The Japanese Ghost Town Buried Deep in a Canadian Forest

Archaeologists have dug up sake bottles and delicate rice bowls.

At first, it didn’t look like much: a clearing about an hour’s walk into the dense forest of British Columbia’s Seymour Valley, with some rusted cans scattered among the dank leaves and moldy tree trunks. It was 2004, and Bob Muckle, an archaeologist and anthropology instructor at Capilano University, was looking for a site to teach his students excavation. When a forester told him about the household artifacts locals had found in the clearing, Muckle assumed the area had been an early-1900s logging camp, one of the many small settlements that housed men who worked in the area’s timber industry.

But when the team started digging, they uncovered something unexpected: delicate, intact, blue-and-white china rice bowls whose undersides were stamped “Made in Japan.” Excavations quickly unearthed more objects—sake bottles, ceramics—suggesting the camp had been occupied not by transient loggers, but by a community of about 50 to 60 Japanese Canadians, including women and children, over a period of 20 years.

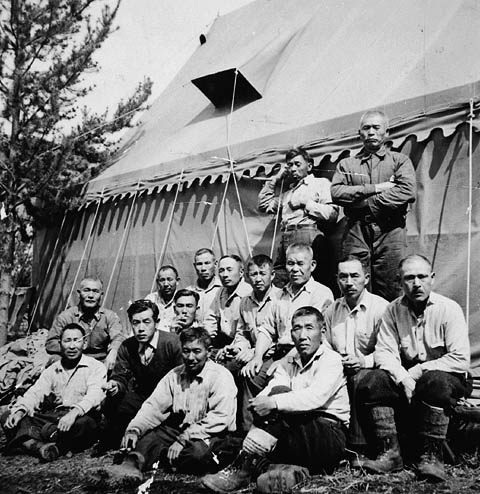

The people who lived here were likely employees of Eikichi Kagetsu, a prominent Japanese-Canadian logger. While the team has yet to uncover definitive proof of how long the village was inhabited, Muckle theorizes residents stayed from around 1920 to 1942, far after logging work dried up and other camps closed shop in the mid-1920s. In a woodsy nook an hour’s bus ride from Vancouver and another hour’s walk into the forest, residents built a small, self-reliant village. With racism against Japanese Canadians on the rise, says Muckle, the village’s remote location may have provided inhabitants with a sense of security. “They just could have stayed there on their own without being interfered with.”

Muckle’s team has been excavating ever since. The artifacts they uncovered reveal a community that maintained their cultural and culinary traditions, even in the middle of the woods. The team found delicate soup and rice bowls, likely bought in Vancouver’s Japanese neighborhoods after a laborious trek, which indicated that inhabitants still ate traditionally, probably with chopsticks. They uncovered a square of nitrogen-rich garden soil, fertilized with bone meal, which at one time may have been lush with Japanese vegetables such as daikon and fuki. Even rarer, the team found the remnants of a traditional Japanese-style bathhouse and shrine, suggesting an attempt at recreating traditional village life unparalleled in North America.

“It surprised me when I saw those artifacts. I thought ‘Oh! That’s pretty nice china!,’” says Linda Kawamoto Reid, reference archivist at Canada’s Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre. Indeed, the fine quality reveals that village inhabitants sought to make the remote space feel like home. But, says Muckle, they also carry a more sinister implication: that residents likely left in a hurry.

“Usually when people abandon a site, they take the good stuff with them,” says Muckle. But here, the good stuff was left behind: parts of a camera hidden by the bath house, an expensive cook stove stashed as though someone meant to come back to retrieve it. To Muckle, this suggests the village’s residents left the site by force—possibly in 1942, when, just as in the United States, the Canadian government began interning Japanese citizens and their Japanese-Canadian descendants.

While World War Two was the tipping point, racist sentiment had been building against Canada’s Japanese community for a long time. It was fueled, partly, by white Canadians’ resentment of Japanese Canadian’s growing economic power, including their agricultural success. The first Japanese immigrants reached British Columbia in 1877, and worked as laborers in agriculture, lumber mills, fisheries, railroads, and mines. Despite racist policies meant to prevent Japanese land ownership, Japanese communities thrived. Many families acquired land, which they often held collectively, started farms, and became pioneers in British Columbia’s berry industry. They used their earnings to build self-reliant communities centered around institutions such as Buddhist temples and Japanese-language schools.

This self-sufficiency extended to the community’s culinary life. Early Japanese immigrants in Canada, particularly male railroad workers, existed on meager, employer-supplied diets that mixed Japanese and Canadian elements, writes archaeologist Douglas Edward Ross in his dissertation on early Asian-Canadian food cultures. “Since bread was expensive and we couldn’t afford the same foods as whites, we ate dumpling soup for breakfast and supper,” said one railroad worker of life in the early 1900s.

As the community grew, so did their imprint on Canada’s culinary landscape. In each Japanese neighborhood, says Reid, “There would have been a tofu maker, absolutely. There would have been somebody making miso.” Local communities likely milled their own rice. Japanese neighborhoods in cities such as Vancouver also supplied sake and tableware imported from Japan, including, Muckle speculates, some of the bowls and bottles at the Seymour Valley site.

Internment ruptured this thriving community. On February 24, 1942, several years after Canada’s entrance into World War Two, the federal Cabinet issued an order enabling the detention of “any and all persons” from areas deemed sensitive.* These broad powers were used to target Japanese communities. By March 16, Canadian officials transported the first group of Japanese Canadians to Hastings Park, a race track and exhibition ground in Vancouver. Officials housed women and children in barns. Those who resisted were sent to prisoner of war camps.

Interned Japanese Canadians—including, evidence suggests, those villagers from the Seymour Valley—were forced to leave almost everything behind. “They were only able to take one suitcase, anything that they could carry,” says Muckle. The Canadian government took the rest. Originally claiming they’d keep Japanese Canadians’ confiscated land in “protective custody,” the province of British Columbia encouraged the Canadian government to sell the property instead, using the proceeds to run internment camps.**

“They talked the federal government into confiscating the property and selling it off so that internees could pay for their own internment,” says Reid. “It’s just highway robbery.” Many Japanese Canadians—those who weren’t forced to work on road crews—were made to labor on sugar beet farms.

The trauma and displacement of internment caused many Japanese Canadians to lose track of their family histories. Another means of erasure, says Reid, was shame. Humiliated by racist treatment, many survivors preferred not to talk about that time. “There was this code of silence,” Reid says.

But in a clearing deep in the Seymour Valley, objects speak. In the years since they discovered the site, Muckle and his team have uncovered hundreds of objects, each holding stories of a lost way of life: A key to a home that has disappeared. A stopwatch that ceased telling time years ago. Milk bottles for babies that have long since grown. Stacked in the shadows of monumental, lichen-dusted trees, the blue-and-white rice bowls look ghostly, minute and delicate. Their presence is a poignant reminder of the communities broken up by racist government policies.

For Reid, these remnants of culinary life are also testimonies to Japanese Canadians’ strength. The Seymour Valley village, which the British Columbia government has commemorated for its significance to Japanese-Canadian history, is one of many archaeological sites whose objects reveal hidden memories. Among these sites are the fields of Tashme, the largest Canadian internment camp, which are now open for occasional tours. At a recent tour of the site, Reid says, the curator showed visitors a field where, after more than 70 years, the lush green leaves of fuki, planted by internees, continue to reach toward the sun.

“You’d have to survey people to see what would be the one thing, the one piece of food or vegetable that would signify the Japanese-Canadian spirit,” says Reid. “It might be fuki. Because it’s still growing.”

*Update 9/25/19: This post has been updated to clarify that Canada entered World War II in 1939, not in 1942.

**Correction: A previous version of this article stated that British Columbia is a state. It’s a province.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook