The Savvy Marketing That Put Marshmallows on Your Sweet Potato Casserole

“I’ll have it with my Roast … and again for dessert.”

In mid-19th-century France, a single marshmallow was a confectionary miracle to be savored. Made from the sap of the mallow plant, whipped egg whites, water, and sugar syrup, each one was individually formed—only high-end confectioners need apply. This sticky and time-consuming task was near-impossible to reproduce at home. So marshmallows were correspondingly expensive, dainty treats. But in 1895, Joseph Demerath of Rochester, New York, managed to disrupt the time-consuming tradition and bring marshmallows to the masses. Within 30 years, Americans would be turning them into mayonnaise (!), salads, and the famous sweet potato casserole.

Instead of costly mallow gum, Demerath used gelatin. With this recipe and the recently invented whirling steam marshmallow machine, he could make mass quantities of white fluff quickly and easily. The Rochester Marshmallow Works inspired fleets of copycats and, by 1900, the confections were everywhere. At first, they were cast into domed squares. By 1911, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, you could buy them in the shape of cones, pears, bananas, rolls, blocks, fish, slabs, and (troublingly) babies. America had gone marshmallow-mad, and the mold was their oyster. (You could get them in the shape of clams, too.)

Marshmallows first made their way onto Thanksgiving tables as delicacies in their own right. In 1901, the New York Times described “marshmallow baskets,” which put the treats at center stage, as a popular Thanksgiving dessert. But people were beginning to think of marshmallows not just as standalone sweets but as ingredients—and advertisers took note.

In December 1915, an advertising and sales trade journal used Bunte Brothers’ marshmallows as a case study for “Advertising New Uses for an Old Product.” Until April 1914, they wrote, “marshmallows had been advertised as a confection, only.” But through clever marketing, “the marshmallow was no longer a mere confection, but a food, a table luxury, an essential ingredient of forty or more different kinds of delicious desserts.” (If only it stopped at desserts.) This campaign was what today might be called multiplatform—a free recipe book, direct-to-consumer marketing, streetcar posters, displays in store windows, and ads in newspapers and on billboards. “The appeal was to the palate, and also to the housewife’s interest in her table and problem in introducing greater variety into menus.”

That Bunte Brothers cookbook appears to have been lost, but the appeal was so effective that a number of other companies followed suit. In 1917, the Angelus company put out a booklet of recipes for marshmallow-based snacks, dishes, and meals, many of which were likely copied or cribbed from the Buntes’. The booklet contains the first known recipe for sweet potato casserole, and, citing this origin, Saveur writes the dish off as a monstrosity of effective marketing.

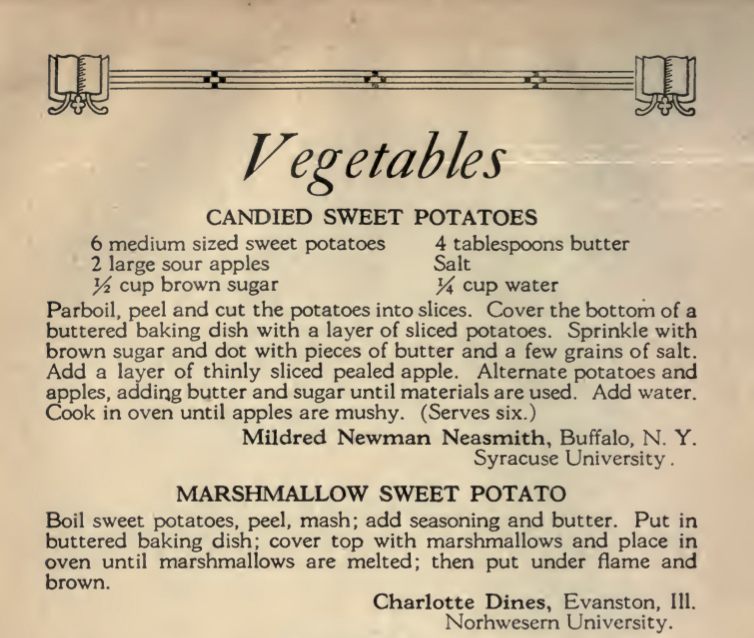

But there’s evidence to suggest that similar sweetened sweet potato dishes already existed, and that the marshmallow was just a shortcut to the same end. Candied sweet potatoes were an established part of American cuisine by the time Texas Farm and Ranch published Sweet Potato Culture for Profit: A Full Account of the Origin, History and Botanical Characteristics of the Sweet Potato in 1896, which includes a recipe for glazed sweet potatoes. Later, they would variously be said to be from Boston, the Old South, or the international Jewish culinary tradition. A cousin to these was “potato pudding,” the earliest known American recipe for which dates to the 1790s. This take combined mashed sweet potatoes with milk, nutmeg, and egg whites. Marshmallows, when they came, combined egg whites with sugar—a speedy workaround.

By 1918, just one year after the Angelus booklet, there was a variety of available recipes for the dish. These can be found everywhere from the trade publication Sweet Potatoes and Yams to the Women’s Patriotic League Cookbook, which charmingly and bafflingly called for “five cents worth of marshmallow.” By 1923, the dish was sufficiently entrenched to make its way into the college and grad school student–sourced The College Woman’s Cookbook. And in 1935, mixed with pineapple, it was touted as a tradition in the Southern Cookbook of Fine Old Recipes, with the subtitle, “(I’ll have it with my Roast … and again for dessert.)”

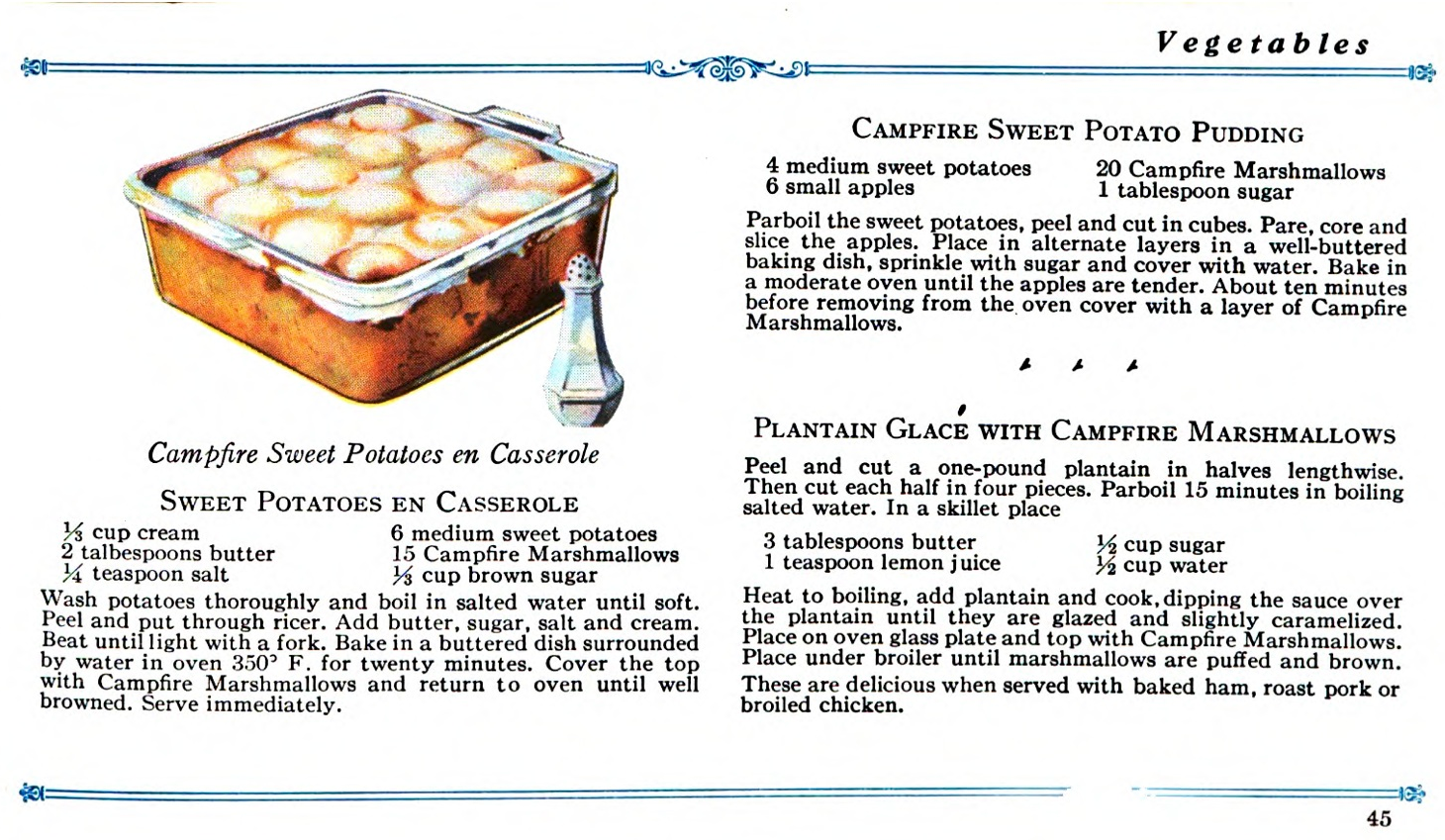

It’s no surprise that the recipe stuck—people simply love marshmallows. A 1918 edition of American Cooking gushes, of “The Magic of the Marshmallow”: “An indefinable flavor that bewitches the person who partakes! Many a common dish is enhanced by the addition of a few marshmallows or a marshmallow sauce.” But not all of these recipes became American classics. The Campfire company marshmallow recipe pamphlet, which came out shortly after Angelus’, promised: “There are also dozens of quite new and very interesting recipes—so attractive, indeed, that you will be anxious to try them at once.” Among them is “Campfire Unique Salad,” with 30 marshmallows, a can of sliced pineapple, a small cabbage, lettuce, ½ cup pineapple juice, and 12 maraschino cherries. It—like “Chicken Salad Supreme,” which swapped mayo for marshmallows and cream—is not exactly a beloved holiday staple.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook