Indigenous Artists Are Reclaiming Masks as a Source of Storytelling and Strength

Bringing together traditional materials and modern messages.

Many North American Indigenous cultures—from the Haida First Nations on Canada’s West Coast to the Hopi in the American Southwest—incorporate masks in their ceremonies, legends, and other cultural practices. So, confronted with the reality of the pandemic, in which masks have taken on a very different cultural and political significance, two Indigenous artists in Canada, Nathalie Bertin and Lisa Shepherd, decided to make them part of a global art practice. “Masks have really freaked some people out,” Bertin says. Art, they posit, is one way to confront to the negative ways that face coverings have been depicted in 2020.

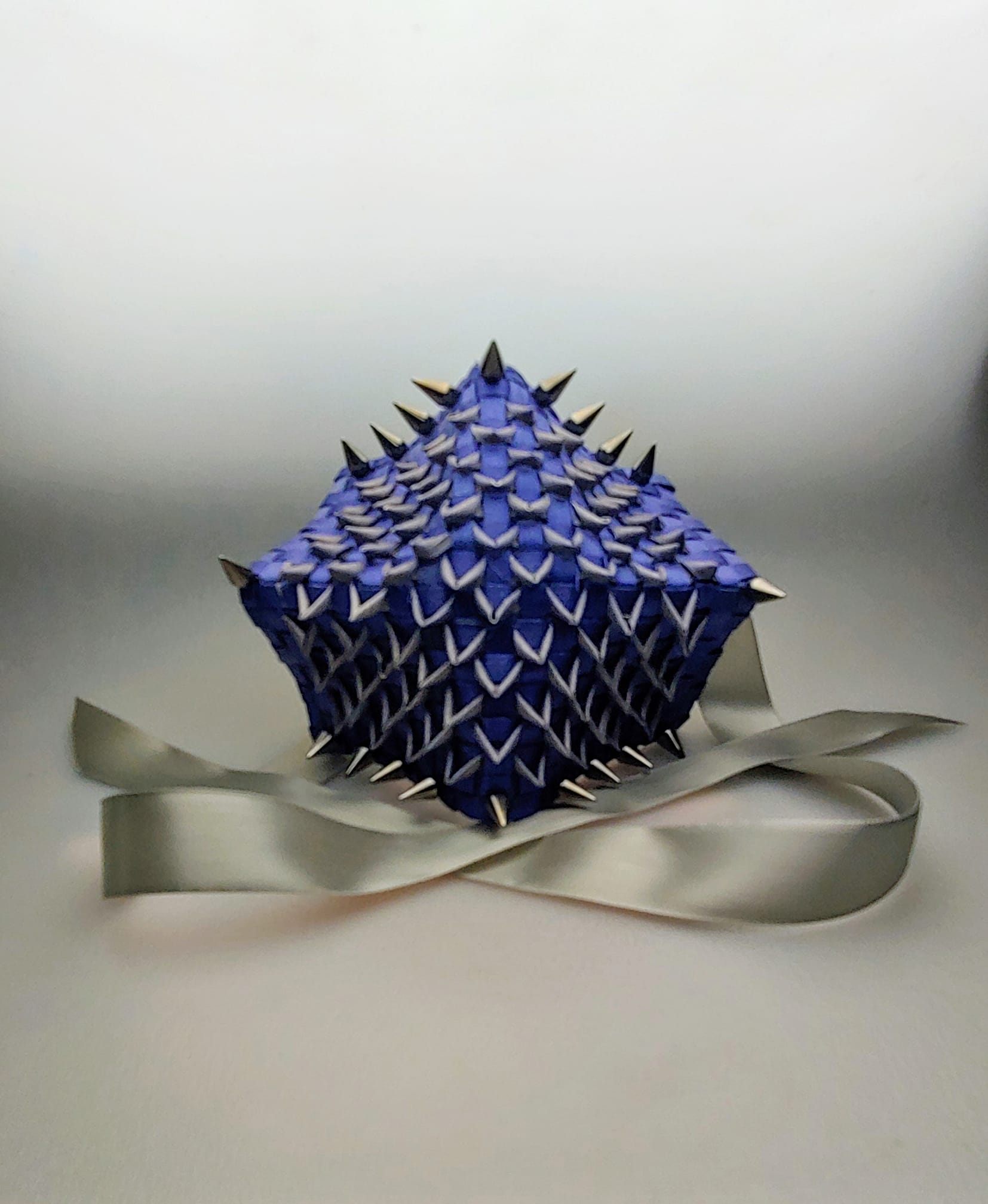

Bertin, who’s based in Ontario, and Shepherd, who lives in British Columbia, are both part of the multiancestral Métis group, and recently launched a project called “Breathe. A collection of traditionally crafted masks demonstrating resiliency through 21st-century pandemic.” They organized a Facebook group as a platform for artists, particularly those of Indigenous heritage, to share and display their own distinctive mask art.

In crafting masks for the Breathe. project, Shepherd explains that each artist is drawing elements from their own cultures, whether they come from Indigenous communities across Canada or the United States, or from as far away as Ireland, Australia, and Thailand. Several hundred masks are now displayed on the Breathe. Facebook site.

A number of the artists have incorporated beads, feathers, animal skins, and other traditional materials and imagery into their work. Towanna Miller-Johnson, who describes herself as Mohawk of Kahnawake from Quebec, crafted an elaborate black velveteen and felt mask and hat combination inspired by the crow.

At the center of the fur-trimmed mask that Colorado artist Heidi Kummli designed is a silver dragonfly. Melinda Schwakhofer, a U.S.-born artist of Muscogee (Creek) and Anglo-Austrian heritage, now living in the United Kingdom,used fabric based on an 18th-century engraving of a slave ship to create a mask on which she hand-painted the phrase, “I Can’t Breathe,” the last words of Eric Garner, who was killed by New York City police in 2014.

“Nathalie and I came from our Métis worldview,” Shepherd says, “but it was really important to us that we not limit the participants or the audience to Métis or Indigenous people. The virus has no borders.”

The Métis, one of the three distinct Indigenous groups that Canada officially recognizes (alongside First Nations and Iniut), have mixed European and Indigenous ancestry.

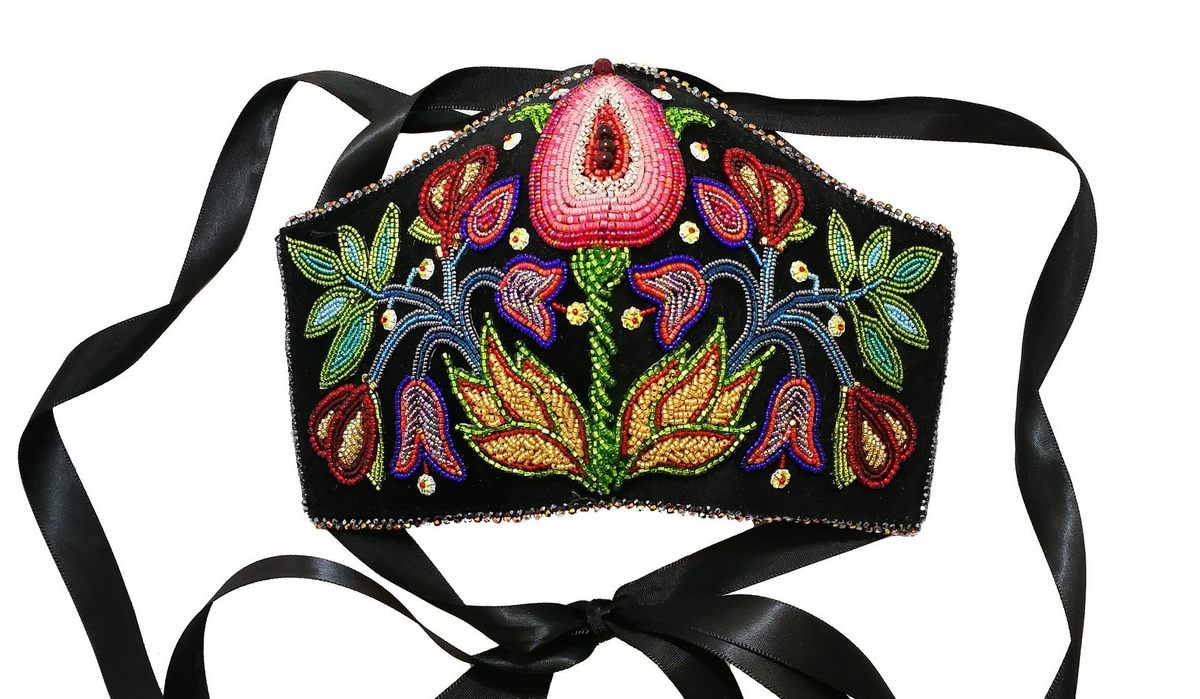

While masks are not historically part of Métis culture, Shepherd notes, beadwork is. “We have the nickname the ‘Flower Beadwork People,’” she explains. “Beadwork is one of the art forms that makes us distinct from other Indigenous people in Canada.”

In the 1800s, during the fur trade era, young Indigenous women learned embroidery and beading from nuns teaching in Canadian residential schools. The beadwork for which the Métis became known combined French-inspired floral embroidered patterns with Indigenous designs.

For Breathe., Shepherd created the beaded Honour Mask, trimmed with beaver fur, “to honor the people who have passed on to spirit,” she writes in her artist statement. “When we put on our masks, we are honoring all these lives.”

Bertin based the floral beadwork in her mask, Pandemic Vogue, on her own tattoos. She designed a mock advertisement, featuring a photo of herself wearing the mask, to explore the question of how wearing masks might become normalized, particularly for people of different cultures.

In the Breathe. project, Bertin says, the artists “are documenting artifacts from a specific period in human history.”

“It’s not unusual for us, for Métis people, to document things,” Shepherd adds, “to tell our story for the next generations.”

Though it started online, these stories are now moving into the real world, with the first Breathe. exhibition, including 45 masks, scheduled to open September 24, 2020, at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies in Banff, Alberta. A second Breathe. exhibit is slated to launch in spring 2021, at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario.

“If there’s one thing that history has taught me as a Métis woman, it’s that we need to be resilient,” Shepherd says. “When everything shut down, when people were feeling lonely and in need of connection, we created a community that uplifted artists,” providing a platform for crafting masks that expressed Indigenous traditions.

“This is true to how we do things culturally.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook