The Priest Who Resurrected an Island’s Cider Tradition

Father Rui Sousa saw opportunity in the parish orchards.

What first struck Father Rui Sousa was the abundance of fruits in the church’s countryside orchards: different varieties of pears, passion fruit, raspberries, and apples, often abandoned and left to rot. It was the late 1990s, and as the new head of the parish of Prazeres, in the middle west region of Madeira, the famous subtropical Island of Portugal, he decided that the farm could do better.

Father Rui (as locals know him) wanted Quinta dos Prazeres to become a community project, fostering appreciation of the rural environment while being profitable for the Catholic Church, whose parishes have a long history of supporting themselves and local charity through small businesses, especially food and drink. He also wanted to preserve local plants, especially pome fruits, that he, a Madeira native, had only seen on the island.

Focusing on the piles of rotting apples, Father Rui secured permission to build a warehouse and make cider. When accompanying workers into the fields, the priest picked every kind of apple, doing the same in neighbors’ fields, and tested their potential for cider. He didn’t know it yet, but his experiments would transform a languishing, 600-year-old tradition of making Madeira cider.

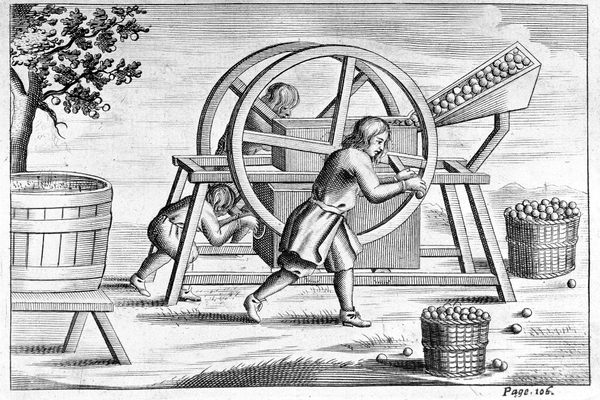

One of Father Rui’s favorite childhood memories is his father making cider in their garage. When he came across the apples in the Prazeres orchards, he recalled his father, like many of their neighbors, squeezing apples in his hand press made of wooden boards.

But rather than just replicating his father’s artisanal methods, Sousa wanted to focus on quality. He requested the help of the Madeira government’s Regional Directorate of Agriculture, and agronomist Regina Pereira, who had just left a position at a local wine cellar, started working closely with the priest.

“When I arrived, the cider produced in Prazeres was very inconsistent and acidified very quickly,” she says. “I talked to the priest, and we identified the main flaws and changes we should make right from the start.”

In 2007, they released their first cider, made with different native varieties from the island. The pale-yellow cider was dry, with balanced, fruity acidity, without the strong bitterness that defined Madeira’s artisanal ciders. Thanks to the controlled production methods introduced by Pereira, they soon obtained local licenses to commercialize the cider, opening a new chapter in the Madeira market, where cider was, like moonshine, typically made at home and neither bottled nor labeled.

“The cider started to gain a reputation as more people tasted it. Some loved it, and others hated it,” Pereira says. For many, it had an unfamiliar profile: less acidity, without the characteristic cloudiness. Father Rui’s father, he says, told him, “Oh boy, I have always educated you not to change any product or deceive people. You’re putting water in this cider.” The clearer color and lighter aroma was very different than the cider they’d made in his garage.

Like England, France, and Spain, Portugal has had a relationship with cider since the Romans spread the Celtic beverage, with the Moors’ agricultural prowess shaping the apple scene on the Iberian Peninsula. Over the years, however, cider production dwindled as people moved from the countryside to the cities. In Madeira, local wine became one of the most valued vintages in the world, butting out cider production.

But it was never fully abandoned in Madeira’s mountainous regions. “Where I grew up, called Santo da Serra, people called cider ‘wine of the land,’ because there was no chance of growing grapes at that altitude,” says Sousa. In those areas, residents produced and drank cider at home, at parties, and at family gatherings, or in a few taverns and bars that insisted on serving them.

What makes Madeira cider special is the island’s unique geography, or terroirs, which are home to a great diversity of apples, many of them native or traditional to the island. About 70 years ago, more than 100 varieties of pome fruits grew throughout the archipelago. Today, only around 30 of them remain, such as Cara de Dama and Barral varieties.

Such a wide array of fruits produce different beverage profiles: from light in color to almost coppery, honey and caramel in flavor and aroma to red fruits and flowers. “In this diversity, there is also an endless wealth of aromatic profiles, depending on the altitude, the incidence of sun, and other natural characteristics,” says Pereira. The proximity of the sea gives a salinity to the fruits and a more acidic pH to the soil.

The success of Prazeres’ first cider led other producers to request technical assistance from the government. Pereira expanded her trainings, and the government supported the building of new cider mills. Today, producers leave from the island’s three mills each season carrying their neatly labeled bottles, which are ready for shop shelves or restaurant fridges. Around 30 local producers, many of them small farmers, also created a Madeira cider association and jointly applied for PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) status, which was approved by Portugal and is under consideration by the European Union.

Thanks to these efforts, local cider gained greater awareness among Madeirenses and started popping up more in bars and restaurants. Last May, the government, in partnership with the association, promoted the first official tasting of Madeira ciders. “I was very impressed with the quality of the ciders, although I was initially skeptical,” says sommelier Bruno Antunes. “The different sensory profiles displayed definitely blew my mind.”

To identify the pomme fruits that can generate the best sensory (or organoleptic, in professional jargon) profiles in the glass, Father Rui has spearheaded a new project at the cider mill he built right by Quinta dos Prazeres. His focus, which is increasingly popular, is choosing specific apples for their cider-friendly flavors—rather than blending all kinds of apples or using the most common variety. He’s found that the familiar Golden Delicious apple gives more structure to the ciders and the tiny, rounded, reddish Ponta do Pargo, a native of Madeira, generates a more aromatic, fruity cider.

“At first, I just wanted to recover some apple trees at the church’s farm and prevent some native species from being lost,” says Father Rui, who is no longer in charge of the parish, although he continues to produce ciders. “I had no idea I was actually leading a revolution around here.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook