It’s Not Just Tony the Tiger: Tijuana Bibles and the History of Cartoon Sex Icons

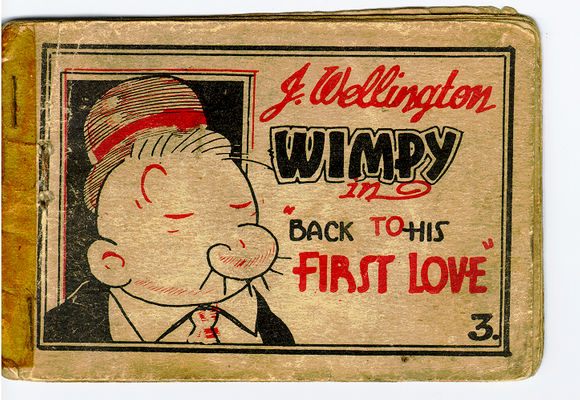

A Tijuana bible (Source: Wikimedia Commons/Anonymous author)

Note: Many of the links in this article contain sexually explicit material that is definitely NSFW.

This week, Twitter’s capacity for unfiltered interaction between celebrities, corporate brands, and the average—or not-so-average—human achieved a new milestone when Kellogg’s cereal mascot Tony the Tiger was forced to ask users to stop sending him sexually explicit fan-created images. Tony’s “fans” were so persistent that Kellogg’s ultimately resorted to blocking a number of users, giving Cheetoh’s Chester the Cheetah the perfect opportunity to dash in and pounce on any displaced fans of anthromorpohized cartoon animals.

The story sounds like an only-in-the-Internet-age event; however, erotic, fan-made illustrations of American celebrities, public figures, and—yes—cartoon characters existed well before Twitter and Tumblr.

Tijuana Bibles—also known as eight-pagers, Tillie-and-Mac books, and bluesies, among other names—first began appearing in the 1930s. These small printed pamphlets depicted famous newspaper comic characters, among other notable figures, in pornographic terms. The exact details of the publication process is somewhat mysterious, but academics such as Phillip Smith and Ellen Wright have found indications that they were printed by bootleggers, who had printing presses for making bottle labels, and initially sold in speakeasies. It’s generally accepted that between 700 and 1,000 comics were produced during the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s by a small number of anonymous artists. Dr. Donald Gilmore, who pioneered the study of Tijuana Bibles with his 1971, four-volume work Sex in Comics: A History of the Eight Pagers, asserted that the bulk of bibles were produced by 12 artists, whom he identified with names like “Mr. Prolific.”

In fact, many bible collectors conjecture that some popular mainstream comic artists and advertising illustrators such as Wesley Morse, the creator of Bazooka Joe moonlighted in eight-page smut.

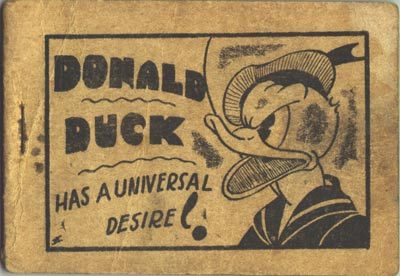

Bad Donald. (Photo: Tijuana-bibles.com)

And who were the subjects of Tijuana Bibles? Movie stars such as Cary Grant and Rita Hayworth, obviously—but also public figures like Joseph Stalin (a particularly memorable Communist sex romp is described here), comic strip characters such as Popeye and Dagwood, Disney characters, and advertising mascots like Bazooka Joe. The bibles’ disregard for copyright and libel laws undoubtedly played a major role in their notoriety (and appeal), with tabloids of the era describing movie stars “victimized by smut”. The subversion of comic strip and cartoon characters’ kid-friendly images also inspired the artists of the 1960s “underground comix” movement, including Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman. In one notable instance, a Tijuana Bible-inspired “Disneyland Memorial Orgy” was published in a 1967 issue of groundbreaking satire magazine The Realist in commemoration of Walt Disney’s death.

Today, Tijuana Bibles continue to be traded and analyzed by devoted collectors, some of whom share their finds on the web. Even university libraries maintain collections of Tijuana Bibles as important artifacts of illustration and Americana. And as Tony the Tiger is now well-aware, the practice of sexualizing cultural figures is far from a thing of the past, and rampant examples can be found anywhere fans gather online.

Interestingly, one of the closest present-day analogues to the Tijuana Bible trade can be found in Japan’s dōjinshi (self-published comics, often based on existing copyrighted works) industry. Only a small percentage of dōjinshi are sexually explicit works, but they sometimes represent the vast majority of fan-made work for an individual series, as these numbers from 2009 indicate. Although dōjinshi violate Japanese copyright law, it’s been theorized that the market ultimately benefits the larger manga (comics) industry in Japan and is therefore tacitly allowed. After this week’s events, it’s doubtful that Kellogg’s shares that sentiment, but we can be certain they’re now aware of Rule 34 at least.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook