How America Fell Into—and Out of—Love With Mock Turtle Soup

The calf’s head concoction that once claimed American hearts.

In America in the 1860s, if you had something to celebrate, you might eat a turtle. That, at least, is what Abraham Lincoln did. At his second inauguration, in 1865, the celebratory meal began with terrapin as an hors d’oeuvre, probably boiled in a stew with eggs, cream, and butter. But if you couldn’t afford to eat turtle, or were in parts of the country where the reptiles were prohibitively rare, you might eat the next best thing: mock turtle soup. That dish was served at Lincoln’s first inauguration, when times were comparatively leaner. Diners would still have been happy; despite sounding like a joke at first, mock turtle soup was a comparable delicacy.

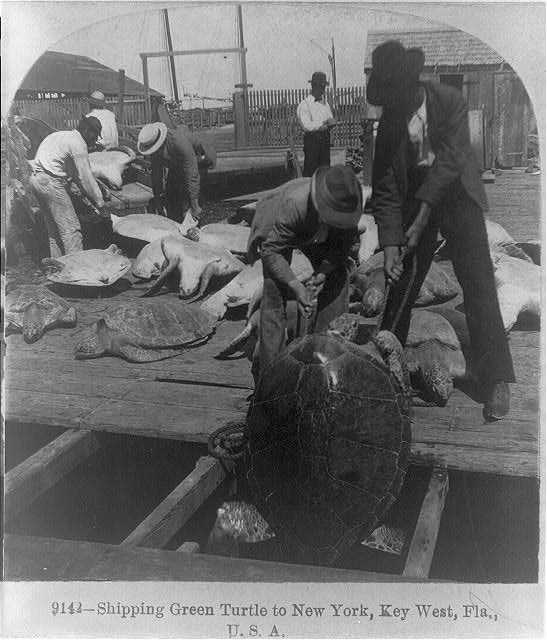

Wealthy Americans had a choice between the two—mock turtle soup for special occasions and real turtle soup for special, special occasions. The original chelonian stew had plenty of famous fans, including John Adams and George Washington. Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton were part of an elite dining group, the Hoboken Turtle Club, whose members came together to eat turtle soup with boiled eggs and brandy. William Howard Taft counted it among his favorite meals, and is said to have chosen his White House chef primarily on his ability to cook turtle. In the South, where turtles were abundant, wealthy Southerners turned out for massive parties known as “turtle frolics.” Saveur describes “servants bearing three-feet-long upturned turtle shells filled with hot turtle stew.”

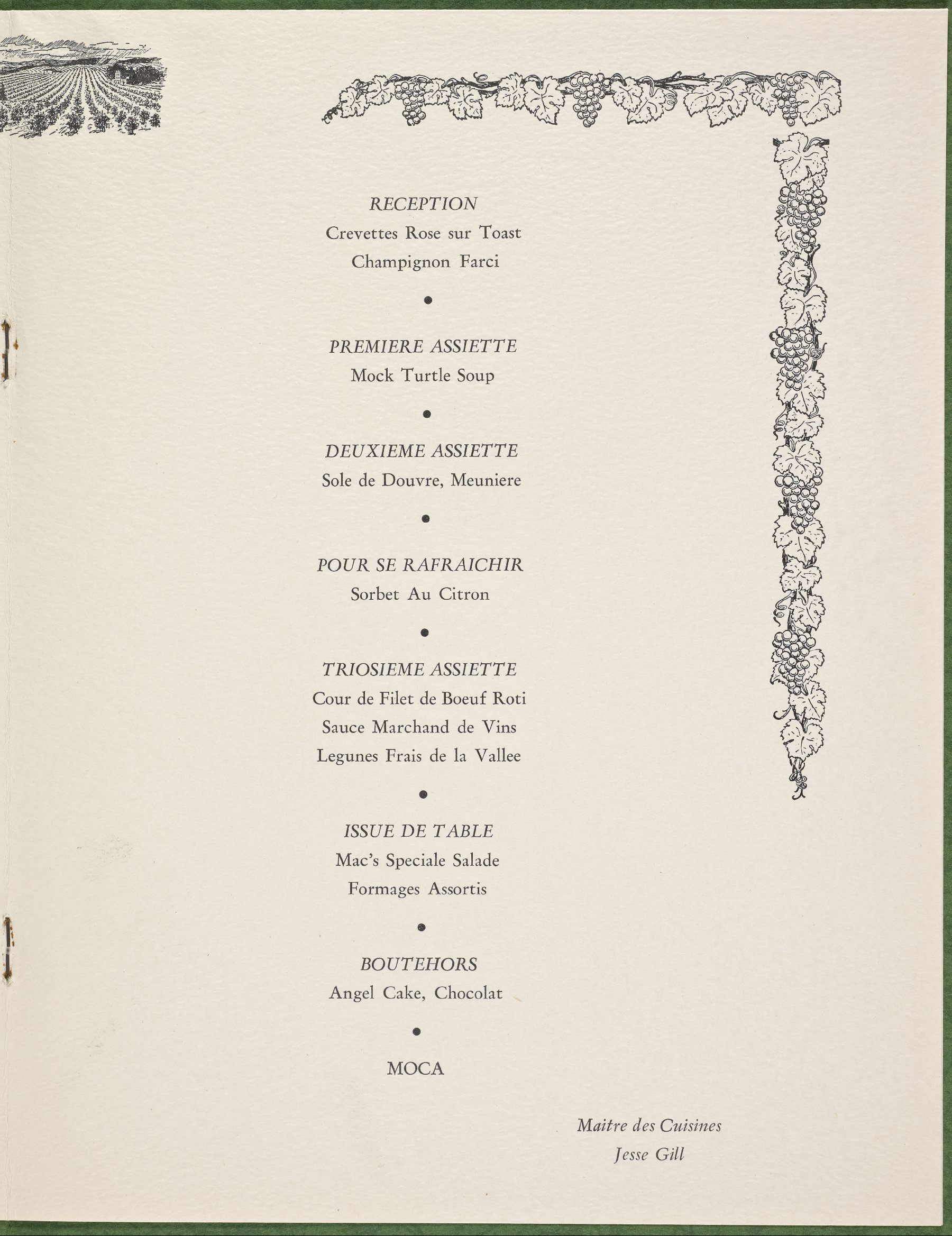

Mock turtle soup, on the other hand, was made with a whole calf’s head, which allegedly mimicked the flavor and texture of real turtle soup. Despite being made with a comparatively inexpensive cut that might have been discarded, it was still considered high-end, and was even erroneously described on menus as being French. It was priced accordingly: On Manhattan restaurant Sullivan’s 1900 menu, for instance, it is one-and-a-half times as expensive as any other soup. It was offered on upmarket tables at the Waldorf-Astoria, The Plaza, and the St. Regis, and in the pages of the White House’s 1887 cookbook, flavored with a medley of sherry, cayenne pepper, lemon, sugar, salt, and mace. There, it appeared right next to the recipe for actual turtle soup.

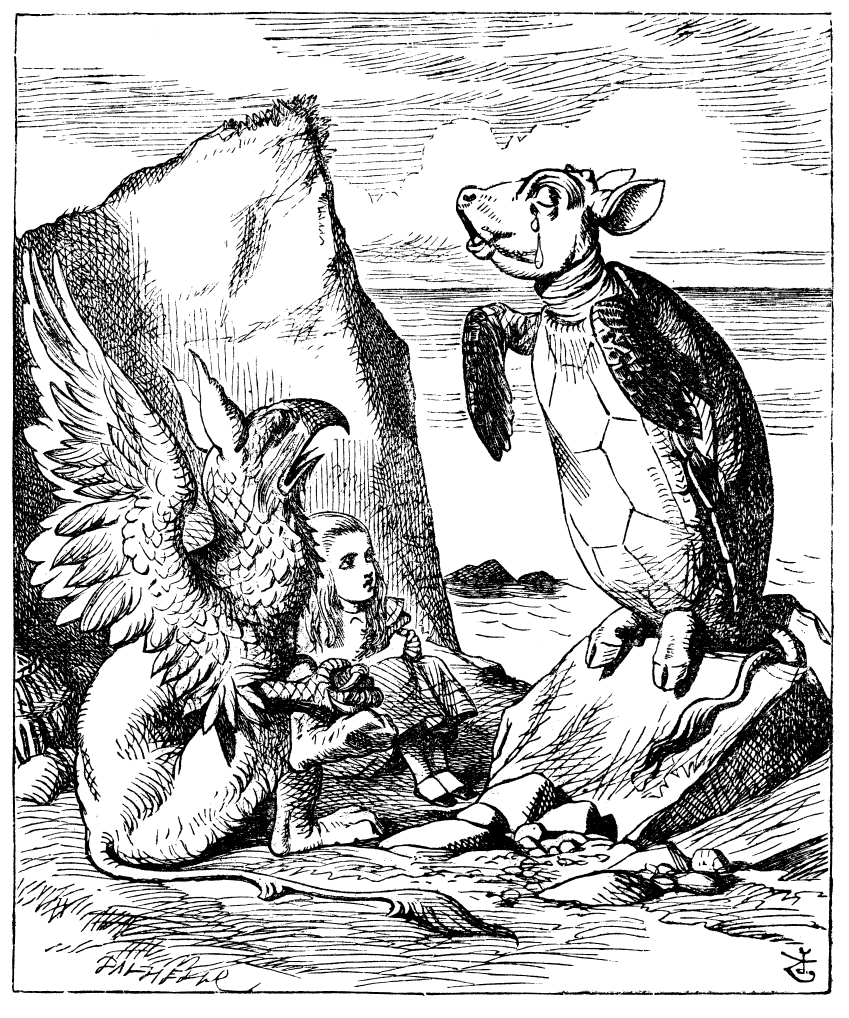

Like a cover song that eclipses the original, over time mock turtle soup became more popular than the real stuff. Children’s author Lewis Carroll played with the popularity of the dish in 1865’s Alice in Wonderland, with a character called the Mock Turtle. “I don’t even know what a Mock Turtle is,” Alice says. The Queen of Hearts replies: “It’s the thing Mock Turtle Soup is made from.” That thing, morose and weeping, has the shell and flippers of a turtle and the face of a lacrymal calf.

It is perhaps surprising that mock turtle soup became such a common sight on American tables, which had not been traditionally welcoming to offal. In the 1940s, when mock turtle soup was still on many top-tier menus, the American government struggled to find ways to persuade American diners to eat organs, heads, and other unidentifiable squishy bits. Chops, steaks, and other traditional cuts were being shipped overseas to feed soldiers and allies, and the American government saw hearts, kidneys, and brains as wasted sources of protein for the homefront. The challenge was how to persuade diners that they could be delicious. The Department of Defense even enlisted cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, along with food scientists and home economists, to draw up a new marketing campaign for offal, which they called “variety meats.” But by the time World War II ended, America simply went back to steaks and burgers, and continued to eschew (rather than chew) offal—except, for a while at least, for the calf’s head in mock turtle soup.

Even that didn’t last, though. The New York Public Library’s menu dataset shows that mock turtle soup was a popular menu item from the 19th century through to the middle of the 20th. By the 1960s, however, the only places with mock turtle soup still on the menu were the luxury passenger liner SS United States and Fort Worth’s Carriage House, a fancy French restaurant. Real turtle soup, on the other hand, appears on far fewer menus, but appears to have retained its cachet longer—appearing on SS Canberra’s Independence Day celebration meal as late as 1973.

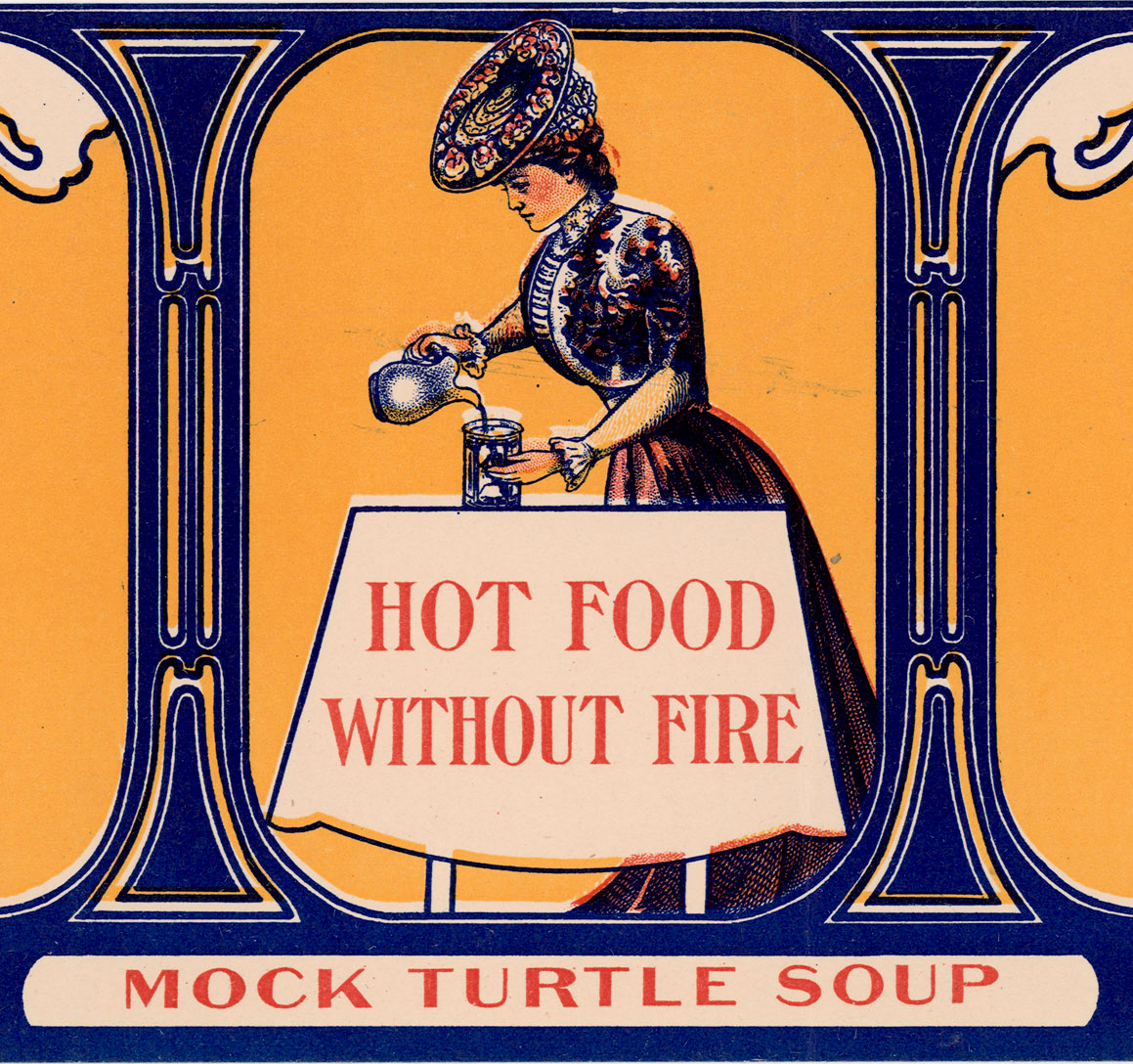

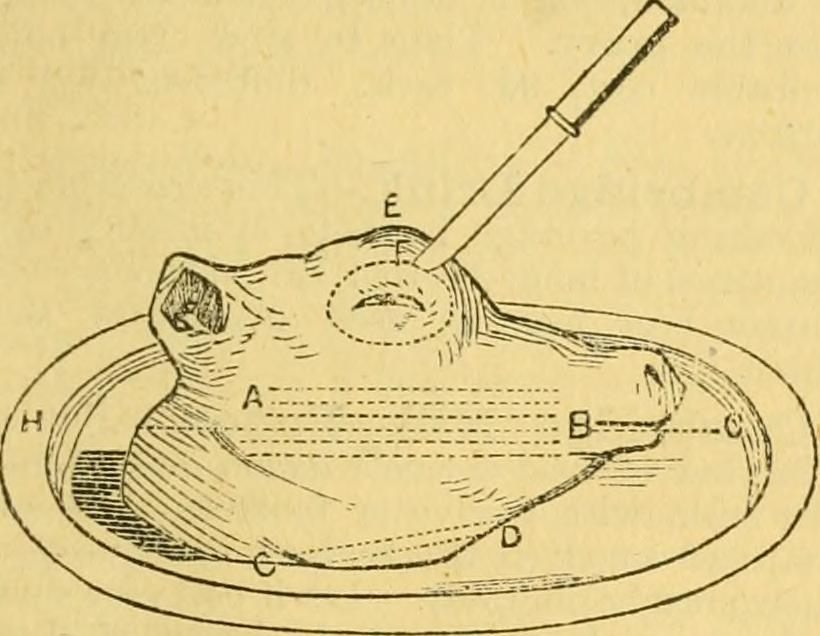

If mock turtle soup was more accessible than the real thing, it wasn’t particularly easy to prepare at home. The process of “dressing” a calf’s head began with opening the skull and extracting the brains, “face meat,” and tongue. From there, the meat needed to be boiled to tenderness before standing overnight. The introduction of a wider range of convenience foods in the 1950s—from frozen TV dinners to canned soup to dry mixes—sapped much of the energy for long days of standing over a smelly pot and even changed the American palate. “Millions of American palates adjusted to artificial flavors and then welcomed them,” writes Laura Shapiro in Something From the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America. “Consumers started to let the food industry make a great many decisions on matters of taste that people in the past had always made for themselves.”

Mock turtle soup did make the transition from arduous task to convenience food, but it didn’t stick. Campbell’s discontinued their Mock Turtle Soup—with its “tempting, distinctive taste so prized by the epicure”—before 1960. It didn’t have the range of fans that true turtle soup did, but Andy Warhol was among them. “I even shop around for discontinued flavors,” he told art critic David Bourdon in 1962. “If you ever run across Mock Turtle, save it for me. It used to be my favorite, but I must have been the only one buying it, because they discontinued it.”

There is one place in the country where the love of mock turtle soup never went away—Cincinnati. This enduring popularity may come from the German immigrants who made the city home in the 19th century. According to Cheri Brinkman, author of the Cincinnati and Soup series of cookbooks, Germans appreciated the soup’s “sweet-sour” taste. “With the major slaughterhouses of the Midwest located here at the time, there were plenty of calves’ heads available to make the soup,” she adds.

Today Cincinnati chefs make the dish with ground beef rather than offal, but it’s just as popular as ever. “It is still made by many local restaurants and at church festivals,” says Brinkman. Homesick Cincinnatians can even order it in cans: Local company Worthmore has been producing it commercially for over 90 years, with a recipe that includes hard-boiled eggs, lemon zest, and ketchup.

Real turtle soup is harder to get these days. Many turtles are endangered or rare and the demand for soup made from them is simply gone. Bookbinders Specialities, the canning off-shoot of famed Philadelphia seafood restaurant, no longer sells it in cans (“Snapper Soup,” they called it), though a few cases linger on Amazon. Purchasers complain, however, that it doesn’t taste like it used to. “The liquid in the can was a dark brown color and authentic Snapper soup has a dark brown color,” writes Amazon reviewer James A. “That sadly is the only valid comparison one could make between the two.” Worthmore’s mock turtle soup, on the other hand, is more highly regarded. Reviewer Clair Dohner puts it rather directly: “Worthmore canned Mock Turtle Soup is better than Bookbinders canned Snapper Soup.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook