Israel’s Stalagmites Have Climate Stories to Tell

Formed by dripping water over thousands of years, the rocky formations point to ancient monsoons.

Long before the stalagmites sat on Ian Orland’s desk in Madison, Wisconsin, they jutted up from the floor the Soreq Cave in Israel’s Judean Hills, 18 miles west of Jerusalem. There, in the dripping darkness, the mounds of calcite were standing witness to the world outside.

When researchers want to learn about historic climates, they often go deep—down into Antarctic ice, for instance, or through the centers of centuries-old trees. They sometimes go into caves, too, because stalagmites and stalactites preserve clues to long-ago rainfall. Along with several collaborators from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Geological Survey of Israel, Orland, a geoscientist now at the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, recently studied a few of the lumpy rock formations from Soreq Cave to learn about the ancient climate of the Levant.

As rainwater trickles through cracks and into caves, it mingles with carbon dioxide and forms carbonic acid, and picks up dissolved limestone and dolomite along the way. As the carbon dioxide gas is released from the mineral-laden water, it forms a stony deposit called calcite, which collects on ceilings, walls, and floors. Over long, long periods of time, these trickles leave three-dimensional tracks—stalagmites and stalactites, which can take all sorts of flowing forms. The stone of these often-beautiful formations contains oxygen isotopes that can tell a lot about the water that formed them—where it originated, how long it traveled as vapor, and whether it came down in a light drizzle or a torrential downpour. Those chemical signals “are preserved in the stalagmite as it grows and are frozen in there forever, for all intents and purposes,” Orland says. “The amount of information contained within them is pretty remarkable.”

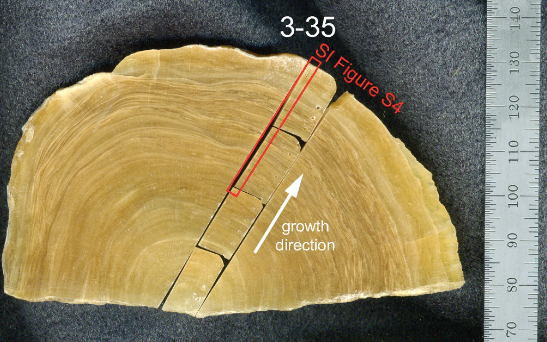

The stalagmites that Orland’s team studied had been collected a few decades ago by collaborators in Israel. They are just a few inches across, but they hold several thousand years’ worth of ancient data. One grew between 125,000 years ago and 115,000 years ago, and another between 115,000 thousand years ago and 105,000 years ago. (Stalactites hold climate data, too, but stalagmites are easier to study, Orland says. They always form like a pile of dirty laundry, with the oldest stuff down at the bottom.)

Today, Israel’s summers are “bone dry,” Orland says. But his collaborator, Feng He, a scientist at the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies Center for Climatic Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, had been working on historic climate models that suggest that, at the time the stalagmites formed, summers in the Levant were a lot wetter and marked by monsoon conditions that resemble winter rains, and today are seen much farther south. The model gave Orland, He, and their collaborators “a hypothesis we could test in the cave,” Orland says. If summer had indeed been wetter, Orland suspected, the team might find fewer seasonal ups and downs in the oxygen isotopes. Summer would have looked, chemically, like winter.

To study stalagmites, scientists cut them into slices, like the trunk of a tree, so they can see the rings or layers that built up over time. After the chunks were polished with a diamond-studded pad, Orland’s team analyzed the buffed bands for two oxygen isotopes: lighter oxygen-16, which today accumulates during the wet winter, and the heavier oxygen-18. As they describe in a recent paper in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they found what they thought they might: consistency. They saw proof of wetter summers, preserved in rock.

Orland’s team wonders if wetter summers may have emboldened people to migrate across the Levant. If so, there are likely many other clues to look for. “If monsoon rains really are reaching this area like we suggest, you would expect that there might be changes in the vegetation during that time period that might appear or be recorded in pollen records,” Orland says. He hopes that other researchers will find hints of soggy summer days in other records, and across the region. “Not necessarily more stalagmites.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook