The Mansion of America’s First Black Female Self-Made Millionaire Gets a New Life

As a think tank for female entrepreneurs of color.

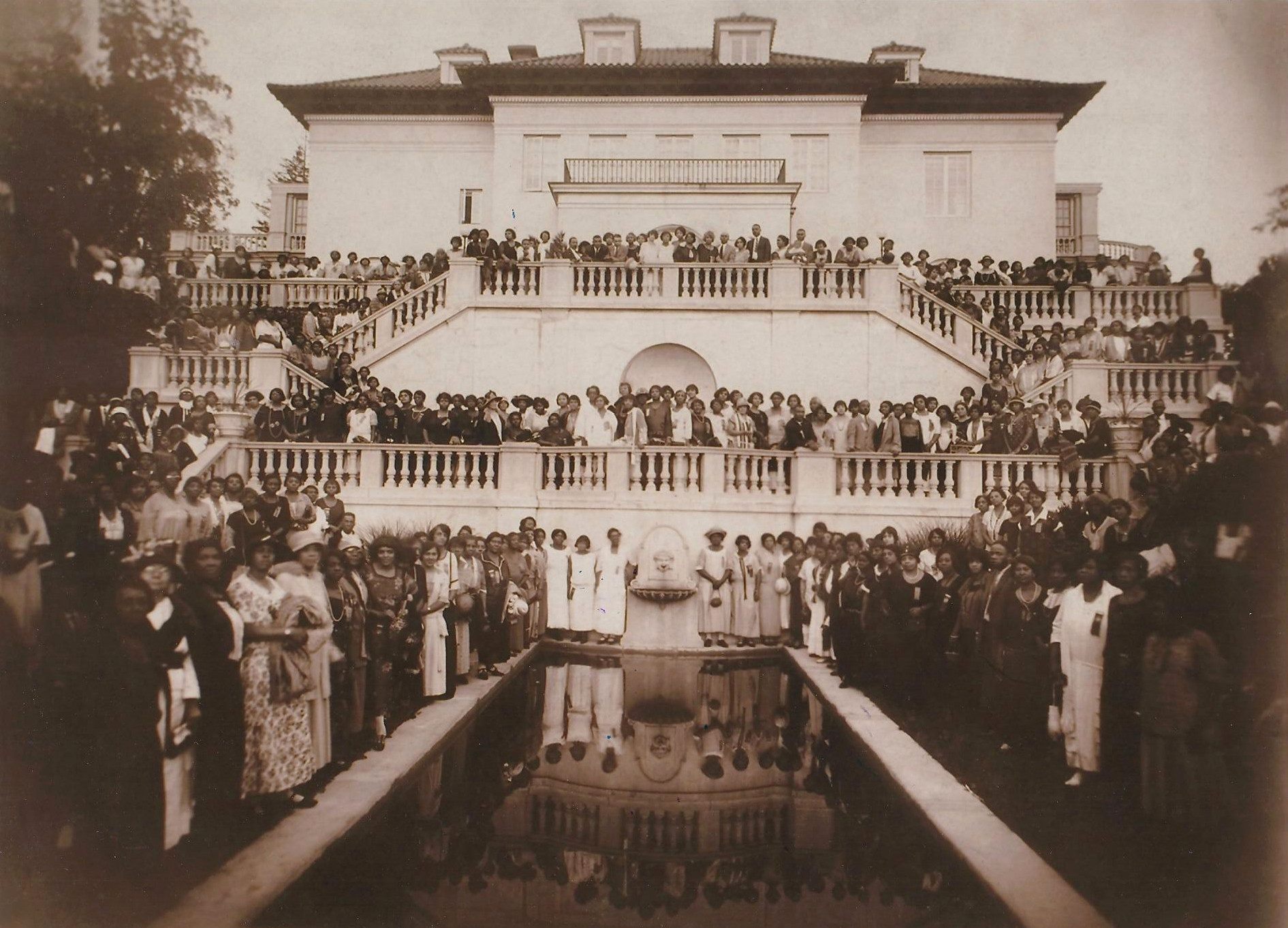

In 1916, America’s first black female self-made millionaire, Madam C.J. Walker, had a house built. And by house we mean mansion, one befitting her fortune and status, cleverly named Villa Lewaro—an amalgamation of her daughter’s first, middle, and last names (A’Lelia Walker Robinson). Walker was a trailblazing entrepreneur, and her beauty product company was at one time the largest black-owned business in the United States. Her Italianate villa in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, is now in its hundredth year, and is being reimagined as a learning and leadership institute for female entrepreneurs of color.

The 28,000-square-foot estate, designed by Vertner Woodson Tandy (the first licensed black architect in New York State), was recently purchased by the New Voices Foundation for an undisclosed amount. The foundation is the nonprofit branch of the New Voices Fund, a $100 million investment fund dedicated to entrepreneurs following in Walker’s footsteps. Both the fund and the foundation were created by Richelieu Dennis, a Liberian entrepreneur and investor, who will help oversee the transition of Villa Lewaro from a riverfront estate to a creative think tank. It’s notable that Dennis’s family founded Shea Moisture hair products, a business, like Walker’s, that was built on a family recipe for African-American beauty needs.

Though Walker only lived at Villa Lewaro for one year (from May 1918 until her death in May 1919), over time the home served as a cultural and intellectual meeting place for leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Zora Neale Hurston and W.E.B. DuBois. Ultimately, the mansion “represents the fulfillment of Madam Walker’s goal to inspire future generations of African Americans and women,” says A’Lelia Bundles, great-great granddaughter of Walker.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Walker was the first person of color to own property in tony Irvington. Villa Lewaro was situated along the aptly named “Millionaire’s Row,” so the beauty pioneer counted the Rockefellers and Astors as neighbors. A November 4, 1917, New York Times Magazine article reports that Walker’s move into the neighborhood was met with total disbelief. The article details the inside of Villa Lewaro, too. “It is 113 feet long, 60 wide, and stands in the centre of a four-and-a-quarter-acre plot. It is fireproof, of a structural tile with an outer covering of cream-colored stucco, and has thirty-four rooms. In the basement are a gymnasium, baths and showers, kitchen and pantry, servants’ dining room, power room for an organ, and storage vaults for valuables.”

All this belonged to a self-taught woman from the sharecropping South, who founded a company with a 3,000-person salesforce and up to $250,000 in annual sales (several million in today’s dollars). Walker also had a reputation for being an activist and major philanthropist for the black community. Throughout her life, she bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, schools, and other cultural institutions. In 1919, just before her death, she gifted the equivalent of $65,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund—their largest gift ever at the time.

Villa Lewaro was named a National Historical Landmark in 1976. In 2014, it was named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The New Voices Foundation is working with preservationists to ensure that the mansion is structurally sound, and with historians to give context to the time and place in which Villa Lewaro was built and furnished.

Bundles, a biographer and brand historian beyond being Walker’s descendant, looks forward to meeting the first cohort of entrepreneurs to use the space. “I hope their visit will inspire even more success [and] I hope they’ll incorporate Madam Walker’s practice of being a patron of the arts and a philanthropist who supported political, civic, and social justice causes,” she says. No centennial events have been announced for Villa Lewaro just yet, but the Madam Walker Legacy Center, an arts and culture space in Indianapolis (which hosted her company’s headquarters), will reopen this year after a renovation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook