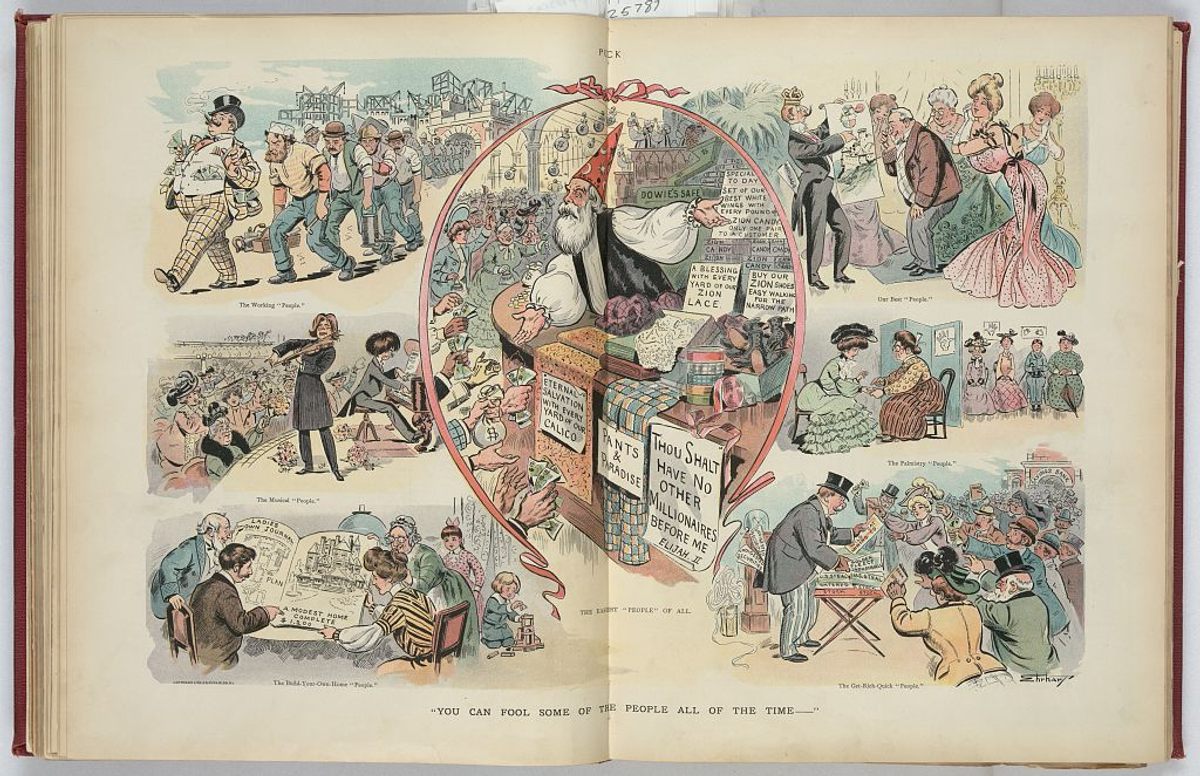

The Sketchy Faith Healer Who Tried to Save New York From Vice

John Alexander Dowie also established his own utopia just outside Chicago.

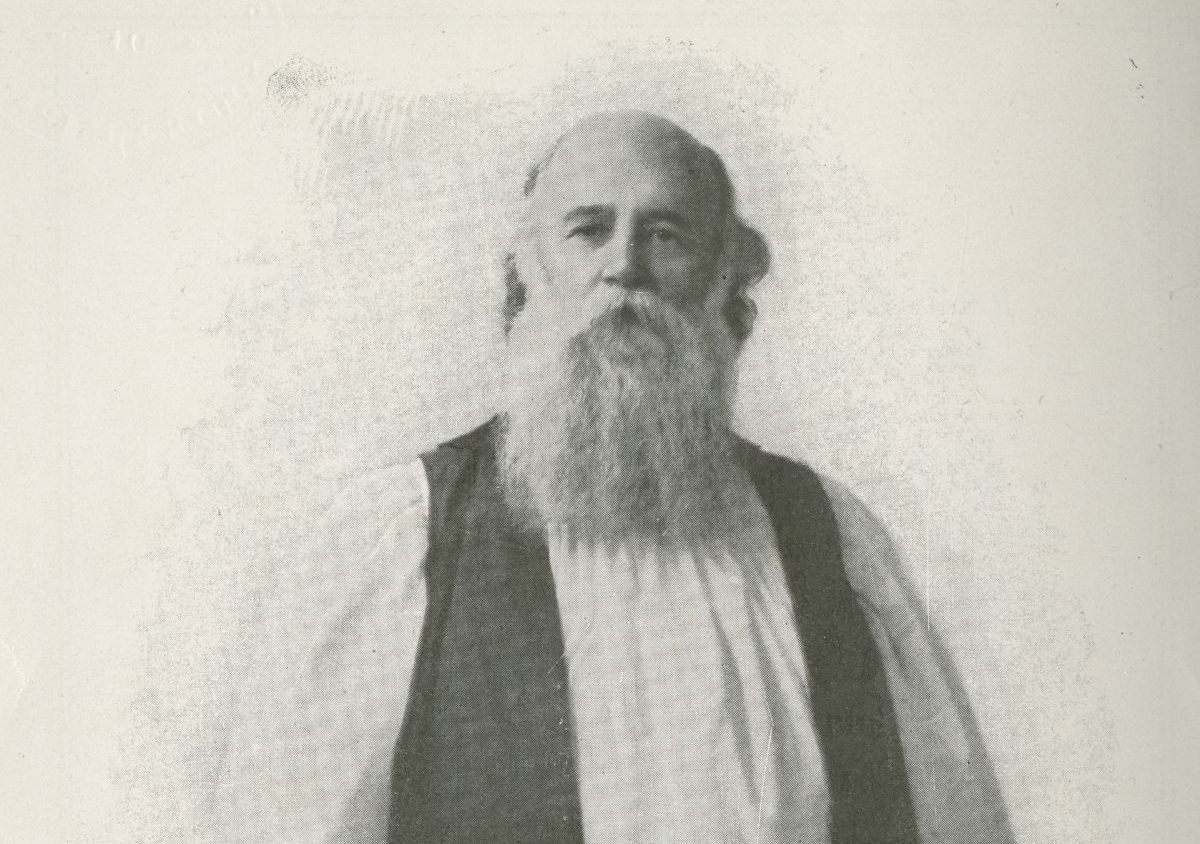

John Alexander Dowie was not America’s first faith healer—but he was the first to get rich doing it. Dowie, a Congregational minister originally from Scotland, discovered his unusual gift in 1876, when he was 29. A small girl dying of diphtheria was miraculously cured after Dowie prayed at her bedside.

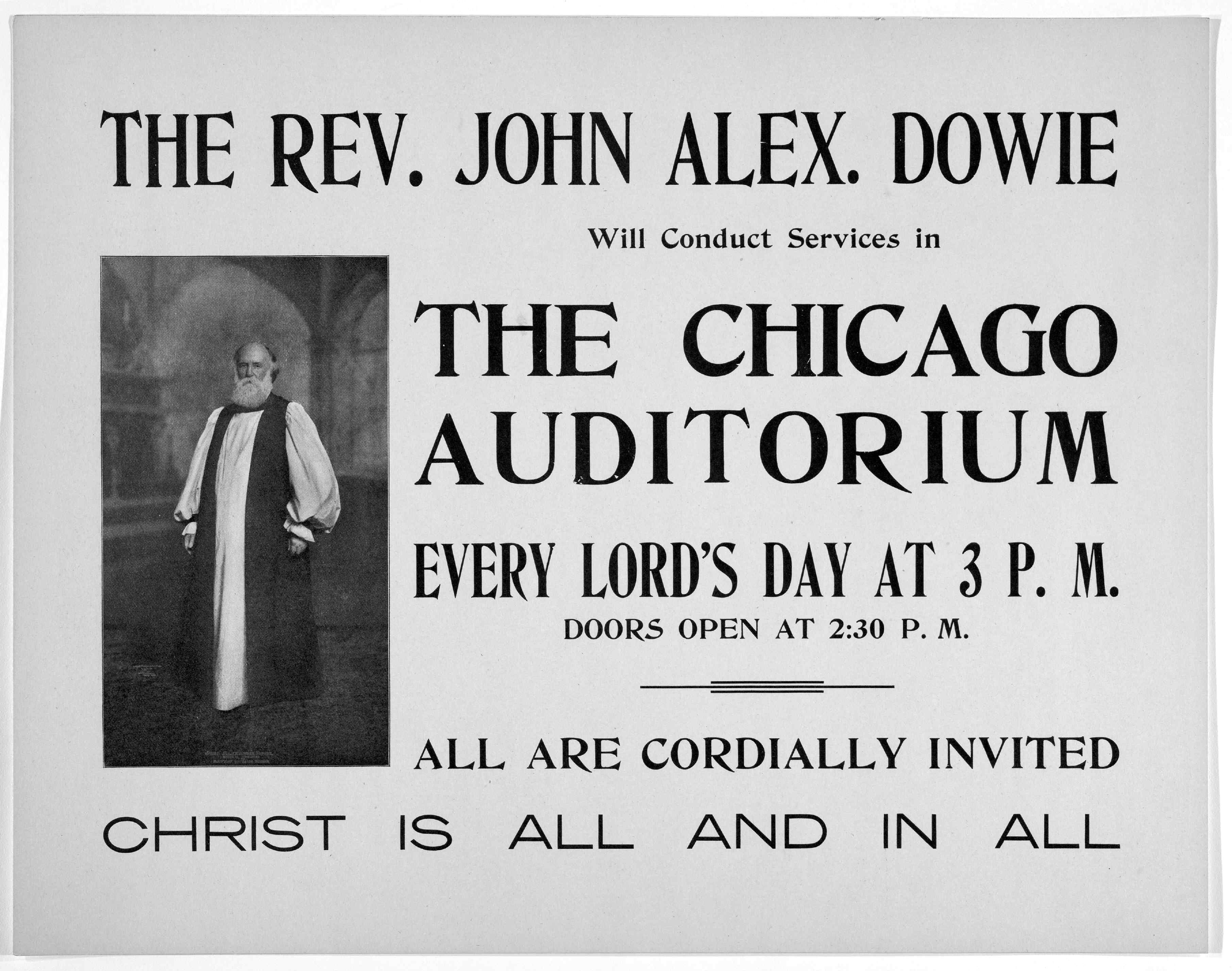

A year later he launched his healing ministry. After stints in Australia and California, Dowie moved to Chicago and opened a church near the site of the 1893 World’s Fair. Sadie Cody, who was in town to see her uncle Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show at the fair, went to see Dowie about a tumor in her back. After he laid his hands on her, Cody later said, she “felt a new life” inside her. The tumor vanished, and word of Dowie’s seemingly miraculous healing powers spread quickly.

In his lifetime, Dowie claimed to cure scores of serious afflictions, including smallpox, cancer, broken limbs, and blindness, as well as lesser ailments like asthma and arthritis. Medical doctors and mainline Protestant ministers, however, dismissed Dowie as a charlatan, noting that many of the illnesses he claimed to cure were psychosomatic, while the most dramatic healings were obviously staged.

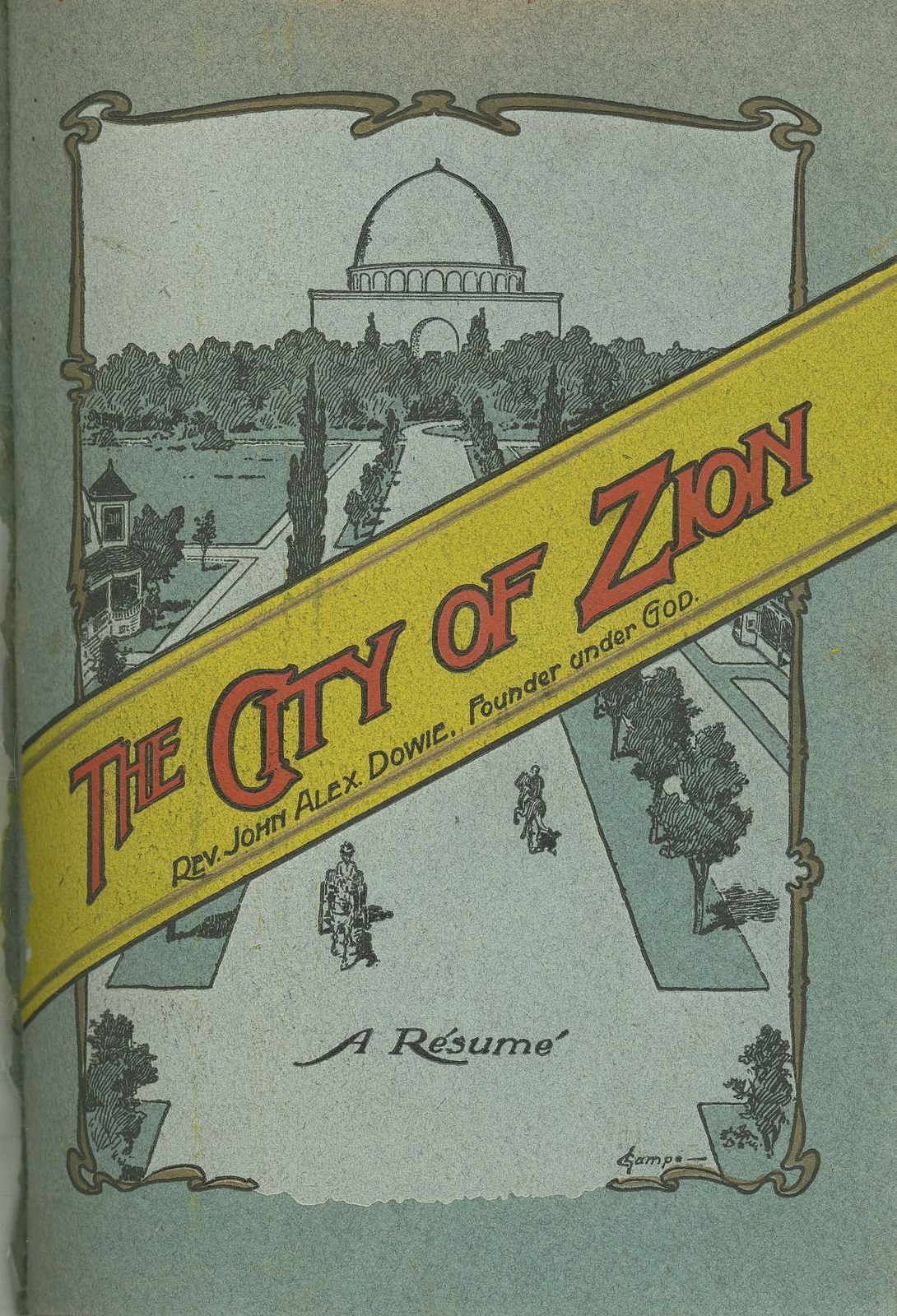

Nonetheless, Dowie’s flock multiplied rapidly, and by 1901 he had amassed enough followers to establish his own version of utopia, a biblical city built from scratch on 10 square miles of farmland 40 miles north of Chicago.

He named the city Zion and proclaimed it a theocracy governed by “the will of God.” Dowie was scornful of the U.S. Constitution, which, he noted, was “capable of amendment and improvement in a Theocratic direction.” Dowie owned everything in Zion: the lace factory, the general store, the bank—even the homes his followers lived in. It was the ecclesiastical equivalent of a company town.

Zion’s residents were required to comply with Dowie’s strict interpretation of the scriptures. “Billboards at the cross streets caution one that swearing or smoking or bad language of any sort are not allowed,” one visitor noted. Also banned: saloons, pork, medical practices, gambling halls, drug stores, and fraternal lodges. Zion’s residents were also required to tithe 10 percent of their income to Dowie.

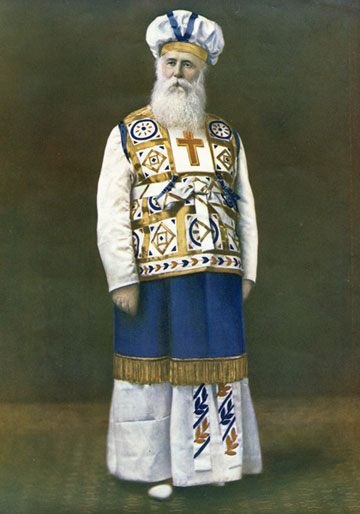

With his bald head and flowing white beard, Dowie certainly looked like a biblical prophet, and he played the part with aplomb. He appointed himself “General Overseer,” first over Zion, then over all Christendom. “The time has come,” he announced; “I tell the church universal everywhere, you have to do what I tell you … because I am the Messenger of God’s covenant.”

Dowie proclaimed himself Elijah the Restorer, sent by God to prepare the world for the second coming of Christ. Since his mandate was catholic—that is, universal—Dowie named his church the Christian Catholic Church. (The C.C.C. was in no way affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, which Dowie considered irredeemably apostate.)

By 1902 Zion’s population had swelled to 10,000, and Dowie claimed 150,000 followers worldwide. He had also amassed a fortune in excess of $10 million. His annual income from tithes alone was reported to be $250,000. One contemporary scholar has dubbed him a “religious robber baron.” Dowie was not ashamed of his wealth, and he lived in unabashed luxury. “Jesus came to make His people rich,” Dowie preached. Not in the “life to come,” but a “hundredfold now in this time.”

With Zion established, Dowie aimed for new worlds to conquer. He dispatched missionaries to Africa, and he set his sights on America’s undisputed capital of wickedness: New York City. In November 1902 he unveiled a plan to “restore New York” and to “sow New York knee-deep in Zion!” In autumn of the following year, he would bring his “full gospel message of salvation, healing, and holy living to the Gothamites.”

At the time, New York certainly could’ve used a little salvation. Manhattan was so mired in decadence that it was nicknamed the Island of Vice. As Richard Zacks explained in his book of that name, “New York reigned as the vice capital of the United States, dangling more opportunities for prostitution, gambling, and all-night drinking than any other city in the United States.” As a New York police commissioner, even Theodore Roosevelt had been powerless to tame the city. But John Alexander Dowie was determined to succeed where the hero of San Juan Hill had failed.

Three thousand Zionites eagerly volunteered for the crusade. All through the summer of 1903, they immersed themselves in planning. They pored over New York maps and travel guides. Some studied foreign languages so they could evangelize in immigrant neighborhoods. A guidebook published for the crusaders included helpful tips: “Do not make a confidant of a stranger, no matter how agreeable he or she may be. If in need of information on the street ask a police officer.”

On Saturday, October 17, 1903, eight trains carrying Dowie and his “Restoration Army” converged on New York City. While his followers traveled in coach, Dowie rode in a lavishly appointed private Pullman car.

Dowie’s evangelists were instantly recognizable by the black leather satchels they carried and the greeting they habitually uttered: “Peace to thee.” They canvassed tens of thousands of homes in the city, as well as countless saloons, gambling halls, and brothels. They preached on street corners, and handed out pamphlets promoting rallies and healing services at Madison Square Garden, which Dowie had rented for two weeks.

But dissolute New Yorkers were in no mood to be lectured by a horde of bible-thumping hicks from the Middle West. Almost everywhere they went, the Dowieites were greeted with jeers. The rallies at Madison Square Garden were a catastrophe. Dowie’s longwinded and incoherent sermons were frequently interrupted by catcalls and hisses. One especially unruly meeting was cut short by police who feared a riot would erupt. Amid cries of “Blasphemer!” and “Imposter!” Dowie was forced to flee the arena for his own safety.

The healing services were equally shambolic. All candidates were carefully screened before entering the “healing room.” Those granted an audience with Dowie were asked to surrender their wealth to the Christian Catholic Church if they were healed. Revolts ensued. “The indignation of the invalids was intense,” a reporter said of one botched healing service. “Many of them were on crutches, others were blind, while a few left the beds to test the treatment.”

“Those who go to Dowie for healing and are not healed,” another reporter noted, “are simply accused of being short on faith, and Dowie lets it go at that.”

The New York papers were scathing in their contempt for the crusade. The Examiner dismissed Dowie as “a coarse-grained, low-minded, shame-bereft, money-greedy adventurer.” His followers, the paper added, were “weak-framed, dull-witted creatures who crave a master as a dog does.”

The criticism infuriated Dowie, who was accustomed to nothing but fawning audiences. He did not take kindly to being called a fool, and he responded with vitriol. In his sermons at the Garden he denounced his critics in the press, in the mainstream ministry, and in the audience as “dogs,” “flies,” “rats,” “maggots,” “lice,” and “pigs.”

The New York crusade was an unmitigated disaster. The Christian Catholic Church gained just 125 new members. More ominously, the enterprise cost the church an estimated $300,000, pushing it to the edge of bankruptcy. Soon more financial problems arose. An investigation determined that Dowie had been using Zion’s bank “as his personal piggy bank.” There was discontent in the flock. Dowie suddenly appeared fallible in the eyes of his followers.

In 1905, one of his top lieutenants, Wilbur Voliva, orchestrated a coup, charging Dowie with “extravagance, hypocrisy, misrepresentations, exaggerations, misuse of investments, tyranny and injustice.” Voliva was installed as the new leader of the church, a position he would hold until his death in 1942. By then, Zion had become thoroughly secularized, just another sleepy suburb of Chicago. The old religious laws were either repealed or ignored. Utopia was dead.

After he was deposed, John Alexander Dowie went abroad to escape his creditors. He died in 1907, just two years after his fall from grace. He was 60.

Dowie’s enduring influence, however, is undeniable. Despite his unorthodoxy, he is still considered one of the founding fathers of modern American Pentecostalism, the branch of Christianity that emphasizes faith healing. His conspicuous consumption paved the way for modern televangelists like Creflo Dollar and Joel Osteen, who preach a so-called prosperity gospel. Dowie is also the spiritual antecedent of unsavory faith healers like Peter Popoff and Oral Roberts, “miracle workers” who have been exposed as frauds.

Dowie’s legacy also endures a long way from Zion, Illinois. One of the missionaries he dispatched to Africa, Daniel Bryant, was an especially efficient evangelist. In 1904 he converted a Zulu chief named Joseph Kumalo; thence Dowieism spread like a brushfire. Today, an estimated 15 million people in six nations in southern Africa belong to so-called Zionist Christian churches. These churches continue to adhere to many of Dowie’s teachings, particularly a belief in faith healing.

It’s likely that few members of these churches are even aware that the Zion in their denomination’s name refers not to the biblical Zion, but to an American hamlet on the windswept shores of Lake Michigan.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook