La Patasola Is the Vengeful Protector of the Andes

And a scary lesson on humility and respect for the natural world.

Atlas Obscura and Epic Magazine have teamed up for Monster Mythology, an ongoing series about things that go bump in the night around the world—their origins, their evolution, their modern cultural relevance.

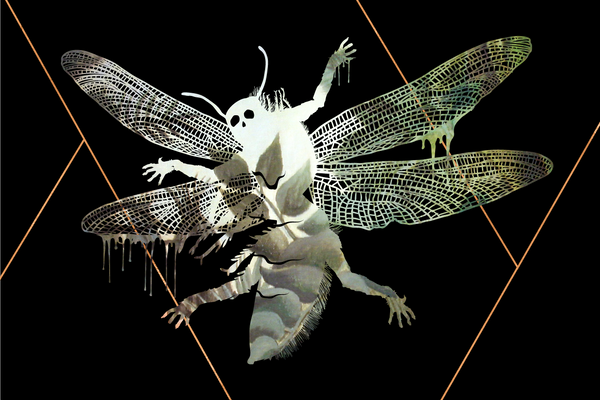

Imagine you are on your own, deep in Colombia’s central Andean region. Perhaps you are cutting down lumber in the lush forests, or prospecting for gold and platinum in valley creeks. Making camp at dusk, amidst the cooing of rare birds and the crackle of a fire, you hear a blood-curdling scream—unmistakably human. You set off through the dark forest to help, and then encounter the source of the horrible wail: a beautiful woman, impossibly pale, standing alone in the wilderness. Approaching, you suddenly realize: She’s standing on only one leg.

It was your distinct misfortune to see La Patasola or, as her name roughly translates, “the one-legged woman,” and it would, according to legend, be your last sight. Though she appears in various iterations and under numerous names, La Patasola is a recognizable legend, from Colombia’s Pacific coast in the north to Ecuador in the south, with details of her appearance and deadly allure largely consistent.

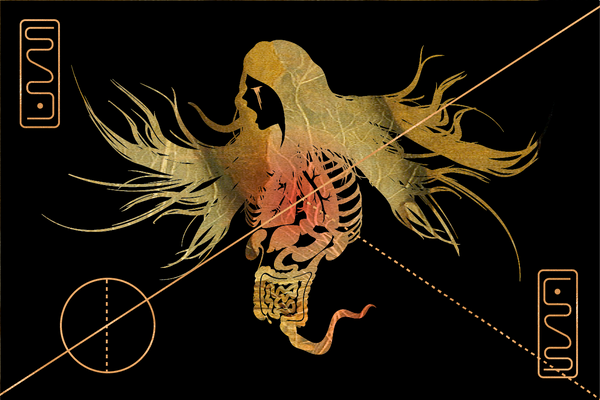

In some renditions of the tale, La Patasola is not merely a supernatural huntress, feasting on the blood of solitary men unlucky enough to encounter her, but also a tragic figure. In an account captured by the University of Southern California’s Digital Folklore Archives, Bogota native Ines Elvira Ortiz says La Patasola has vengeance in mind:

The Single Footed Woman was beautiful and she cheated on her husband, so he cut her leg off. She escaped into the jungle and swore revenge against all men. She appears in the nighttime, singing with a celestial timbre that captivates men, old and young alike. Sometimes, she screams for help so they come to save her. That’s when she traps them. She sucks out their blood and then she heads back into the jungle to hide.

There are few landscapes as ripe for such storytelling as the northern reaches of the former Inca Empire in which she is believed to dwell. Colombia, inhabited by at least 87 ethnic and Indigenous groups and enormously influenced by European and African migrants, ranks among the world’s few naturally “megadiverse” countries, as it is home to some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. Predictably, Colombia’s folkloric traditions—including the variations on La Patasola herself—are similarly rich.

“There’s no question that European elements have infiltrated and influenced and maybe combined with some of [her] indigenous elements,” says John McDowell of Indiana University’s Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. “In English, we might call her the old hag… She’s a female presence in the spiritual landscape. She’s very threatening. And she’s very widespread across much of the territory where I’ve worked.”

McDowell, in his extensive fieldwork throughout Latin America, has seen how the rich cosmologies of the Andean region actively invoke spirits, monsters, and destiny in the course of daily life. In this way, a run-in with La Patasola is not so much a matter of luck as fate. “The concept of accident really isn’t operative in some of these communities,” says McDowell. “Instead, [everything] happens for a reason. And the reason has to do with your spiritual protection, your spiritual health.”

In a world where personal misfortune can carry greater cosmic significance, La Patasola offers a lesson in humility and respect for one’s environment. Just as native cosmology imbues Indigenous Colombians with a deep respect for their surroundings, La Patasola represents a powerful and humbling protector of nature for modern times. The violent experience of European settlement and brutal violation of the rights of Indigenous people are reflected in La Patasola’s favored targets: lone men, usually seeking to despoil the landscape for their own gain. The lesson she teaches is what the Quechua people call sumak kawsay—roughly translated, “living in the correct way.”

“I’ve been involved in many storytelling situations where elder people were telling these mythical narratives, these stories of spiritual figures, to younger people around them,” says McDowell. “There is this sense that if we can steer our lives and guide our lives according to the example laid down in ancestral times, then we will be moving in the right direction.”

Through these tales, elders sustain customs and beliefs centered around harmony with the natural world. And these stories are warnings that persist, in part, because they are great fun to tell. “They create this magical universe where all kinds of incredible things happen,” says McDowell. “And you can see that most clearly in the trickster elements. All of the Indigenous people where I’ve lived—they love the trickster stories.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook