The Wild Ancient Greek Drinking Game That Required Throwing Wine

Strategic flicking was the name of this game, known as kottabos.

Spilling red wine may be the ultimate party foul, especially if it lands on the host’s couch or carpet. But for the ancient Greeks, a party wasn’t good unless the wine flowed freely. The Greeks didn’t just fling their glasses of wine about willy-nilly, though. This game of wine-slinging—known as kottabos—had a discernible target, and both pride and prizes were on the line.

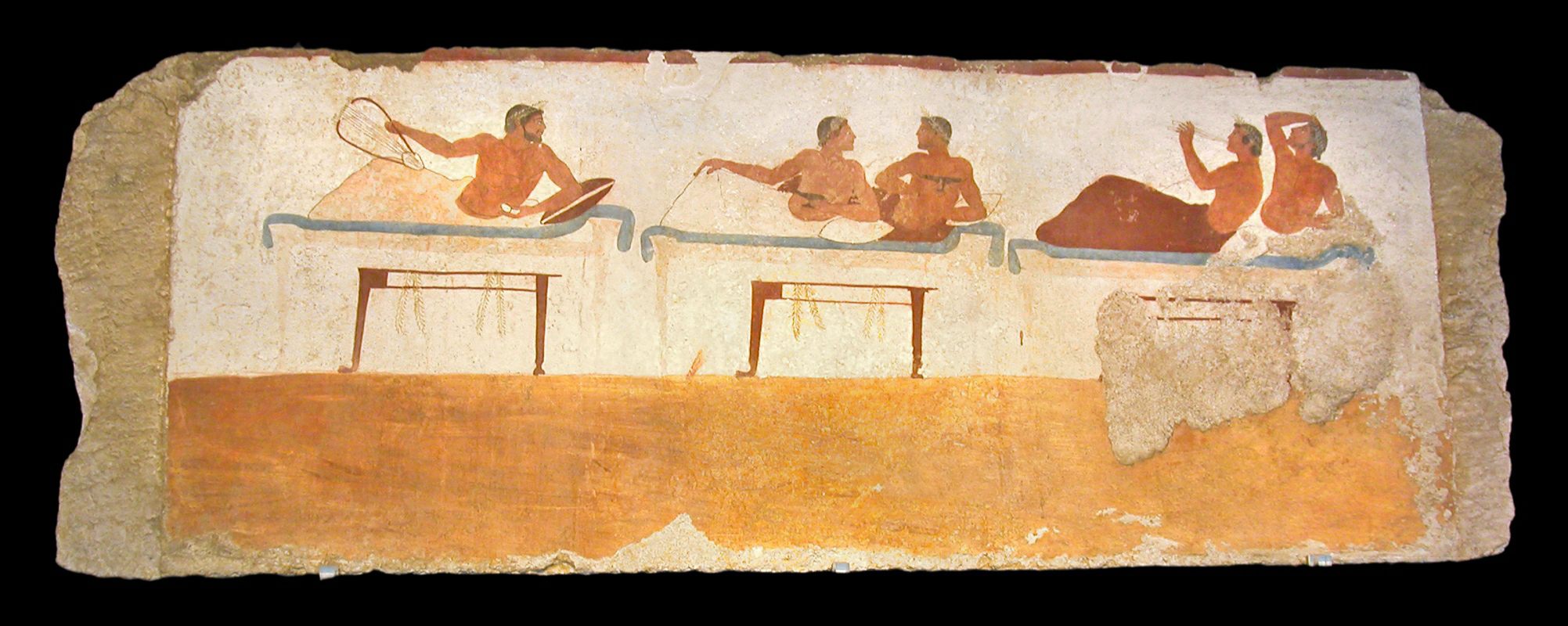

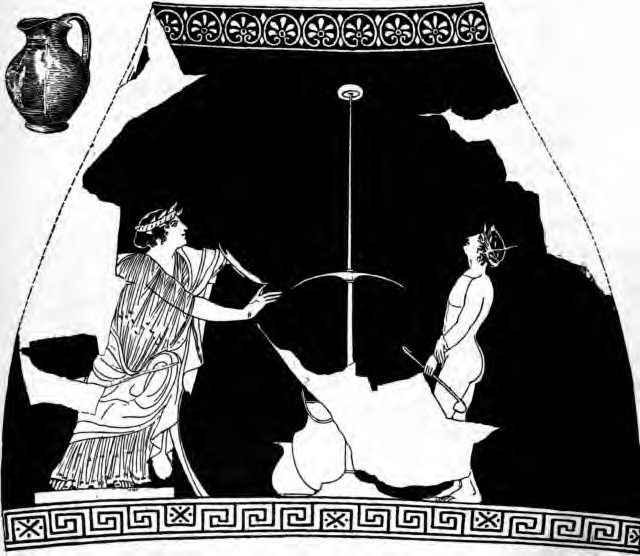

Kottabos had two iterations. The preferred way to play, which is the iteration often depicted in plays and especially on pieces of pottery, involved a pole. Players would balance a small bronze disk, called a plastinx, on top of it. The goal was to flick dregs of one’s wine at the plastinx so that it would fall, making a clattering crash as it hit the manes, a metal plate or domed pan that lay roughly two-thirds down the pole. The competitors reclined on their couches, arranged in a square or circle around the pole a couple of yards away. Each then took turns launching their wine from their kylix, a shallow, circular vessel with a looping handle on each side.

A less common version of the game featured players aiming at a number of small bowls, which floated in water within a larger basin. In this case, the object of the game was to sink as many of the small bowls as possible with the same arcing shots. Since it lacked the resounding clang of the plastinx striking the manes, this version of kottabos has been regarded as the quieter, more civilized way to play.

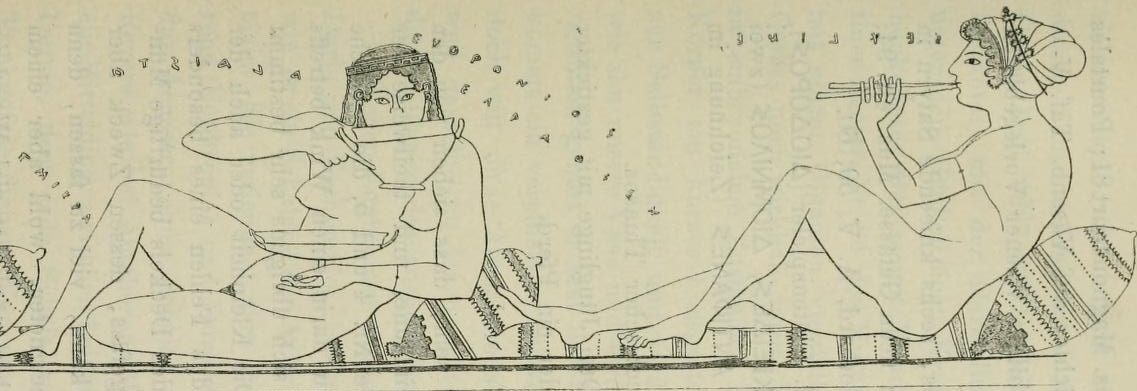

Technique was essential to maintain elegant form, accuracy, and to avoid spilling on oneself. The player, sprawling on a drinking couch and propped up on their left elbow, placed two fingers through the loop of one handle and cast the wine dregs in a high arc toward the target. The technique has been likened to the motion of throwing a javelin, due to the way the player threaded their fingers through the handle the same way one held the leather strap used to throw the spear.

Critias, the 5th century academic and writer, wrote about this “glorious invention” stemming from Sicily, “where we put up a target to shoot at with drops from our wine-cup whenever we drink it.” While a handful of modern academics question the game’s Sicilian origins, kottabos definitely spread throughout parts of Italy (as the Etruscans played it) and Greece, too. The kottabos craze even resulted in industrious people building special round rooms where it could be played, so all competitors could be equidistant from the target.

Naturally, kottabos made a frequent appearance at drinking parties known as symposia. But a few years ago, Dr. Heather Sharpe, the Associate Professor of Art History at West Chester University in Pennsylvania, brought the game into a sphere that’s perhaps more evocative of how we use the word “symposium” today: academia. Having seen the game portrayed in so many of the pots they were studying, she and her students decided to play a few rounds of kottabos using kylixes that a colleague, Andrew Snyder, made for them using a 3-D printer.

Since they were on campus, Dr. Sharpe and her students used diluted grape juice rather than wine. “Within about half an hour there was diluted grape juice everywhere, which made me realize it must have gotten pretty messy,” she says. “You’re aiming at the target, but the funny thing is these symposia were typically held in a more-or-less square room, and you had participants on 3 ½ sides. So if you missed the target it wouldn’t have been surprising if you hit someone across the room.”

The recreation also proved that the temptation to take a shot at a rival across the room must have been strong. In fact, in Aeschylus’s play Ostologoi (The Bone Collectors), Odysseus describes how during a game of kottabos, Eurymachus, one of Penelope’s suitors, repeatedly aimed his wine at Odysseus’s head, rather than at the plastinx, to humiliate him. And it seems that players took the game seriously, too, in spite of their casual reclining poses. “It’s funny because they did seem to be pretty competitive about this,” says Dr. Sharpe. “The Greeks, in a strange way, loved competing against each other, whether in the symposium or out in the gymnasium.”

Nonetheless, these were not high stakes contests. A winner might typically receive a sweet as a prize. Playing for kisses or other favors from attending courtesans (hetairai, as they were called) was also a possibility. Vases portraying kottabos reveal that women played the game as hetairai, too.

But eroticism didn’t just stop at prizes. It was customary to dedicate one’s throw to a lover, with the implication that success at kottabos augured success in one’s love life. Others didn’t mince words. In one poem, Cratinus recalls a hetaira dedicating her shot to the Corinthian male organ: “It would kill her to drink wine with water in it. Instead she drinks down two pitchers of strong stuff, mixed one-to-one, and she calls out his name and tosses her wine lees from her ankule [kylix] in honor of the Corinthian dick.”

It seems that kottabos’s free-wheeling nature and prizes weren’t enough to sustain it as a game, though. It eventually disappeared from artwork and plays, which suggests that it faded from popularity in the 4th century BC. The experiments of Dr. Sharpe and others aside, it seems unlikely to see a revival. Part of that might be due to how difficult it is to play, which doesn’t get any easier after players have had more than a few glasses of wine. The inevitable cleanup afterwards is a deterrent, too.

Just ask Hugh Johnson, the wine expert and author, who once tried his hand at the game. “I have had a kottabos stand made, and practiced assiduously,” Johnson recalls in The Story of Wine. “From personal experience I can say it is not all easy … and it makes a terrible mess on the floor.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook