How Japanese Immigrants in the Amazon Created a New Cuisine

Native fish sashimi and green papaya pickles provided a taste of home.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of Japanese people sought opportunity abroad. Many ended up putting down roots in a tropical new home, and now, Brazil sports the largest Japanese population outside of Japan. By many estimates, the number of Brazilian citizens with Japanese ancestry currently clocks in at more than 1.5 million.

The highest concentration of nikkei, or people of Japanese ancestry, is in São Paulo. Many people of Japanese descent also live in Brazil’s south and southeast, where their forefathers came to work on coffee plantations more than a century ago. But a smaller number of Japanese immigrants also landed in Brazil’s north, settling in the state of Amazonas after the local government offered free land to those willing to farm it, starting in the 1930s. Surrounded by the Amazon rainforest and amidst temperatures that could reach highs of 95°F, Japanese immigrants needed to adapt to radically different surroundings. Part of that meant a new cuisine, featuring everything from bean sushi to sashimi made with native fish.

One researcher has taken it upon herself to research Amazonian-Japanese cuisine. Linda Midori Tsuji Nishikido, of the Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM), studied the eating habits of Japanese immigrants in the Amazon in the post-war period for her Master’s degree. Nishikido herself is nisei, or second-generation Japanese, and she interviewed her own parents, family members, and other Japanese immigrants for insight. Soon, she had reconstructed their adaptation process and documented their food creations.

The results were creative. Nishikido found that without the ingredients they had in their homeland, new immigrants ingeniously replicated traditional recipes from Japan’s rich gastronomic tradition, using local fish, native fruits, and even cassava, one of the starchy cornerstones of Brazilian cuisine. They couldn’t have had a richer pantry: After all, the Amazon rainforest is a wonderland of biodiversity.

But while the forest offered variety, Japanese immigrants found many of their old staples unavailable. Finding equivalents for soy sauce, miso, and tsukemono pickles in their new home proved difficult. According to Nishikido, many Japanese in Amazonas had no choice but to use local produce in familiar recipes. In the absence of soybeans, they recreated soy sauce using tucupi: a liquid extracted from bitter cassava that Brazilians in the north traditionally use as a seasoning. Plus, they engineered a miso recipe from native asparagus beans, owing to their similarity to more-familiar soybeans.

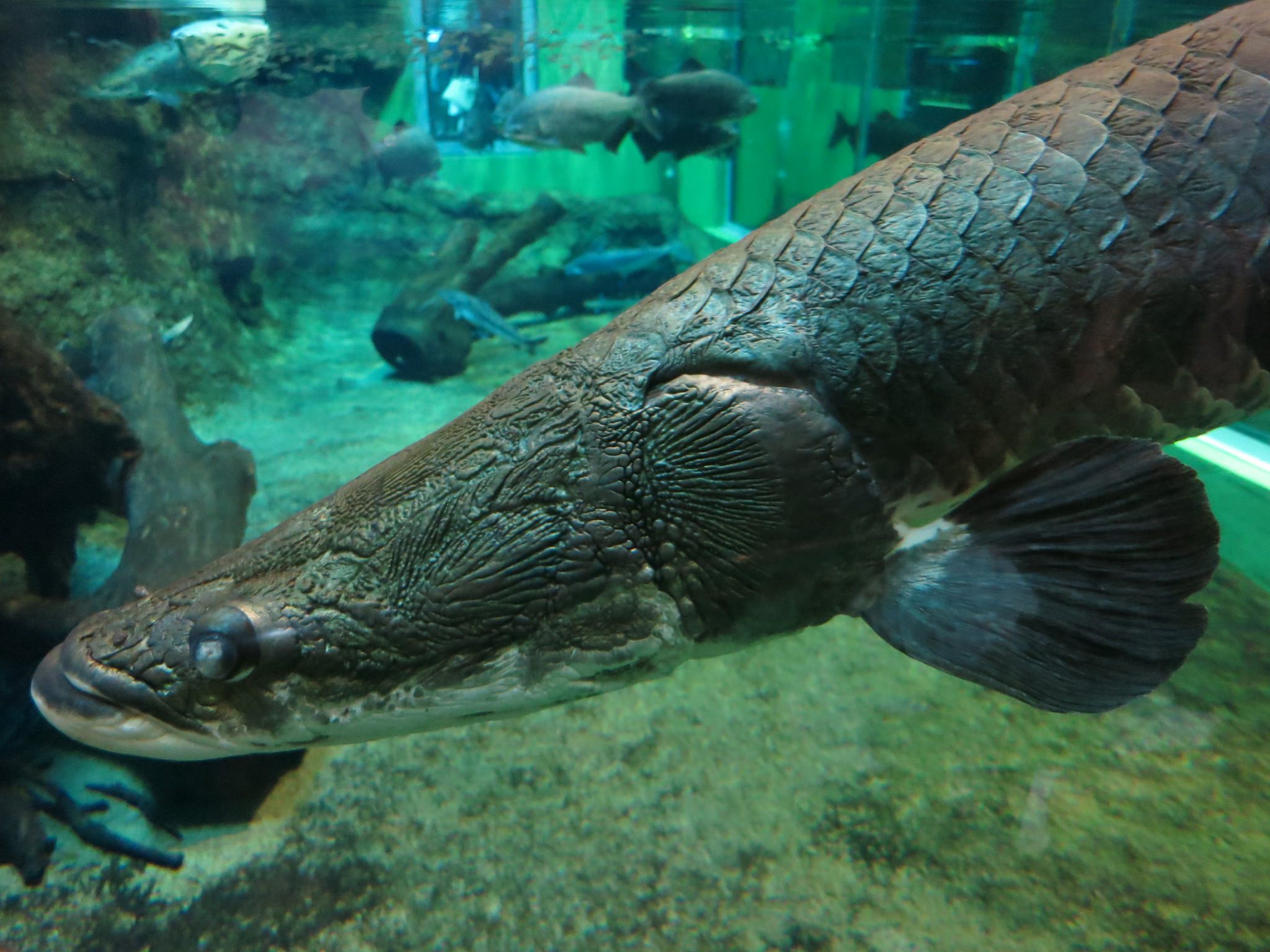

Recreating tsukemono pickles took even more creative leaps. Lacking radishes, turnips, and cucumbers, they pickled green papayas and overripe bananas. One thing that they did have in abundance was fish from the Amazon river. With many different river fish, they made sashimi and kamaboko, a type of fish cake made of pureed fish, cooked in a loaf-like shape and sliced for serving.

The immigrants also foraged the rainforest, looking for familiar ingredients such as edible mushrooms, fern buds, and palm hearts. “Over time, the table of Japanese immigrants became richer, because they learned to appreciate both the adapted cuisine and the local cuisine” of Amazonas, Nishikido says. After all, says Nishikido, food is far more than just a biological necessity. It is also a mirror on culture and society. To Nishikido, this hybrid cuisine reflects the emotions of a community doing their best to adapt to new surroundings. Replete in Amazonian-Japanese cuisine are “human feelings, such as unfamiliarity, homesickness, hope, [and] perseverance,” she says.

This type of food isn’t just eaten at home, either. Hiroya Takano arrived in Brazil with his family when he was 8 years old. Today, at age 66, he runs Shin Suzuran, a restaurant opened by his father in 1978. His journey from Japan was rooted in both disaster and opportunity. Originally from Wakkanai in the province of Hokkaido, his father was a farmer and manufacturer of potato starch until a strong, early frost devastated the region, leaving the family with few future prospects. So, his father decided to immigrate to Brazil, lured by the land concessions granted by the Amazonas government for farmers.

But the new farm wasn’t very successful, and his father instead opened a trailblazing restaurant. Shin Suzuran was the first Japanese restaurant in Manaus, Amazonas’s capital, and one of a few to focus on bringing together Japanese culinary tradition and local ingredients. There, Takano serves unique creations, such as vinegary sunomono made with water lily stems instead of the typical cucumber, fried nettle tempura and a lightly seared tataki made with tucunaré, or the indigenous peacock bass.

While the rivers offer many fishy treasures, it was an adjustment for Takano to move from chilly Wakkanai to one of the wettest places on earth. “When I got here, I was struck by the vastness of the rivers,” Takano says. “I had only seen so much water like this in the ocean.” He recalls his father gathering him and his siblings together and saying, “To stay here, you’ll need to learn how to swim.” Today, he has become familiar with the rivers, preferring to source local fish for the restaurant such as the peacock bass and pirarucu, an ancient, air-breathing, giant fish of the Amazon.

After the restaurant opened, the family recruited Japanese cooks from São Paulo to replicate traditional recipes. But one cook after another left Amazonas to return to the city. “Few adapted to life here, without other countrymen, without karaoke,” Takano says. In the 1980s, Takano started working as a kitchen assistant to learn the recipes himself and prepare them his own way: with lots of local ingredients. Today, his children also work in the restaurant. His eldest daughter, Adriana, studied nutrition and became a chef, responsible for the hot dishes. His son, Adriano, is in charge of sushi.

In a way, using local ingredients was a defense mechanism. “Japanese people have a great adaptive capacity. We are very determined,” says Takano. “When we arrived, Japan had lost the war, and the world was looking at us with different eyes. My dad then said we needed to learn to follow the laws and adapt to the country.”

Using local ingredients in recipes was his way of following his father’s advice. “We had to show that we valued and respected what the locals already had. The cuisine is Japanese, but the ingredients are Amazonian,” says Takano, who is now working on adding wild greens from the rainforest to the menu. One example of adaptation is his use of waterlily, a plant that has a huge cultural and symbolic value in the region but is not widely consumed as food in Brazil. However, water lily is an ingredient in cuisines across Asia.

Nikkei cuisine (often defined as Japanese-Peruvian food) is a current culinary trend around the world. But according to Nishikido, the cuisine developed by Japanese immigrants in the Amazon is unique, with its own ingredients and style. While much Amazonian-Japanese cuisine leans on Japanese technique, some old strictures have softened during the process of adaptation. For example, eating raw river fish such as jaraqui and tambaqui (ocean fish is the norm) has slowly become more accepted.

Nishikido believes that all the adaptations are highly innovative. New immigrants used local ingredients to mimic their original cuisine, and they succeeded in developing a distinctive new one. According to Nishikido, some ingredients are entirely intangible: the “emotions and longings,” of Japanese-Brazilians, she says, created a cuisine capable of helping them adapt to their new land.

Hiroya Takano couldn’t agree more.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook