A Portrait of James I’s ‘Husband’ Has Reappeared in Glasgow

“I desire only to live in this world for your sake,” the king wrote to him.

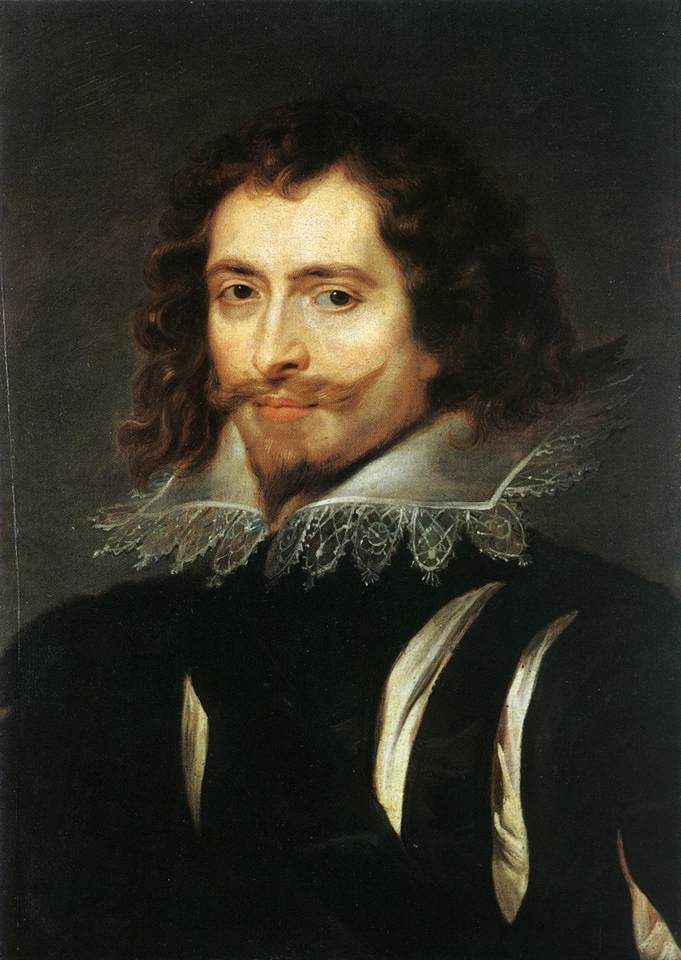

A lost portrait of the man whom English king James I referred to as his “husband,” “sweet heart,” and the one he loved “more than anyone else” has emerged from conservation work and been authenticated, after having been mistaken for a copy for centuries, the BBC reports. George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, rose to prominence in court after catching the king’s eye at a hunt. This 17th-century painting of him, now known to be by the Flemish great Peter Paul Rubens, had been concealed by layers of dirt, as well as later “improvements.”

The painting was spotted by Rubens expert, art dealer, and historian Bendor Grosvenor, while he visited Pollok House, a stately home in Scotland, with his wife and daughter. “It sounds rather silly to say it, but it was a bit of a eureka moment,” he told The Guardian. “I thought: ‘My god, that looks like a Rubens.’ This picture just seemed to shine out.” After a two-month investigation, he concluded that it is an original, though intended as a sketch for another portrait, which was destroyed in a fire in 1949. The unfinished work had been helpfully “tidied up” by another artist, Grosvenor said. “As a result, it began to look very stiff and more like a copy.”

In the painting, Villiers is depicted wearing an elaborate lace collar and a sash. He was known for his good looks, and had been described as “the handsomest-bodied man in all of England,” with a “lovely complexion.” James I lavished attention and care on him, and called him “Steenie” after St. Stephen, who was said to have had the face of an angel. However, whether Villiers and James I were lovers in the modern sense of the word has been a source of some contention. In their letters, James I states how he wept so profusely at their parting, “that I can scarcely see to write.” But scholars have argued that such sentiments are not atypical of male friendship in the 17th and 18th centuries. The rumors flared up upon the 2008 discovery of a secret passage in one of the king’s homes linking their bedchambers.

Whatever the true nature of their relationship, it all ended in tragedy. Three years after the king’s 1625 death, following a long illness, Villiers was stabbed in a pub in Portsmouth. His close relationships with James I and his successor, Charles I, made him deeply unpopular in court, and led to his assassination. Villiers is buried in Westminster Abbey, with the inscription on his tomb describing him as “the riddle of the world.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook