How Xerox Invented the Copier and Artists Pushed It To Its Limits

The Xerox machine was a piece of technology that seemed to come out of nowhere.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

In an era where paper is becoming less important than ever, it feels a bit bizarre at this point to go back in time just 35 years ago, when paper was perhaps having its greatest moment of all time.

We were just a few years from the desktop publishing revolution, which expanded the sheer amount of stuff one could put on a page. The ‘zine movement was perhaps at its peak during this time, proving an important way to democratize content for the average person.

And around this time, the copier company Xerox was perhaps at the height of its powers both culturally and within the business world as a whole. And it did it all with a heck of a lot of paper.

It makes sense that its namesake technology was so popular, because the invention, when it first came about, was truly groundbreaking.

It also seemingly came out of nowhere. in the book Copies in Seconds: How a Lone Inventor and an Unknown Company Created the Biggest Communication Breakthrough Since Gutenberg, Harold E. Clark, an early Xerox employee, noted the factors that made Chester Carlson’s invention of xerography—the process of dry photocopying that gave the company its name—so unique.

“Xerography had practically no foundation in previous scientific work. Chet put together a rather odd lot of phenomena, each of which was relatively obscure in itself and none of which had previously been related in anyone’s thinking,” Clark explained. “The result was the biggest thing in imaging since the coming of photography itself. Furthermore, he did it entirely without the help of a favorable scientific climate.”

The technique, which combined electrically-charged ink (or toner), a slight amount of heat, and a photographic process, helped to change the office environment forever. Attempting to explain this process isn’t easy—just try following along with Carlson’s patent—but the end result made everyone’s lives easier.

(One area that Xerox does not lay claim to on the invention front is the color photocopier. In 1968, 3M beat them to the punch, launching its Color-in-Color device that year. The product required specially-coated paper to allow for the printing of photos. Xerox came out with its own rendition, the Xerox 6500, in 1973, and unlike its workhorse copiers of the era, it could only print four pages a minute. The market for color copiers struggled until the ‘90s.)

Just to give you an idea of how groundbreaking that was, here are just a few examples of the ways that people copied stuff before photocopiers came about:

Carbon paper: Invented at the turn of the 19th century, the ink-and-pigment material made it easy to write on more than one sheet of paper at once, which was at one point useful. It’s still around, but in very limited uses—these days, people who attempt to buy carbon paper are mocked by confused millennials.

Hectographs: Gelatin, which is secretly made of meat, isn’t just a good dessert food; it’s actually a pretty effective medium for making copies. This process involves creating a solid blob of gelatin, writing on a sheet of paper using ink, transferring the ink directly onto the gelatin, and then transferring that same ink onto new sheets of paper by placing them on the gelatin. (Here’s a video in case you’re curious.) Because it’s low-tech and relatively easy to make, it’s still a pretty common crafting technique.

Mimeographs: This system, which had the honor of having been partially invented by Thomas Edison, was one of the most popular ways to make copies before the Xerox came along. Basically, a page of text would be set up as a stencil inside of a metal drum, and users would fill the machine up with ink, then basically turn the drum to put words on the page. The result looked really good, but the process was somewhat complicated, as you had to basically create stencils out of any document you wanted to copy.

Ditto machines: If you went to school in the ’70s or ’80s, you probably ran into paper copied using one of these devices, which often came in a purplish hue. The devices, also known as spirit duplicators, worked somewhat similarly to the spinning motion of the mimeograph, but with an added touch—alcohol. The end result didn’t use ink, but it did have quite the smell. This scene in Fast Times at Ridgemont High doesn’t make sense unless you’re aware of what a ditto machine is.

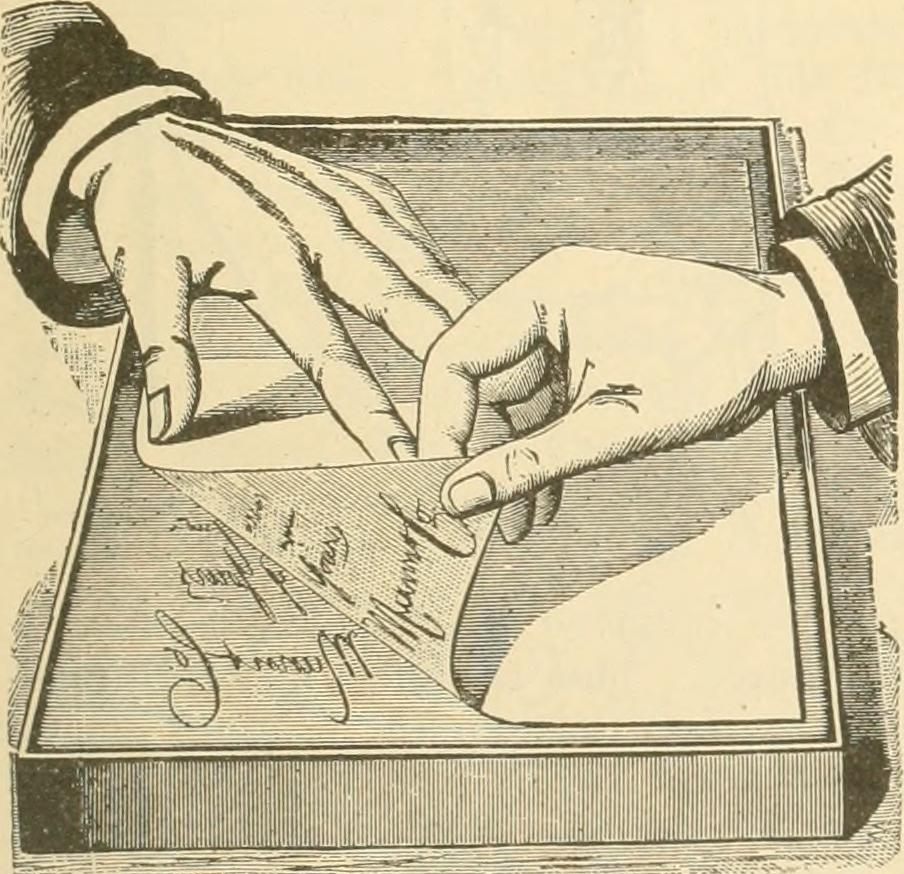

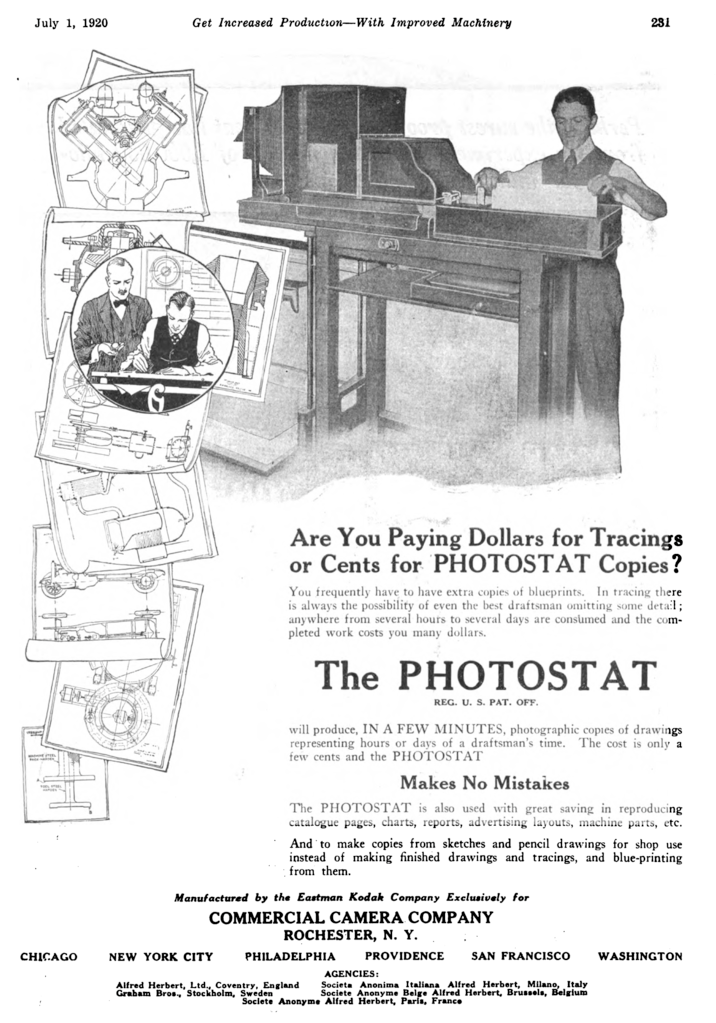

Photostat machines: Perhaps the closest thing to a modern Xerox machine, these machines relied on literally taking photographs of sheets of paper, creating negatives out of those sheets, then reprinting them. It basically combined the camera and darkroom into a single machine. The machines were large and the process relatively slow, but unlike some of the other processes listed, it wasn’t destructive: Once a single negative was created, an infinite number of copies could be made. Like Xerox, Photostat became so popular that the term was genericized. Rectigraph, one of the Photostat’s largest competitors, eventually formed the bones of the modern Xerox company.

It wasn’t just offices who loved photocopiers, either. Just ask Andy Warhol.

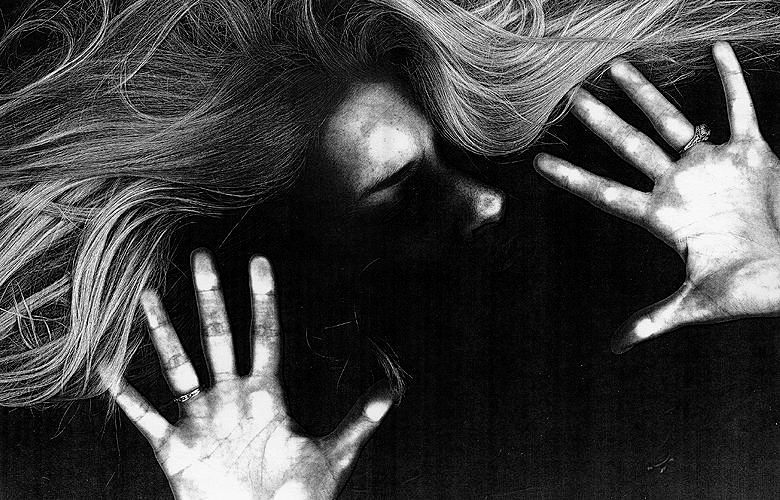

Warhol likely was the first person to think that putting his face onto a photocopier was a good idea. In 1969, the pop artist walked into the art-supply store at the School of Visual Arts in New York and saw an early Xerox-style photostat machine that printed to photographic paper.

He was friendly with the owner of the store, Donald Havenick, so he tried to convince Havenick to let him mess around with the machine. Havenick warned that the bulbs were hot, but that didn’t deter either Warhol or superstar Brigid Berlin, who also got in on the photocopying fun. That led to the self-portrait of Warhol above, which has been widely imitated by people screwing around with photocopiers ever since.

“Back in 1969, after showing the piece to my wife, she said it looked like death!” Havenick told Artnet of the work in 2012. “She thought it was just too morbid to hang in our apartment—until now.“

It was just one tool for Warhol, who had spent a lot of time perfecting his skills with related techniques like silkscreens, printmaking, and photography. But the fact that his first instinct upon seeing a photocopier was to shove his face into it highlights just how innovative the photocopier had the potential to become for the art world.

Within a few years of Warhol’s face finding a new self-portrait strategy, the zine movement helped crystalize the importance of photocopying as a form of creativity. Punk ‘zines like Sniffin’ Glue gained reach and influence thanks to copying machines, which made good stand-ins for Gutenberg presses.

Some zines made for particularly interesting art. Destroy All Monsters, a proto-punk band out of Ann Arbor, Michigan, built its early zines out of a wide variety of different copying techniques—from mimeographs to color Xerox copies. The band, which at one point included Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton, has remained fairly influential, but in recent years, it’s the band’s art that’s stood out, as both a subject of gallery showings and through a reprinted version of the band’s zine.

Part of the reason the band’s zine was so vibrant was because of the group’s proximity to the University of Michigan. That helped the band keep the costs down.

“Access to Xerox and mimeograph machines came through the school; some guy we knew worked in the art department and University of Michigan store. We could work all night and we didn’t have to pay,” Niagara, the band’s singer, explained in a 2011 interview.

Soon, Xeroxes would find their way to the hands of New York’s art scene. Before Jean-Michel Basquiat fully embraced painting, he was selling color Xeroxes of his artwork to Andy Warhol in the early ‘80s. Before Keith Haring embraced the world of his iconography, he was cutting up newspapers and creating his own shocking headlines, which he would then Xerox.

Perhaps the peak of what a Xerox machine could do came about in the early ’90s, when director and visual artist Chel White created an elaborate three-minute animated short out of heaps of photocopies, a few tinted pieces of plastic, and a lot of faces.

Like retro computers nowadays, the process of photocopying in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s carried an air of novelty in the art world, one that added possibilities rather than limits to what art could be.

Chester Carlson’s revolutionary approach to photocopying obviously had a lot more practical uses than simply printing zines—which is why you see them, or their competitors at least, in offices everywhere around the globe.

We expect to see them in movies and TV shows, too. And Xerox has tried to accommodate toward its legacy as necessary, donating vintage copiers to shows such as Mad Men. The company’s morgue is filled with old machines that tend to be put into movies and television as needed.

But perhaps the most interesting Xerox product to show up in a piece of entertainment wasn’t a copier, but a fax machine. In the 1968 Steve McQueen film Bullitt, there’s a scene in which a group of people stand tensely around a gigantic fax machine—a Xerox Telecopier, to be specific—waiting for it to do its job.

It’s ironic that the device is made by Xerox. See, a wait like that around a Photostat machine is what led Chester Carlson to invent something better.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook