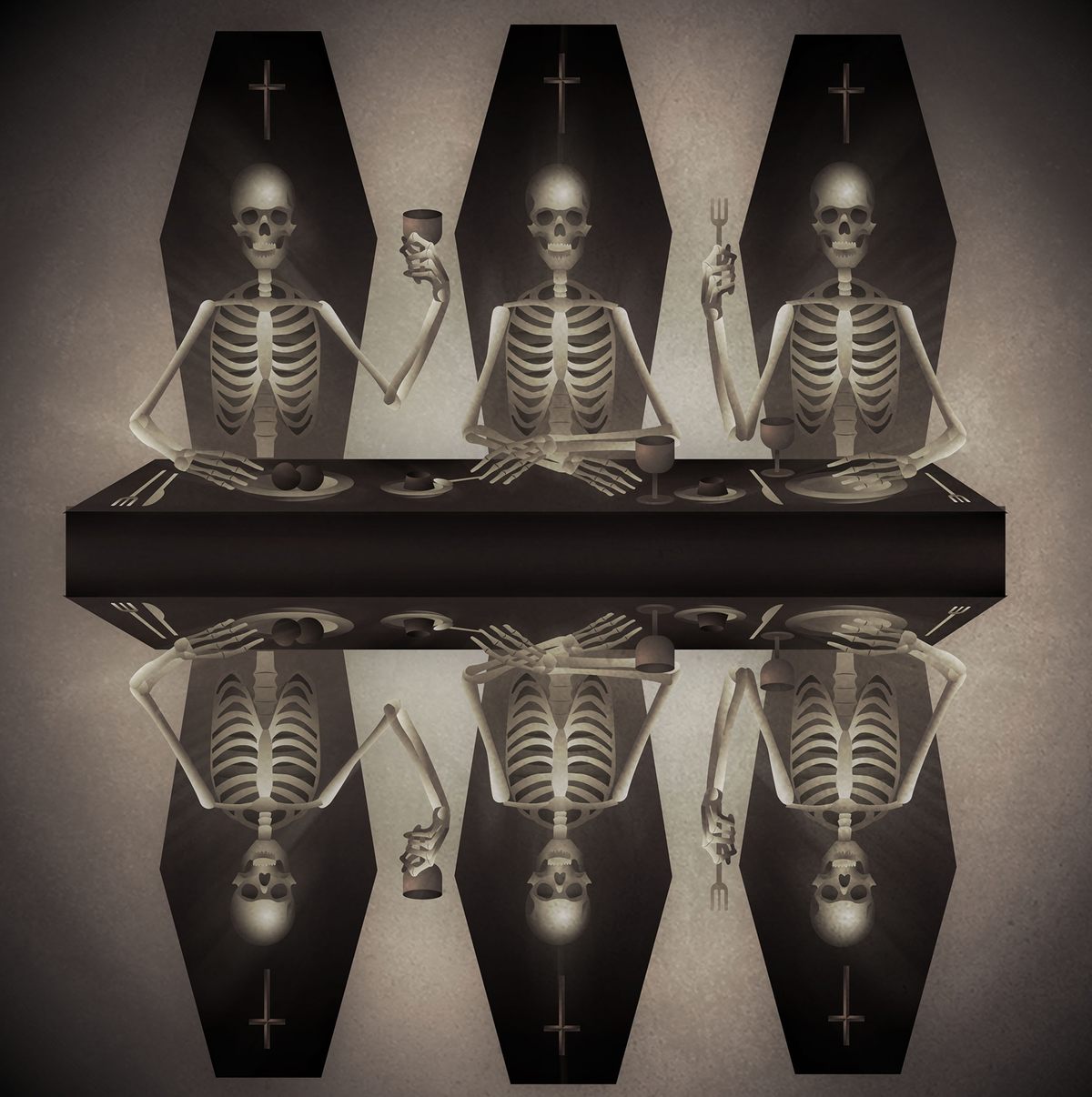

Instead, they were met with darkness. A single candle illuminated the entrance of Strozzi’s home. Confused, the guests moved up the stairs, through a black door, and found themselves in another dim room. The few flickering candles revealed skulls, skeletons, and a black table. Strozzi had set the table for a feast, but instead of roasts and pastry, the table held a giant skull surrounded by bones.

The frightened guests looked to their host for an explanation. “Gentlemen, eat,” Strozzi instructed instead. But, according to one account, “no one wanted to eat, because it was such a terrifying scene.” Just when his guests couldn’t take any more (at least two cardinals vomited that day), Strozzi orchestrated the grand finale, cracking open the skull and bones to reveal they were fake, and filled with roast pheasant and sausages.

The grotesque scene was met with mixed reviews. “It is said that such a wonderful supper had never been given in Rome and that it surely cost a great deal of money,” wrote one observer. “But, everyone was terrified tremendously.”

While Strozzi’s house of horrors might seem shocking, what’s even more surprising is that it was not the only banquet of its kind. The late historian Phyllis Pray Bober categorized these types of macabre feasts as “black or hell banquets,” where the settings were “designed to evoke funeral services at the least or afflictions of Hell itself at worst.” After tracing the history of such banquets, Bober identified examples stretching from ancient Rome all the way to 19th-century Paris. According to Bober, this family tree came from “the grandfather of them all,” a feast so horrifying that the guests believed they had attended only to be murdered.

In Roman History, written between 211 and 233, Dio Cassius describes a hellish meal hosted by Emperor Domitian around the year 89. The entire event seemed designed to torment its participants and delight the host. The banquet took place in a room that was completely black, from the floor to the ceiling to the table. The guests, most of whom were senators, were each assigned a seat with a personalized gravestone. Not only did the menu consist of food traditionally “offered at sacrifices to departed spirits,” but all the food was colored black. The senators were terrified. “Every single one of the guests feared and trembled and was kept in constant expectation of having his throat cut the next moment,” writes Cassius. Domitian apparently relished their terror, conversing “only upon topics relating to death and slaughter.”

However, Domitian’s banquet might not have actually happened. Dio Cassius wrote Roman History more than 100 years after the emperor’s reign, creating ample opportunity for inaccuracies or embellishment. Farrell Monaco, a culinary archaeologist who specializes in ancient Roman cuisine, has her doubts. “It’s hard to say if there was a literal banquet or not. The way Domitian was perceived by the senate and his authoritative nature opens the door for some pretty good satire,” she says. This portrayal would align with the sentiments of his contemporaries. Rome’s senate and aristocracy considered the emperor a cruel tyrant who ruthlessly eliminated his critics and insisted on being called “master and god.”

Monaco notes that if the story of Domitian’s dinner is satire, the all-black menu could have been a sly reference to the overuse of black pepper among elites. She points to Apicius’s De Re Coquinaria, an early Roman cookbook, which featured the luxurious Eastern spice in nearly all of its recipes. “Perhaps the term ‘black banquet’ was tongue-in-cheek, for an elite dinner and dining setting that used so much black pepper it rendered the plates, people, and walls black. This is the type of exaggeration you sometimes see in Roman satire pointed at the wealthy,” she says.

Whether or not Emperor Domitian’s death-themed dinner actually happened, it’s likely that Dio Cassius’s account inspired several memorable black banquets centuries later in the Renaissance. With the convergence of economic prosperity, intellectual curiosity (especially in terms of rediscovering ancient texts, including Roman History and De Re Coquinaria), and more than a little culinary show-boating, the Renaissance may have been the ideal incubator for such theatrically extravagant feasts.

Culinary historian Ken Albala calls events like Strozzi’s “competitive social banqueting,” a byproduct of Renaissance-era elites having “so much money, they didn’t know what to do with it.”

Hosts often stunned dinner guests with food or containers that came in deceptive shapes. “They were very fond of tricks and surprises and things that would confuse and delight you,” Albala says. Strozzi had his fake skull and bones filled with pheasant. Another 16th-century black banquet, hosted by a Florentine artist collective known as the Company of the Trowel, went even further. Their table appeared to be overrun by “repulsive creatures,” including serpents, lizards, scorpions, and spiders, but each was actually a vessel for meat, such as lark and thrush. Albala theorizes that Strozzi and the Company of the Trowel’s terrifying containers of food were probably made from sugar or marzipan formed with greased wooden molds shaped like bones, skulls, and creepy creatures.

There are no accounts from these hosts explaining why they felt compelled to hold such hellish feasts. Few of them seem to have been held in good faith, since the guests were not warned in advance about what they were about to experience. “Now what normally happens is you trick someone and they laugh,” Albala says. “But here the joke is not of a ‘haha’ kind. It’s the ‘let’s scare the pants off them and make them really nauseated’ kind.”

Some historians argue that black banquets like those organized by Strozzi and the Company of the Trowel may have actually been social commentary. Their themes of death, hell, and torture were powerfully subversive. Both the Company’s and Strozzi’s banquets took place in the 1510s, just after the Medicis had reclaimed power in Rome and Florence. Strozzi’s family was a rival to the Medicis and suffered financially under their rule. And it just so happened that several of the cardinals present at his terrifying banquet—and specifically the ones who were driven to vomiting—were themselves Medicis.

If Strozzi’s black banquet was a swipe at a rival family, it may have been sufficiently veiled to avoid retaliation. Not everyone was so lucky, or covert. Another anti-Medicean family threw a feast in 1519, mourning the “death” of liberty under their new rulers. The black-draped room displayed the Florentine coat of arms upside down, along with paintings of weeping women and the words “Liberty ground under foot” written on the wall. The host of this feast was later arrested, tortured, and imprisoned.

Perhaps that unfortunate nobleman should have followed the example of the Company of the Trowel, which formed in Florence in 1512. According to historian James O. Ward, the Company’s infernal feasts “were intended to encode a covert critique of Medici rule.” Whether or not this was the case is open to interpretation; the hellish banquet employed elaborate, cryptic storytelling: Guests first encountered an actor portraying Pluto, the god of the Underworld, who invited them inside to a feast celebrating his marriage to a captive bride.

After passing through a door designed to look like the sharp-toothed jaws of a serpent (which allegedly opened and closed around unlucky entrants), guests entered the Underworld: a dark dining hall covered in images of the damned being tortured. As a server dressed like the devil poured wine and dished out dinner on a shovel, guests dined on meat and ossi dei morti, cookies shaped to resemble bones.

On the surface, the Company of the Trowel’s banquet appears to be nothing more than an intricate haunted house providing dinner and a show. But Ward speculates that the Underworld theme was meant to suggest the punishment that awaited tyrants. Unfortunately, like Strozzi, there is no documentation outlining the Company’s intentions, leaving the true meaning of the meal a mystery.

There is little mystery, however, surrounding the last black banquet that Bober identified in her “family tree” of macabre feasts. Two centuries after the elaborate stagings of Strozzi and the Company of the Trowel, a French gourmand decided to throw a fake funeral feast. Perhaps the most eccentric of all black banquets, the 1812 event organized by Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière really doubled-down on the funeral theme. Receiving a funeral notice from Madam Grimod, guests attended believing that the event was actually a memorial service for her husband.

They arrived to find Grimod’s walls draped in black and a coffin illuminated by torches. As the attendees reminisced about their dearly departed friend, the doors to the dining room opened to reveal a lavish feast. At the head of the table Grimod, very much alive.

Scholars like Bober don’t ascribe any political commentary to Grimod’s feast and instead see his theatrics as distinctly personal. The fake funeral, for instance, was meant to determine who among his friends would actually show up to honor him. It wasn’t even the first time he hosted a loyalty-testing, morbid feast. Guests at an earlier banquet, in 1783, had to answer a series of questions about Grimod to gain entrance to the actual feast, where choir boys burned incense and coffins sat behind each chair. If any guest was disgusted by the display, he had no recourse. Grimod did not allow anyone to leave.

“His were not the imaginings of a cheerful and well-adjusted personality,” wrote Bober. Albala, on the other hand, is more blunt: “He was one sick fuck.”

After Grimod, Bober’s black banquet “family tree” stopped sprouting new branches. The death of the black banquet can be attributed to the decline of extravagant banquets overall. (Unless, that is, there are wealthy elite circles still holding death-themed feasts and keeping me, a mere pleb, completely unaware.) Eating habits have evolved since the age of opulent multi-course feasting, and death-themed dining has evolved as well. In the 1890s, several decades after Grimod hosted his funerary feast, Paris welcomed both a death-themed restaurant and a hell-themed restaurant. (They have since closed.)

If anything, macabre dining has become more egalitarian. In Des Moines, Iowa, a baker crafts “people pot pies” that evoke the gory faces of those who met violent ends. In Birmingham, England, a cake artist designs confections that resemble dissected corpses, bloody hearts, and other anatomical oddities. These thrillingly grotesque treats continue the black banquet’s tradition of culinary trickery, now no longer limited to the realms of the elite and available to anyone with an Etsy account.

To Albala, the thrill of eating morbidly themed food is timeless. “There’s a very, very fine line between titillation and disgust,” Albala says. “And there’s nothing weirder and scarier than putting something in your mouth that is really, truly disgusting.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook