In the Home of Japan’s Ice Deity, the Art of Kakigori Reaches New Heights

Inside one man’s quest to bring frozen glory back to Nara.

Nara has nothing delicious to eat.

At least, this is what novelist Naoya Shiga wrote in a 1938 essay about Nara prefecture, which he called home for 13 years. Although he then qualified this statement with some faint praise for his local tofu shop, readers latched on to the damning line, and Nara has since been burdened with a less-than-flattering culinary reputation, even among the locals.

To visitors, Nara is famous for the deer that roam its capital city, its ancient temples, and—to a certain subset of archaeologists—the kofun tombs, but not its food scene. The eponymous capital city is a popular day trip from Kyoto and most tourists tend not to venture beyond the circuit of large temples and shrines near Nara Kintetsu Station. When it comes to dining, they usually head back to Kyoto’s sophisticated kaiseki restaurants and matcha dessert shops instead of sampling Nara’s local specialties of kakinoha-zushi (persimmon leaf–wrapped sushi), sōmen noodles, and Narazuke pickles.

But if shaved ice makers like Sōsuke Hirai have their way, Nara’s kakigori—a Japanese shaved-ice dessert—will one day have its place on the country’s culinary map.

The eldest scion of a family-run, major kakinoha-zushi business, Hirai grew up immersed in Nara’s culinary world. And while the business was successful, Hirai was acutely aware that subtly flavored, humble fare like kakinoha-zushi appealed largely to gourmands looking for a taste of traditional homestyle Nara cuisine: Leaf-wrapped sushi and tea rice don’t exactly scream mass appeal. Even people from Nara believed their home had nothing to offer on a gastronomic front, something he was keen to change.

“They’re delicious, but kind of dull, which is fine, but they lack glamour,” says Hirai of Nara’s specialties. “Simply put, they’re not Instagrammable, and it’s not easy to appreciate their flavor.”

During his 20 years working in the family business, Hirai had long dreamed of creating food that Nara could boast about, but it became clear that it wouldn’t be leaf-wrapped sushi. Then, in 2013, he tasted kakigori made by Keiko Okada, a kakigori maker who would later become his business partner. Hirai saw immense potential in the mountain of ice flakes as a canvas for incorporating modern twists on Nara’s ingredients and traditional flavors. Okada would, for instance, sprinkle a freeze-dried powder made from local Asuka Ruby strawberries on milky-sweet ice, or turn a local roasted tea into a latte, reduce it to a syrup, and pour it over the shaved ice.

“Kakigori is incredibly easy to understand,” enthuses Hirai. “It’s gorgeous, it’s at once sweet and tart, and you can incorporate all kinds of textural elements, like crispy or fluffy things.”

In March 2015, Hirai and Okada opened Housekibaco, which serves an ever-changing array of intricately-constructed kakigori. These aren’t your average festival ices with luridly-colored syrups. One recent autumn creation: shaved ice layered with persimmon leaf tea syrup; caramel, honey, and milk syrup; chunks of poached persimmon; a heart of custard cream; and a crown of milk foam drizzled with more honey. In another, a center of pineapple cubes is surrounded by ice saturated with roselle (dried hibiscus flower) syrup, lemon syrup, and swirls of sweet-tangy cream cheese sauce.

Kakigori, Hirai believed, could become the Nara culinary sensation he’d been pursuing his whole life. There’s another reason that the shaved-ice treat felt destined for the region: Nara City is home to Himuro Shrine, Japan’s first and oldest shrine dedicated to the deity of ice.

Details of Himuro Shrine’s origins vary with the telling, but it’s widely agreed that it honors Tsugenoinagi-oyamanushi, a fourth-century man from Nara who invented a method of storing ice in a man-made himuro (“ice room”) to prevent it from melting in the summer. According to the Nihon Shoki, the younger brother of Emperor Nintoku encountered the ice-room inventor on a hunting expedition and subsequently introduced the ice-storage technique to the imperial court.

“Aristocrats back then used to put ice in their sake,” says Hirai. “It wasn’t something ordinary folk had access to.”

When the first imperial capital Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara City) was established in 710, a himuro was built on Mount Kasuga, and Tsugenoinage-oyamanushi was deified and enshrined there as the god of ice. The shrine was relocated to downtown Nara in 860.

Today, Himuro Shrine is mostly patronized by those in the ice industry, including ice manufacturers, kakigori makers, and bartenders. Every May 1, ice-makers gather for the Kenpyō Festival and offer two fish-filled columns of ice to pray for a long, hot summer and, by extension, good business. But Hirai wanted to bring a new demographic to the shrine. Inspired by the Kenpyō Festival and an event for kakigori makers held in Kobe, he approached the head priest of Himuro Shrine, Motohiro Omiya, with the idea of hosting a kakigori festival on the shrine premises. Thus was born the annual Himuro Shirayuki Festival, where famous kakigori makers from all over Japan gather and serve bowls of shaved ice to visitors.

Initially held in August, the festival now takes place around March, as the summer months tend to be busiest for kakigori businesses. Despite the cold weather, the festival has grown in popularity over the years, attracting around 10,000 people over two days at its peak (cold weather doesn’t deter true kakigori aficionados).

In addition to starting the festival, Hirai and other kakigori makers began publishing the Nara Kakigori Guide, a directory of local shaved ice shops, which they update with newly opened stores each year. The hope is that disseminating these guides will inspire “kakigori tourism” and encourage visitors to spend more time (and money) in Nara.

“Nara might be a tourist destination, but people usually spend just four hours here covering the most popular sights,” explains Hirai. “No matter how many visitors there are, money doesn’t flow into the local economy that way.”

The pandemic has meant that the festival has been put on hold for the last two years. In its stead, Hirai and Okada organized a small kakigori conference for makers from all over Japan. Participating businesses in places like Tokyo, Shizuoka, and Gifu also created special, limited-edition menus commemorating the festival.

Both Hirai and Omiya also hope that these efforts will shed light on and inspire support for the ice manufacturing industry. Most kakigori makers use either “pure” ice, which is artificially frozen over 48 to 72 hours or, less commonly, “natural” ice, which is slow-frozen in outdoor ponds over 10 days in the depths of winter. In both cases, the longer freezing process ensures crystal-clear blocks of ice, free of impurities—ideal for shaving fine, fluffy ice flakes. Although pure ice was once a staple for many businesses and households, the advent of mass refrigeration meant that demand for ice blocks has fallen dramatically over time. The ice industry at large has also been seriously affected by the pandemic due to many major summer events being cancelled.

“The number of companies that make pure ice is decreasing,” notes Hirai, who uses pure ice at Housekibaco. “In the past, even normal restaurants once used pure ice, but not anymore. These days, dry ice makes up the bulk of business for manufacturers, and it’s mostly kakigori makers and bartenders who really use pure ice anymore.”

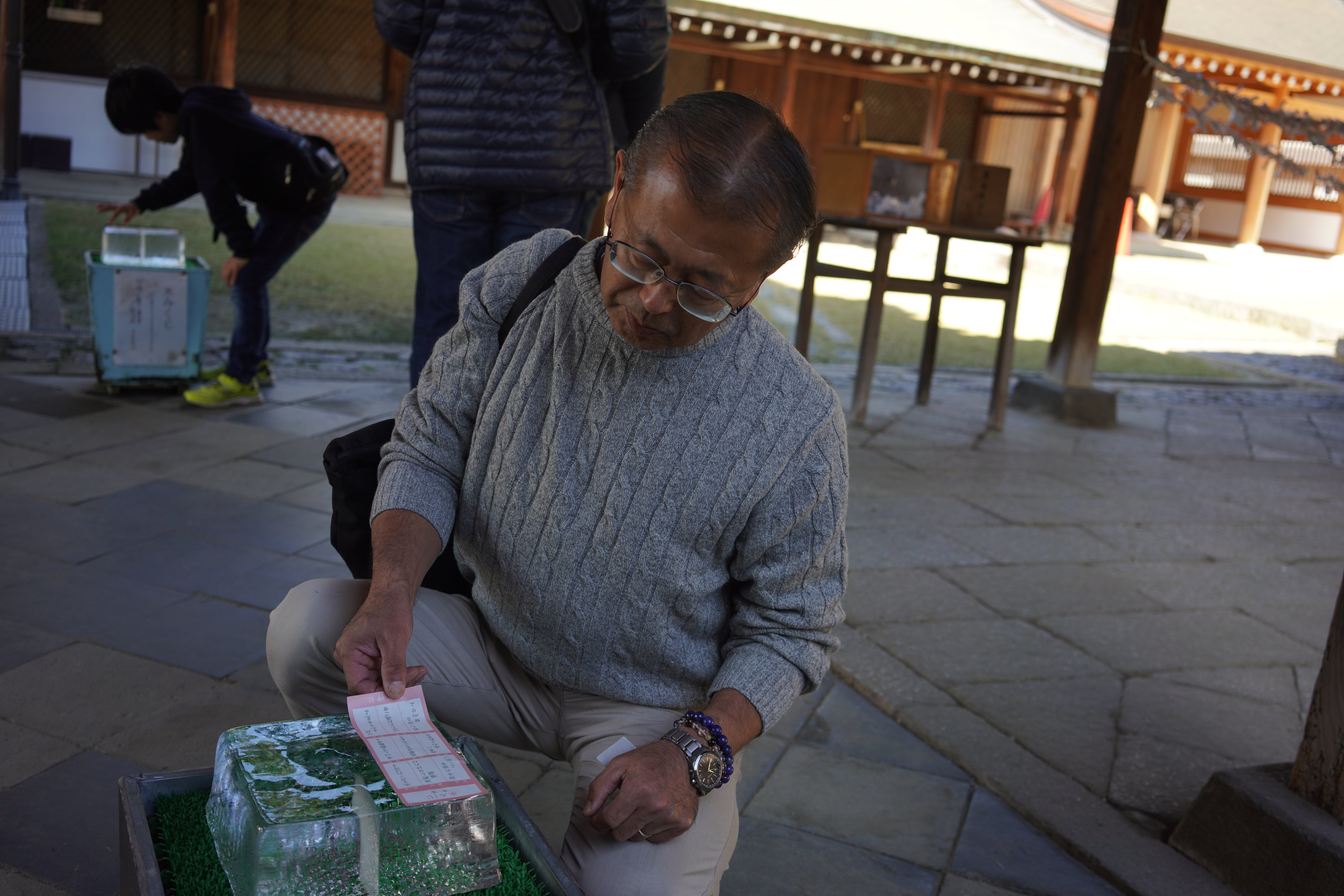

Naturally, Himuro Shrine also uses blocks of pure ice for various purposes. Visitors can purchase omikuji (fortune-telling paper strips), which reveal the fortunes only once they’re placed on the column of ice next to the shop. On the first and fifteenth day of every month, visitors can purchase cups of shaved ice and offer them in prayer before eating them; on these days, the shrine also arranges 200 ice lanterns—blocks of crystal-clear ice with votive candles set inside—around the shrine premises.

“We started doing this to highlight how good ice doesn’t melt easily, and also to pray for the continued prosperity of the ice industry,” says Omiya, whose family has overseen shrine operations since 1882. “I’d like to see other shrines do this too, but it costs a lot of money just to buy the ice.”

Pandemic notwithstanding, Hirai is optimistic that he will be able to resume holding the kakigori festival, and eventually have people associate his hometown with delicious kakigori.

“In Japan, when someone asks what they should eat when they go to Nara, everyone should be able to say, ‘Nara is obviously the place for shaved ice,’” says Hirai with a smile. “That’s what we’re aiming for.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook