Photographs Capture the Ancient Elegance of Horseshoe Crabs

“Nature is there for you, especially when you need it.”

The shores of Lewes, a small town on the Delaware coast, are a haven for horseshoe crabs. On a late summer morning a few years ago, Lynn Alleva Lilley was photographing the light dancing on the beach tide when she noticed a long, dark object pierce the glass-like water. The strange shape roused her from her meditative state. “Then the tail raised, and I realized it was a horseshoe crab swimming on its back,” Alleva Lilley said. “I had never seen that before. I thought maybe it was warming in the sun or was wounded. I just had to follow this creature. It felt like some benevolent force offered it as a gift and a lifeline.”

This curious encounter set the Maryland-based artist on a new mission to better understand these marine creatures. The horseshoe crab is not a crustacean, as its name might suggest, but an arthropod that has crawled on this planet for 450 million years. Its population is declining globally due to habitat destruction and overharvesting by the biomedical industry. (Horseshoe crab blood is used to detect infections.) During the summers of 2016 and 2019, Alleva Lilley followed and photographed horseshoe crabs as they ascended from watery depths to rest and spawn, sometimes by the thousands, along Delaware Bay.

Alleva Lilley’s photo book Deep Time, published by The Eriskay Connection, synthesizes the history, behavior, and unique anatomy of the horseshoe crab in lyrical, contemplative images. Her photographs show the slow, sustained routines of these creatures, as they embrace in mating rituals and burrow in sand, awaiting incoming tides. Atlas Obscura spoke with Alleva Lilley about finding beauty in the endless march of this compelling species.

How does Deep Time merge art and science?

As I began reading about the horseshoe crab, the scientific information became so inspiring. The fact that it has 10 eyes, two of which are sensitive to UV light emitted by the moon and stars to help it navigate at night, is so profound and poetic. It was a revelation and confirmation of the interconnectedness of everything.

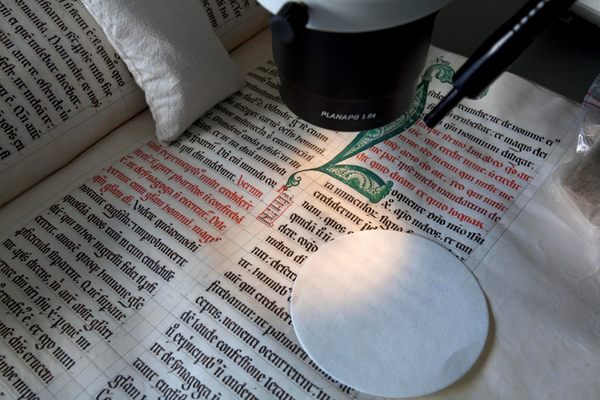

I wanted to learn more and signed up for a horseshoe crab workshop for educators, offered by the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve and the state of Delaware. Then, wanting to see what the embryos looked like, I met with scientists at the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment in Lewes. They offered me an artist’s residency within their lab and taught me how to use the different microscopes. It’s so different from the way I usually photograph. I also contacted the organizations that gather volunteers to count horseshoe crabs during spawning season, and was able to come along.

How did you know when and where to document the horseshoe crabs?

I researched the highest tides, the full and new moons, and the locations along the Delaware Bay and inlets. This meant that I would go out late to photograph the spawnings during the night high tides, and get up early to photograph the light and water during low tides. It was also weather-dependent. If the water was too cold, or if it was raining and waves were rough, there would be very few or no horseshoe crabs coming to shore to spawn.

In the end, I found myself photographing all the time and sleeping very little. There is so much that was surprising, like how the water color in different spawning locations made the horseshoe crabs look darker or lighter. Or how male horseshoe crabs would mistake my foot for a female and come up to it.

What’s it like to witness horseshoe crab spawnings?

You have no idea until you see it! It’s like clockwork when conditions are ideal. Especially at night, with the light from the moon, the atmosphere is magical. About 10 or so minutes before peak high tide, the horseshoe crabs start coming in, a few at first, and usually in pairs with the smaller male attached to the back of the larger female. Then more come in, until thousands have reached the shore with the help of the high tide and small waves. The females begin digging holes to deposit the eggs in the wet sand, and the males release the sperm in patches of foam.

There’s a moment when you realize that these creatures are doing what they’ve done for millions of years, and it has nothing to do with humans. We don’t control it—something else does.

“Deep time” originally referred to the vast time scale required to describe the geological age of theEarth. What does the term mean to you?

From an artist’s perspective, deep time involves the realization that everything is connected to everything. Decentering the human feels important. It takes hours, days, years. It’s hard to define intellectually what the time is. Maybe deep time is more of an experience.

How has this experience led to a deeper understanding of the world for you?

I realized that there are so many other worlds in this world. If we just slowed down and took the time to look, then we can experience what Rachel Carson describes as “the sense of wonder.” You then find yourself seeing deeply.

What do you hope readers take away from your project?

To know that nature is there for you, especially when you need it. Like art. If you are open, curious, and don’t try to control it, it will take you on an unimaginable journey. You will know that humans are nature—that we are not separate from animals, plants, trees, insects, or each other.

Have your adventures with the horseshoe crab come to an end?

I don’t think I will ever get tired of seeing the spawnings. This past winter on the beach, there were many broken pieces of horseshoe crab molts that the tides had brought to shore. Something about those scattered pieces was so poignant. Now I find myself just photographing these fragments. When I see one or two horseshoe crabs on the beach in Lewes, I talk to them, say hello, and ask them where they’ve been and what they’ve seen, what they know.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook