The Neon Motel Signs of Las Vegas Aren’t Dead Yet

A photographer captured their flickers of life.

If you had driven from Los Angeles to Las Vegas in the middle of the 20th century, you would have spent several hours on some very dusty desert roads, past cacti and shaggy yucca trees, maybe a coyote howling beneath a sky pricked with stars.

Along that route, and inside the Vegas city limits, a motel sign had a tough job to do. It had to catch drivers’ eyes during the day, and be equally or even more inviting against an inky sky. In a flat, dry sea of boxy, nondescript buildings, signage was what differentiated one low-slung pitstop from another—and to make a sign pop, many mid-20th-century motels leaned on bright, buzzing neon. Those signs have since become as synonymous with the city as gambling, magic shows, and sin.

In addition to drawing attention, the signs ticked off the creature comforts that visitors should expect inside—from carpet to coffee, warm showers to color TV. They were often modeled on flora and fauna drivers might have streaked past in the desert, or the dueling mythologies of the developing desert town. Cowboys smiled down from some, while others—Jackpot, Bonanza, Roulette—nodded to games and good luck charms that came along with (or prevented) a good night’s sleep in Vegas. A few also celebrated the bets that the whole country was placing at the time, particularly on the space race, making rockets, stars, and moons common roadside sights.

Photographer Fred Sigman has been mesmerized by these neon signs since his first visit to Las Vegas as a teenager in the summer of 1968, when he and his father drove in from Hollywood, crossing the Mojave Desert in a Ford Falcon. On that trip, a young Sigman captured beguiling casino facades and glittering signs with his Polaroid Swinger. By the mid-1990s, he had become a professional artist, and accepted a commission from dealer and gallerist Ivan Karp to go out and focus on the city’s motel signs.

By then, the motel heyday was already over. “In the ’90s, [Vegas was] already shifting to mega-resorts on the strip,” Sigman recalls. In contrast to that glitziness, motels were considered “low-life, crappy little places.” Many of them had shuttered and falling into disrepair. Others were gone, bulldozed into oblivion. Sigman’s photos, shot with a large-format film camera, froze the signs within a landscape that was changing, complete with busted bricks and sidewalks, brown-tipped plants, and concrete pools filled with nothing but shadows. Now, more than 20 years later, Sigman has compiled his trove of photos into a book, Motel Vegas.

Sigman, who now lives mostly in Siem Reap, Cambodia, says he doesn’t pine for the “good old days” of Vegas. While the photos are saturated, bright, and graceful, he says they’re stripped of nostalgia. Traffic or trash appears at the edges of the frames, and “There’s nothing romantic about the lighting,” he says. “It’s not like a Turner painting or anything.” Sigman photographed some motels in harsh afternoon light, and others beneath skies smudged with pinks and blues, but not for the scenic qualities. He says he was just seizing opportunities to highlight the specific qualities of a certain sign. “I wasn’t there because, ‘Wow, sunset,’” he says.

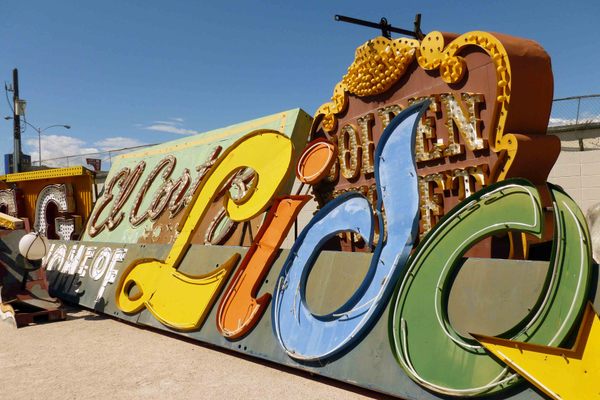

Many of the signs blinked out or disappeared since Sigman photographed them, but not all have been lost forever. Some were salvaged, shined up, and installed in areas such as East Fremont, a district once awash with motels and currently undergoing a revitalization project, the Las Vegas Review-Journal reported in 2018. There, a few old signs found new life as artworks. “You can see them from your car, the way it used to be,” Sigman says. More are on display at the Neon Museum, where several have been fully restored and relit, with many more heaped outside, in the Neon Boneyard, where visitors are free to wander among the pretty scraps of Vegas’s past.

Meanwhile, the city’s Historic Preservation Commission is taking an inventory of motels past and present—reaching out to owners and sifting through archives of old advertising matchbooks and postcards—that once lined Fremont Street and Las Vegas Boulevard. They’re also trying to drum up enthusiasm for adaptive reuse projects that would freshen up some old motels to appeal to a new wave of travelers. “There’s a whole world of cultural tourists out there who go to museums and stay in boutique motels and they’re not into luxury, resort-style traveling,” says Jack LeVine, a local real estate agent and a member of the commission. There’s a hope that renovated places, like the 53-room Sterling Gardens, will charm the tourists looking for a cool, kitschy place to crash.

A few motels are still open for business, promising the same unfussy accommodations they’ve been offering for decades. And while Sigman, who rides a motorcycle and says he “spends more time in airports than anywhere else,” has an unvarnished view of these sometimes-seedy spots, he appreciates an invitation to stop and rest his bones for a few hours before moving on. When you’re tired enough, it doesn’t take a lot to make a roadside stop feel like home, if only for a night or two.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook