Did Humans Arrive in Micronesia Much Earlier Than We Thought?

Ancient sites such as Nan Madol, the “Venice of the Pacific,” may need to be reconsidered thanks to new evidence about sea level change.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Sea levels in Micronesia rose much faster over the past 5,000 years than previously thought, according to our new study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This sea level rise is shown by the accumulation of mangrove sediments on the islands of Pohnpei and Kosrae. The finding may change how we think about when people migrated into Remote Oceania, and where they might have voyaged from.

While recent decades saw significant advancements in linguistic, bio-anthropological, and archaeological research in the region, the exact pattern and timing of human settlement of Remote Oceania is still debated. Humans began migration into Remote Oceania—the area of the “open” Pacific Ocean east of New Guinea and the Philippines—some 3,300-3,500 years ago. This migration required formidable long-distance ocean voyaging of the likes never before seen in human history.

The region of Micronesia extends many thousands of kilometers and contains thousands of low-lying atolls. Many of these atolls formed roughly 2,500 years ago when the sea level in the region stabilized close to where it is today. Before that, the sea level might have been up to two meters (6.6 feet) higher than at present. People could only settle these atolls successfully once sea levels had lowered and stabilized.

But there are also older and higher volcanic islands in Micronesia. Across Remote Oceania, these higher islands were more desirable for settlement than low-lying atolls because they have more reliable freshwater sources, more developed soils for agriculture, and are less vulnerable to storm surges.

We looked at the published ages of settlement across the western part of Remote Oceania and found that high islands tend to show earlier ages of settlement compared to atolls, which is what we would expect. But we don’t see this pattern in Micronesia: The high islands of Pohnpei and Kosrae show settlement ages about 1,000 years later than other similar islands. Why?

Deep within the mangrove forests of Pohnpei and Kosrae, previous researchers found mangrove sediments up to five meters (16.4 feet) deep. The only explanation for such deep mangrove sediments is sustained sea level rise.

Mangroves live at the coast, between low tide and high tide. Therefore, as sea level rises, organic carbon and sediments accumulate beneath the mangrove forests, creating deep soils.

We visited the mangroves on Pohnpei and Kosrae and collected sediment cores to find out how old the sediments beneath them were. Our new data, as well as previous works, show that the oldest mangrove sediment is about 5,700 years old.

From this, we calculated that over the past 5,700 years, sea level rose by about four meters (13.1 feet). The most likely cause for this rise is that the islands are sinking: The land is going down relative to the sea surface. In our new study, we suggest this sea level rise obscured the archaeological record on Pohnpei and Kosrae. Consequently, evidence of earlier settlement—in line with other high islands—may be submerged today.

It is possible that people settled this region of Micronesia much earlier than previously thought, which also raises questions about whether people voyaged from the west or from the south to reach these islands.

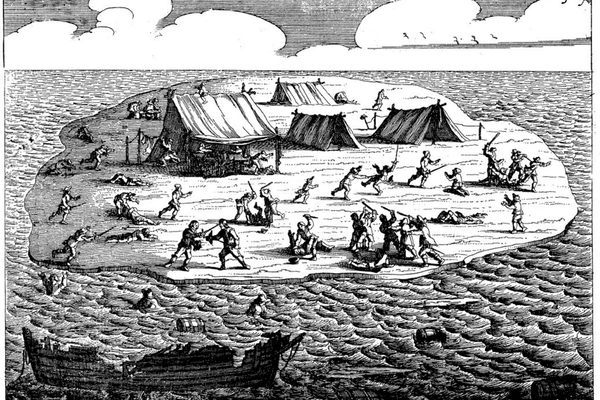

The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Nan Madol on Pohnpei may also stand as a testament to rising seas. Nan Madol is an impressive array of abandoned megalithic buildings constructed from dark basalt columns and crushed coral. This site has been dubbed the “Venice of the Pacific” because of the characteristic network of waterways around the buildings, resembling canals and islets.

Our record of sea level rise from the mangrove sediment shows that when Nan Madol was constructed (around 1180 to 1200), the sea level was nearly one meter (3.3 feet) lower than it is today. We suggest that it is unlikely Nan Madol was built with canals and islands in mind. Rather, the canals and islets are a result of sea level rise over nearly 1,000 years. Much like island nations today, large stone walls may have been constructed to protect the site from waves that were slowly encroaching higher and higher.

Juliet Sefton is an assistant lecturer at Monash University. Andrew Kemp is an associate professor at Tufts University. Mark D. McCoy is an associate professor at Southern Methodist University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook