To Make Fracture-Resistant Concrete, Let a Sea Urchin Be Your Guide

Strong and flexible building materials, inspired by ocean life.

Sea urchins are covered by a thicket of spines. In the vernacular of Middle English, urchun meant “hedgehog,” but the echinoderms’ sharp, sometimes venomous protrusions are anything but cute. But some researchers propose taking another perspective on them by looking closely at their internal structure. It could, if you squint a little, offer a blueprint for more resilient building materials.

In a paper recently published in Science Advances, researchers from Germany’s University of Konstanz and University of Stuttgart propose that the sea urchin spine is a pretty good model for improving concrete. Since it was introduced by the ancient Romans, who molded it for the Pantheon’s dome, the material, which is often made by combining coarse crushed rocks or gravel with finer grains of sand, plus cement and water, has been poured in veritable oceans. The United States produced more than 83 million tons of concrete in 2016 alone.

Because concrete isn’t very elastic and is prone to cracking, it’s often reinforced by steel rebar or other supports. Sea urchin spines could be brittle, too, because they’re made from fragile calcite, but they manage to be pretty durable, the researchers write, because they’re stacked like bricks, layered with softer calcium carbonate that prevents them from splintering.

“Our goal is to learn from nature,” said Helmut Cölfen, one of the researchers, in a statement. Plenty of engineers are putting stock in biomimesis, or looking to nature to resolve vexing design questions. A lab at the University of Cambridge, for instance, is imagining buildings inspired by the properties of bones or eggshells. In this case, researchers thought that the layering of soft and hard materials seemed promising. But it is a hard idea to bring to concrete, since all its ingredients are swirled into a homogenous slurry.

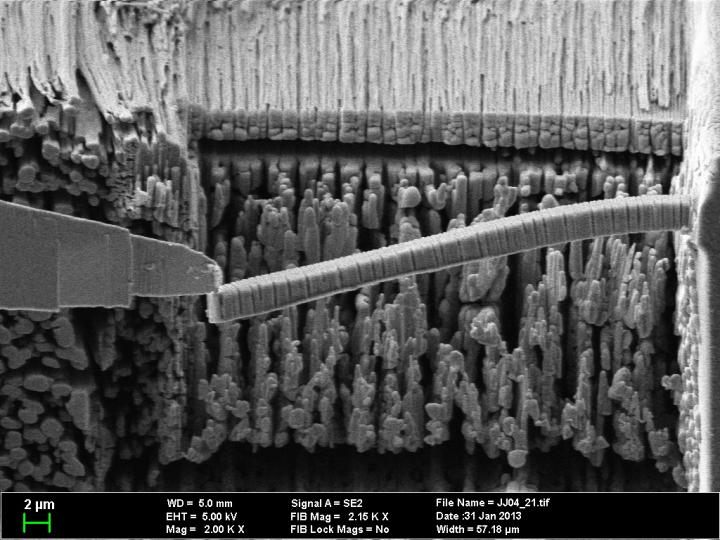

With the sea urchin’s resilient design in mind, the team zoomed way, way, in to nanoscale level. There, they were able to synthesize a material that bound itself only to the cement, and not other materials in the mixture. That made it possible to achieve the stacking of strength and flexibility that they observed in the spines. “If we succeed in designing the structures of materials and reproduce nature’s blueprints, we will also be able to produce much more fracture-resistant materials,” Cölfen said. The researchers suggest that the technique yields a substance between 40 and 100 times more fracture-proof than standard concrete.

Skyscrapers are getting bigger and bigger, so architects and engineers are going to have to get creative in their materials. Turns out the ocean floor might be a good place to look for inspiration.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook