Found: A Landlocked Message in a Bottle in a Detroit Train Station

More than a century ago, a couple of guys had some beer and an idea.

Many bottled messages start and end their lives on boats or shores—someone releases the stoppered dispatch into the water, and it drifts until it breaks or sinks or a lucky someone scoops it up. That’s how a sealed invitation to participate in a decades-old citizen science project swam around the Gulf of Mexico before washing up on Texas’s South Padre Island, and an amiable note sailed all the way from Bonn, Germany, to Auckland, New Zealand, after around seven years in transit. But in Detroit, one bottled message apparently never left land: Construction crews recently recovered it from a wall of Michigan Central Station.

When the Beaux Arts building opened in 1913, it was dazzling, with ornate columns and cornices. The grounds were somewhat elaborate, too, with grass and promenades flanked by rows of trees, Kelli B. Kavanaugh points out in a book about the building’s construction and decay.

The last train departed in 1988, and over the subsequent decades, the building slumped into disrepair. Ford Motor Company purchased the disheveled structure in 2018, and is currently restoring and renovating it to be a mixed-use space housing a mix of publicly accessible shops and restaurants and places for the auto company to design and test products.

The revamped building is slated to open in the next few years, but there’s a lot of work to tackle in the meantime. Lukas Nielsen and Leo Kimble, who work for a plaster restoration company, were on a scissor lift in May 2021 when Nielsen spied the bottle nestled amid some old crown molding. It was a strange place for a message in a bottle, nearly a mile from the Detroit River, which separates the city from Windsor, Ontario.

The glass was seafoam green, and though it had gone slightly milky with age, it was easy to see that a rolled-up note was stuffed inside. The bottle’s tattered label revealed that it once held beer brewed by Stroh’s, which set up shop in the city in the mid-19th century.

The bottle is marked with the year 1913, the year that the station opened. According to a Ford press release, the bottle has now made its way to the company’s archives in Dearborn, where it will join roughly 200 other artifacts salvaged from the building during the renovation, from buttons and shoes to elevator call buttons and train tickets. Eventually, some of those objects may return to the station, to be exhibited in the place where they were installed, shed, or stowed.

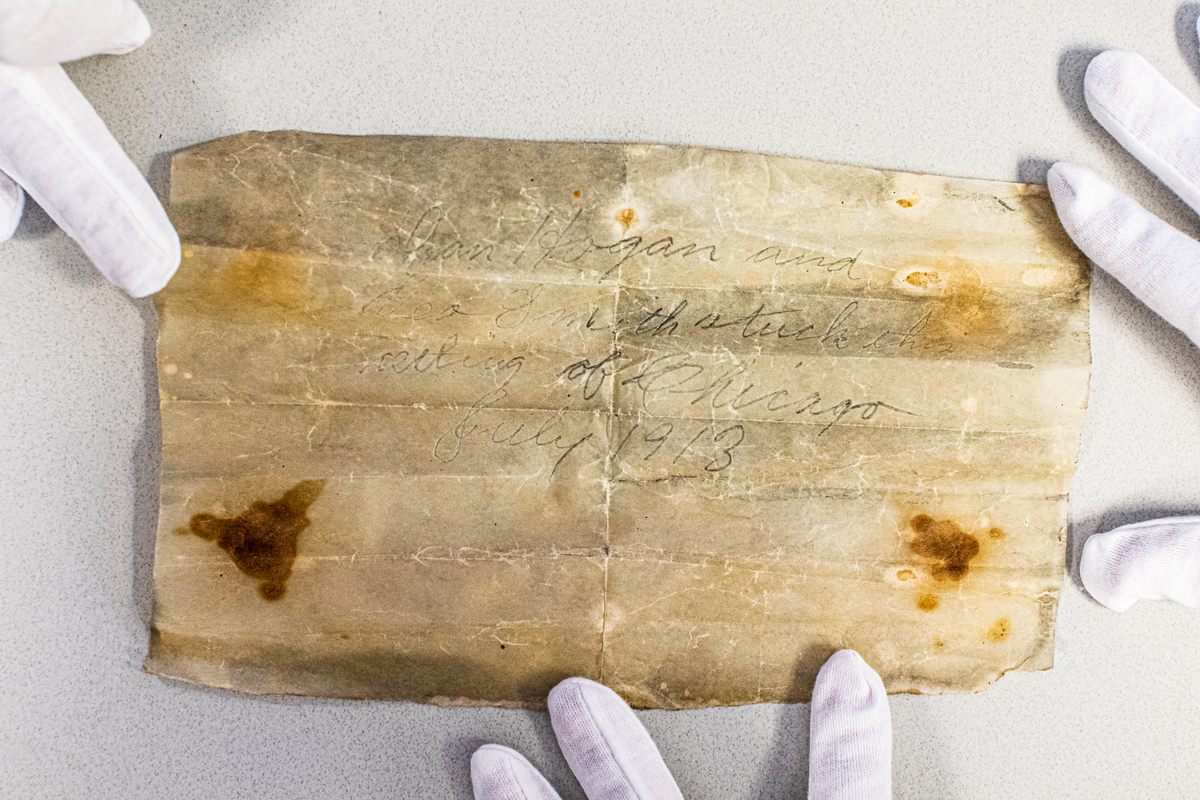

Wearing cotton gloves, the archivists used reverse tweezers to remove the letter, and carefully unrolled the note. It was jotted on waxy paper, “the kind you might wrap a sandwich in,” writes Leslie Armbruster, a Ford archivist, in an email. It’s fairly brittle, Armbruster says, but has held up pretty well.

Unfortunately for 21st-century snoops, there isn’t a whole lot to decode. The message, jotted in pencil, is short and only partly legible. It seems to read, “Dan Hogan and Geo [George] Smith stuck this. [indecipherable word] of Chicago 1913,” the Detroit Free Press reported.

Humdrum as that may be, the archivists figured the note would probably be blank, “So we were excited to see a message,” Armbruster says. They could read most of it under regular office lights, and “It became even more clear when photographed and enhanced digitally,” Armbruster adds. Using census records, they found a George Smith living in Chicago at the time.

We don’t know what Dan and George(?) wanted to tell the future—but it’s clear they were happy for their message to stay high and dry.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook