Miracle Towns: Where Plastic Junk Becomes Holy Relics

A shrine to Mary (Photo: Dennis Jarvis/Flickr)

In the early 1920s, not long after people started making pilgrimages to the tiny town of San Giovanni Rotondo in order to see Padre Pio, higher-ups in his order of Capuchin friars tried to have him moved.

In 1918, Pio had been praying when a vision of wounded Christ appeared to him, and he was left with visible stigmata—bleeding wounds in his hands, feet and side—that would remain for fifty years, until the end of his life. In the wake of the Great War, wounded soldiers and other believers began hearing of the stigmatic priest and traveling to see him, at the friary where he lived, on the spur of land that juts out of Italy’s east coast. Within a year, San Giovanni Rotondo was getting hundreds of visitors each day.

Padre Pio’s growing magnetism spooked those in power: the Vatican did not recognize his miracles, and in 1922 forbade him from performing mass. The next logical move would have been a transfer. But the people of San Giovanni Rotondo would not let him go. In letters, leaders of the Capuchin order wrote that they feared an uprising in the region if the friar were to be moved. One local, after hearing a rumor that Padre Pio might leave, came to the friary with a gun, intending to kill Pio: “Better dead among us than alive for others!” he’s supposed to have said. And, once the transfer was canceled, the town’s civic leaders continued to defend him, even to push the Church to lift the religious restrictions on him.

“San Giovanni Rotondo quickly found out that it was a good thing to have him there, because they were really prospering,” says Michael Di Giovine, an anthropologist who has studied Padre Pio and written about The Seductions of Pilgrimage. “I don’t think the mayor who defended Padre Pio was simply fighting for the commercial interest of the town, though. There are people who saw themselves valorized by him. They thought: We have something extraordinary here. God chose us, fate chose us, and we are special.”

But, undeniably, being the home of a miracle maker—and, as of 2002, an officially recognized Catholic saint—has been good for the town. Miracles, by their nature, are not an industry that a town can buy into deliberately. But if a town can cultivate one and hit the right balance between the holy and the secular, miracles can be big business. But just having a miracle-inciting relic or Marian apparition is not enough. It takes more than a miracle to make a miracle town.

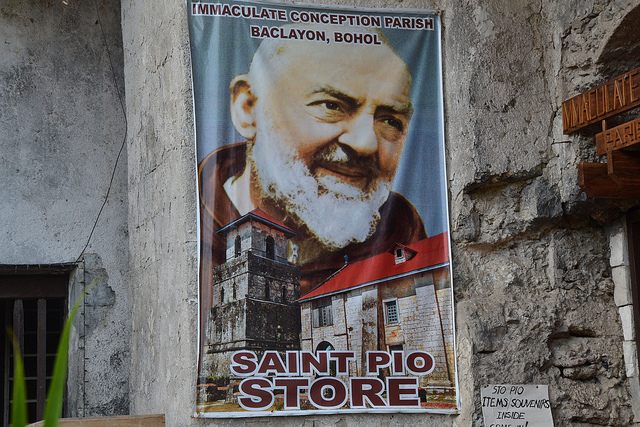

A store for Padre Pio (Photo: shankar s./Flickr)

There’s a real reason for an economically struggling town to try to milk a miracle for all its worth. Religious tourism generates $8 billion a year. Pilgrims need places to stay, eat and buy souvenirs to bring home, as gifts or as proof of their presence in a holy place. In Medjugorje, Bosnia, which became a site of pilgrimage after six children saw the Virgin Mary appear there in the 1980s, the town’s entire economy has come to depend on religious visitors, who come even though the Vatican has not officially recognized the apparitions and may soon announce that it does not believe them to be true miracles.

And some places do look deliberately to miracles as an economic development tool: one town in Bulgaria started building a new parking lot to accommodate visitors almost as soon as local archaeologists turned up bones they thought could belong to John the Baptist. “I’m not religious but these relics are in the premier league,” a Bulgarian minister told the Wall Street Journal in 2010. “The revenue potential for Bulgaria is clear.” (And Bulgaria doesn’t pin its hopes on only religious tourism: the more recent discovery of a possible vampire—a skeleton buried with a stake in his chest—also raises the prospect of a bump in visitors.)

These considerations, as well as souvenir shops hawking junky plastic trinkets and t-shirts, are hard to square with the divinity that miracles are supposed to represent. A miracle should be so awesome and so powerful that it’s undeniable—earthly considerations should have no consideration. But for a place that has come to depend on pilgrims, they have to.

“There’s a market,” says Ian Reader, a professor at Lancaster University who has studied pilgrimage in Japan for decades, and author of Pilgrimage in the Marketplace. “Places go up and down in popularity. Accessibility and support structures are important. They make it much more likely that a place is going to flourish.”

This is not a modern problem: miracle towns have always had to pit growing popularity against maintaining sacred space. In the medieval period in Japan, for instance, “the biggest shrine had the biggest entertainment court and the most brothels,” says Reader. No matter what pilgrims did on their journey, though, they needed proof that they’d been to the shrine they were supposed to be visiting. That meant buying some sort of souvenir.

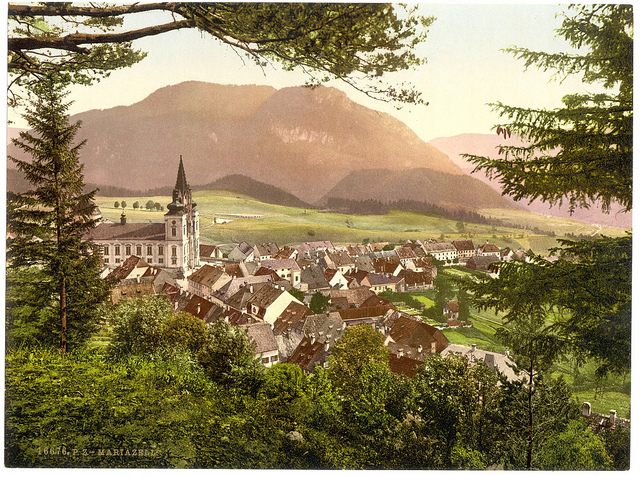

The commercialization of religious sites has reliably irked church and political leaders for centuries, too. In central Europe, in the late 1700s, Emperor Joseph II decided he “wants to shut down pilgrimage because it’s not happening for the right reason—people are going to get out of work or get out of supervision from their parents,” says Alison Frank Johnson, a professor of history at Harvard University. But when the emperor put a stop to this sort of observance, the loss of the pilgrimage trade was seen as a huge economic hit for the small Austrian town of Mariazell, one of the most popular pilgrimage sites of the medieval period (even if, as Johnson writes, it wasn’t the only cause of the town’s decline).

Mariazell (Image: Ashley Van Haeften/Flickr)

But miracle sites often do require deliberate actions to create or maintain their popularity. As Johnson writes in her study of Mariazell, in 1399, Pope Boniface IX “jolted Mariazell out of obscurity by granting the first plenary indulgence directed at pilgrims”—a boon that was shared at the time only by pilgrims to St. Mark’s in Venice. The Mariazell shrine, where an image of the Virgin Mary carved into a tree was believed to work miracles, was also favored by the Hapsburg dynasty, who, over their rise and rule, showered wealth onto the church and its town. In Japan, Reader found that priests at popular shrines would travel to other spots to scope out the competition. Or they’d ask: What’s playing well at the moment? What’s a popular thing?

The French town of Lourdes, where in 1858 a 14-year-old named Bernadette Soubirous saw a vision of the Virgin Mary, was supported by the Church. “In that period, in France, it wasn’t just Bernadette who saw the Virgin Mary,” says Reader. “There were lots of other teenage girls having visions in similar rural areas. One of the reasons why Lourdes was appealing to that Catholic Church was that the visions she had were quite optimistic. And it was very clear that she was a virgin.”

Infrastructure helps, too. In the past century and a half, as arduous travel has become less common, pilgrimages with better access to trains and planes have flourished while more remote spots have suffered. At Knock, in Ireland, in the years after a 1879 Marian apparition made the spot a pilgrimage destination, the parish had fallen into disrepair, and its popularity shrunk. But starting in the 1960s, a parish priest, Monsignor James Horan, pushed to revitalize the place, by building a new shrine and raising money to have an airport put in. The first flight went directly to Rome; there’s also a direct flight to Lourdes.

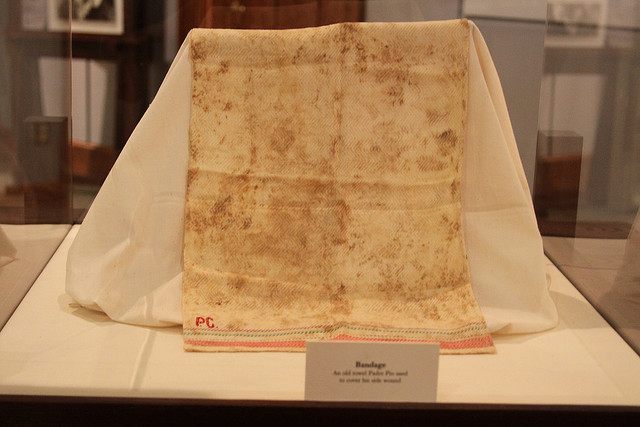

A bandage used by Padre Pio to bind his side wound (Photo: Jim, the Photographer/Flickr)

In the case of Padre Pio, his birthplace, Pietrelcina, has worked hard to capture some of the attention that the miracle site of San Giovanni Rotondo has enjoyed. At the turn of the century, the Catholic Church began considering Padre Pio for sainthood, which meant investigating every part of his life. For the first time, people started to visit the sleepy town in droves, and soon it became more popular as part of pilgrimages to San Giovanni Rotondo. The town has invested in its Padre Pio industry—in part because it’s been able to get grants to restore and maintain historical sites.

Pietrelcina only gets about ten percent of the visitors that San Giovanni Rotondo does, in part, Di Giovine says, because hotels in San Giovanni Rotondo sell all-inclusive room-and-board packages that encourage tour operators to make their stop-overs in Pietrelcina short. Because people don’t stay overnight, “the way they calculate how many pilgrims come to Pietrelcina is by how much trash is generated,” says Di Giovine.

This sort of deliberate development can go too far: there’s a tipping point at which a popular pilgrimage route, like Santiago de Compostela in Spain, can feel like a hiking trail. But it would be a mistake to think that just because there’s an economy connected to a miracle town, it strips the religious meaning away from the journeys people make there.

In her work on Mariazell, Johnson considered whether the development of tourist infrastructure and nature tourism would seem to be encouraging people to visit the site for the wrong reasons or if it would encourage them to come for what a pro-pilgrimage person would say were the right reasons. And she concluded that the two worlds, the religious and touristic, can co-exist.

“Mariazell is in a beautiful, beautiful spot,” she says, “and if you are a person who believes that pilgrimage sites bring you closer to God, and if you are a person who believes that nature brings you closer to God, there is something spectacular about a pilgrimage site nestled in the Alps. You can imagine you’re closer to the angels there than anywhere else.”

A rosary with Padre Pio’s image (Photo: the Italian voice/Flickr)

While living in Italy and researching Padre Pio, Di Giovine spent some of his time giving tours to pilgrims from Ireland, and he watched as they spent “hundreds and hundreds of euros,” amounts way out of proportion to their incomes, on kitschy things that might seen like junk. “They’re little images of Padre Pio, they’re plastic rosaries, and prayer cards,” he says. But what’s important is not the object, but what they do with them.

“They’ll go to this office, and line up. The priest who accompanies them will get a glove that the office has”—which Padre Pio would have worn to cover his stigmatic hands—“and they will line up and touch their tourist objects to them. They might be buying it from souvenir vendors, and they’re made in China, but to the pilgrims who buy them, if they touch them to the thing that has power, they are relics.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook