This Artist Sculpts Animals and Flowers From Grains of Rice

Guorui Chen brought a hometown tradition back from extinction.

No one is pickier about rice than Guorui Chen. The 33 year old only accepts rice grains longer than 7 millimeters (1/4 inch), and they have to be white, clear, straight, and undamaged. Every day, he separates intact grains from broken ones with a winnowing basket and then spends hours examining their transparency under a light.

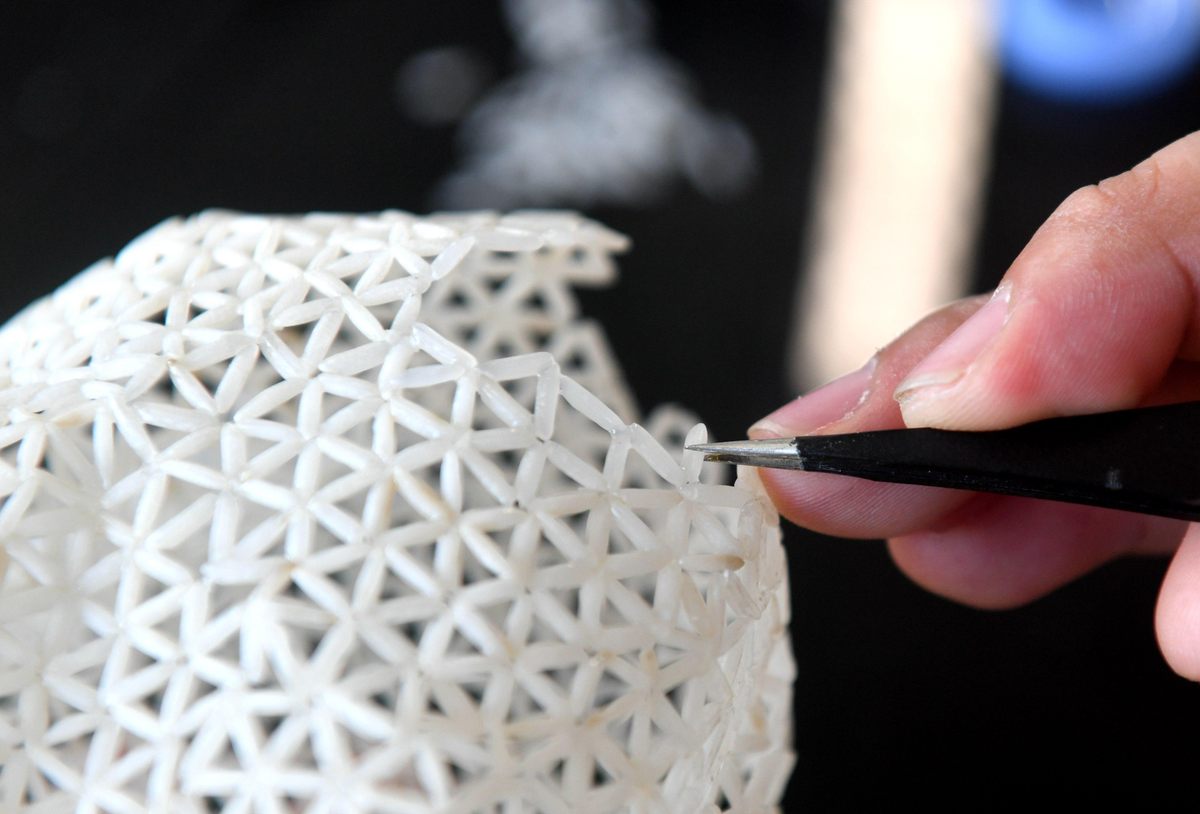

But Chen won’t cook this rice. Instead, he turns it into art. He picks out three grains, glues them end to end into a triangle, and connects hundreds of these basic units to form shapes: a horse, a lotus flower, a temple. In his hands, rice turns into aesthetic hollow sculptures. They appear so delicate that every joint looks liable to break, but in fact, they are sturdy enough to be lifted up and moved.

In a country with over a billion people who eat rice almost every day, Guorui Chen is the only one using rice to make Gaolou Rice Strings, a traditional art that had been lost for decades. “Nowhere else in the world can you find it,” says Chen.

Chen was born in Gaolou, a small village on the southeast coast of China where this art originated 150 years ago. However, when an octogenarian who migrated to Singapore decades ago came back to the village in late 2015, no one made these sculptures anymore. Chatting with his townspeople, he reminisced about this traditional art and how every household would participate in an annual contest of building the most sophisticated rice strings.

“I was driven by curiosity at first,” says Chen, who visited the octogenarian for more information. With years of artistic training and an undergraduate degree in industrial design, he also felt that he was probably best equipped to revive the lost art. “I have the responsibility to carry forward this fantastic cultural tradition,” he says.

Chen learned that the practice peaked in the early 1900s but went extinct during the ‘60s and ‘70s, when the Cultural Revolution forced people to give up their traditional roots. The only written archive he could find was from an old genealogy book of the Chen clan, taken abroad by the emigrated members. And Chen never found an image of the art itself.

He used his imagination to turn the textual descriptions into his first attempt in February 2016: a two-dimensional lotus flower glued to a plate. In the meantime, Chen found a few seniors in the village who had seen the rice strings when they were children. He took his first creation to these seniors for feedback: the type of rice was wrong, the structure could be more complex, he had made other mistakes.

So Chen took their advice, revised his work, and took it to the seniors again. In mid-2016, he was able to recreate the art to their satisfaction. By now, he has finished more than a dozen Gaolou Rice Strings sculptures, ranging from a simple teacup that takes half a day of labor to a life-size rooster that requires almost a month.

The rooster is by far his proudest work. “I’m like a human 3D printer, envisioning the shapes in my head and then trying to put the pieces together,” Chen says. “Sometimes, the muscles in the leg were too big or too small, so I had to destroy the part I was not satisfied with and remake it.”

Chen knows that, even though he has done his best to reimagine the art, it won’t be exactly the same. He learned that the best rice material used by his ancestors was a kind of wild rice found on the tidal flats miles away from his village. The grains of this type of rice could grow as long as 0.7 inch, ideal for the construction. But decades later, what used to be uninhabited flats have been turned into urban areas. And the wild rice species has vanished from this part of the country.

Unable to use the traditional material, Chen went to the market and bought all kinds of rice to test. Surprisingly, the best substitute is not from China but Thai Jasmine rice, known for its long grains and fragrance. “Transportation and communication weren’t so developed in the past, so [the ancestors] had to work with what was there around them,” says Chen. “Now we can use rice from anywhere in the world.”

With new technology, he made other changes too. In the past, the art piece was only supposed to last a winter. But now, with help from a local university’s biology lab, Chen is able to preserve his work permanently in epoxy resin.

With no other person in the world making Gaolou Rice Strings, Chen is now working full-time in developing and teaching the art. He is discussing with local schools how they can teach it to all levels of students, from kindergarten to college. The future of Gaolou Rice Strings may depend on one of those kids clumsily gluing rice onto a plate.

It’s also about more than preserving the art. “What we are really handing down is the craftsmanship,” Chen says. “In this fast-paced society where many of us are losing our patience, what we are getting from [Gaolou Rice Strings] is more the experience, of seeing a world in a grain of rice.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook