Why North Carolina Is the Most Linguistically Diverse U.S. State

But it might not be that way for much longer.

Walt Wolfram grew up in a city so linguistically fascinating that the first time he met Bill Labov, the godfather of American sociolinguistics, Labov simply cornered him and made him say different words. Yet he left his native Philadelphia for a teaching job elsewhere—a place of even greater linguistic intrigue. “I got an offer I couldn’t refuse, Wolfram says, “to die and come to dialect heaven.”

Wolfram is coauthor of Talkin’ Tar Heel: How Our Voices Tell the Story of North Carolina, an examination of his adopted home, where he works at North Carolina State University (alongside his coauthor Jeffrey Reaser). He also happens to be one of the great American linguists of the past 50 years, with a specialty in ethnic and regional American English dialects. He has been a central figure in getting stigmatized dialects, such as African-American English and Appalachian English, recognized as legitimate language systems.

Wolfram has called North Carolina the most linguistically diverse state in the country, but that diversity is waning. The Tar Heel State is the intertidal zone of the linguistic South: Overwhelming forces wash in and out, but weird, fascinating little tide pools remain.

Language in the American South has gone through several sweeping changes in a relatively short period of time. But first, a little housekeeping—distinguishing an “accent” from a “dialect.” An accent is composed purely of pronunciation changes, almost always vowel sounds. Dialects, on the other hand, incorporate all kinds of other stuff, including vocabulary, structure, syntax, idioms, and tenses. The South has various species of both.

Before the Civil War, white Southeasterners did not seem to have spoken in what would be a recognizably Southern accent by modern standards. (There is some debate over this, but a 1997 study of uncovered interviews with Civil War veterans has become a major data point in Southern English history analysis, and indicates that this is true.) There were differences in the way people talked, but it wasn’t split as evenly along North/South lines as one would think. Southerners then, for example, seem to have had what’s called the “coil-curl merger,” which makes the “oy” and “er” sounds very similar. Think of calling a toilet a “terlet.” But that merger is also associated with an extremely non-Southern place: New York City and its old “Thoity-Thoid Street” accent.

Distinctly Southern dialects among the white population of the American South seem only to have taken hold starting around the time of the Civil War. (African-American and other minority dialects have their own histories, which will be addressed later.) “The things that we think are Southern today were embryonic in the South before the Civil War, but only took off afterwards,” says Wolfram. The period from the end of the Civil War until World War I—which seems like a long time, but is very condensed linguistically, less than three generations—saw an explosion of diversity in what are sometimes referred to as Older Southern American Accents.

In Southern states bordering the Atlantic Ocean, regional dialects sprung up seemingly overnight, influenced by a combination of factors including the destruction of infrastructure, the panic of Reconstruction, lesser-known stuff like the boll weevil crisis, and the general fact that regional accents tend to be strongest among the poorest people. In the post–Civil War period, Southerners left the South en masse; the ones who stayed were often the ones who couldn’t afford to leave, and often the keepers of the strongest regional accents. A lack of migration into the South, either from the North or internationally, allowed its regional accents to bloom in relative isolation.

This period of the South’s history spawned dozens of distinct dialects and accents, especially in the Atlantic states. World War II then began a series of events that pushed against these regional accents. Oil drilling, manufacturing, retirement communities, and military bases brought Northerners and wealth down to the South. “There’s been a lot of dialect leveling, that’s what linguists call it,” says Erik Thomas, a linguist at North Carolina State who often works on regional and minority speech.

When regional accents get leveled, they end up losing many of their distinctive elements—and essentially begin to sound more like one another. This is why old people from the South, especially anyone born before around 1930, sound different from young Southerners: They maintain at least the vestiges of the rich tapestry of Southern dialects. That’s all dying now. But it’s dying a little bit more slowly in some places than in others.

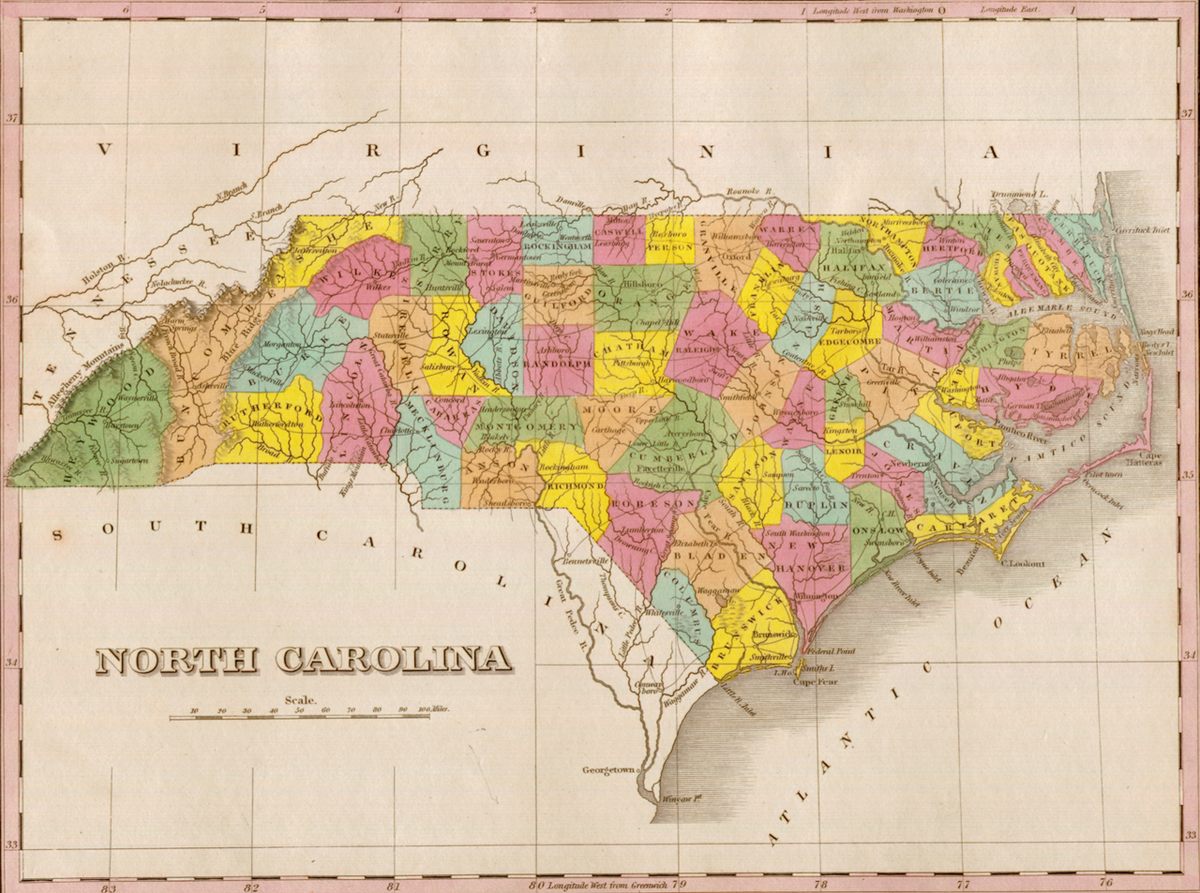

North Carolina stands out among Southern states for its tremendous geographic diversity. East of the Mississippi, there aren’t that many states with a substantial mountain range, a large plateau, and a long, island-pocked coastline. The ones that do, like New York, tend to exhibit an awful lot of different regional linguistic differences. And west of the Mississippi, there aren’t nearly as many of these differences among geographic regions within states.

There were many distinct regional accents or dialects in the pre–Civil War South, but some were more widespread (and better-known to modern linguists) than others. These include the Lowcountry accent near Charleston, South Carolina; the Appalachian accent, which ranges from Pennsylvania down to Georgia; the Plantation or Black Belt region, home to the richest soil and the highest numbers of slaves; the Cajun and Creole dialects of Louisiana; and the aristocratic Tidewater accent of Eastern Virginia.

North Carolina, smack in the middle of the Atlantic South, found more of those dialects within its borders than any other state. On top of that, North Carolina is home to a dialect found nowhere else in the world: the English spoken by those in the Pamlico Sound region, the coastal area that includes the Outer Banks.

Only a few generations ago, you could find an Appalachian speaker in the mountains of the west, a Tidewater speaker in the counties bordering Virginia, a Black Belt speaker in the eastern lowlands, and a Pamlico Sound speaker out on Ocracoke and Harkers Island, all without leaving the state.

These are dramatically different ways of speaking. Frankly, it would take too long to get into what makes them unique, but it’s easy enough to hash out a few of the best-known distinguishing features. Appalachian English often shows “a-prefixing,” as in “a-hunting and a-fishing.” The South in general tends to do what’s called a monophthongization of the long “i” sound. This turns vowels that are normally made up of two sounds—the vowel in a word like “spied” contains both “ah” and “ee”—and compresses them into one sound. Take these two words: “tight” and “tie.” In most of the South, that vowel sound is more like “ah” in the latter word. In Appalachia, it’s that way in both.

The Tidewater accent, a sort of upper-crust way of speaking, is best known for turning the vowel sound in “out” into “oo.” It is weirdly similar to the Canadian “oot and aboot,” though the southern Virginians and northern North Carolinians seem to have developed that on their own. They also have historically used the word “boot” for a car’s trunk and, amazingly, Wolfram says that one developed independently from the British, too. There are a couple of theories as to where “boot” in that use came from, but Wolfram suggests one in particular: that the storage for pre-car carriages was on the floor, next to a rider’s boots. Eventually any vehicle storage space came to be called a boot. Whether you’re in England or on the Virginia-North Carolina border, the nickname just makes sense.

The Black Belt accent is most similar to the Lowcountry accent of South Carolina. It’s known for British-y vowel sounds; “bath” gets more of an “ah” sound. It’s also a non-rhotic accent, meaning the “r” sound is dropped after many vowels: A word like “year” sounds like “yee-ah” (sort of like what a native Bostonian would say). One of the great examples of this accent can be found in the speech of late senator Fritz Hollings.

Then we get to the Pamlico Sound accent and dialect, which is the way people speak on the islands and, sometimes, mainland Hyde County. “It’s the only dialect in the United States that people routinely think is not an American dialect,” says Wolfram. The long “i” is changed, but not to a monophthong “ah,” as it is in the rest of the South. Instead it’s “oy,” which gives the people of Ocracoke and nearby islands their nickname: Hoi Toiders.

The speech of the Hoi Toiders sounds, upon first listen, closer to a Cockney or rural Australian accent than anything else in the South. It’s chock full of stuff that’s totally unlike any other American accent. “Fish” becomes “feesh.” The vowel in a word like “down” turns the word into something more like “deh-een.”

The vocabulary is also rife with local terminology. Vocabulary is not necessarily something linguists look at as a differentiating factor among accents and dialects, as unique words and descriptions pop into being and fade like fireflies, and aren’t always reflective of larger linguistic differences. But the Hoi Toiders have so many, and they’re so weird and cool, that linguists like Wolfram make sure to note them. These often come from the sea, as the life of a Hoi Toider revolves around boats, fishing, and marine weather.

“Mommucked” means to be extremely frustrated. A porch is a “pizer.” “Whopperjawed” means something is out of true. A “dingbatter” is a mainlander. And lest you think that all of these terms are straight out of Shakespearean English, that one comes from the early 1970s. Television first came to Ocracoke in 1972, when the show All in the Family was a huge hit. Archie Bunker used to call his wife, Edith, a dingbat, and the term ended up in wide use on Ocracoke to refer to the many tourists who didn’t know their port from their starboard.

These are all white accents, and North Carolina is, of course, not all white. The state is about 23 percent black and 15 percent Latinx, and has the sixth largest Native American population of any state in the country.

The idea that there are regional African-American dialects is actually sort of new to linguistics, likely due to the fact that the field has long been dominated by white, and often Northern, men. Hell, it’s really only in the past couple of decades that linguists have studied African-American English as a dialect, rather than as an incorrect or broken form of “standard,” white American English. There was, and often still is, an assumption among linguists that there is a homogeneous African-American English. Really though, there are simply some core African-American language features that span the country, and regional variations on those.

In any case, African-American North Carolinians seem to have a geographic division of dialects and accents, too. This video shows a substantial difference in vowel sounds between Appalachian and coastal speech, with coastal speech having some, but not all, of the Hoi Toider accent. Wolfram conducted experiments that found that listeners usually could not distinguish between old North Carolinians, regardless of race. Those same listeners, though, easily distinguished younger white from younger black North Carolinians, which is generally the case nationally as well. As with the other regional Southern accents, black North Carolinians are experiencing leveling. As white North Carolinians level to a way of speaking more like the rest of the white South, black North Carolinians are leveling to the black South.

A forthcoming book from Wolfram and Mary Kohn looks at regionality in African-American English, often using North Carolina as a base, and finds empirical differences by region. But there are so many other variables in African-American English: geographic region, urban versus rural, the stigmatization of black speech by whites, class differences, demographics—all kinds of stuff. It’s very complicated, and linguists are only now starting to try to unpack it.

The Latinx population in North Carolina is a more recent arrival, and faster-growing than any other non-white population in the state. The English spoken by native English speakers of Latin American descent in North Carolina is newish, but has the potential to become, or might already be, a distinct dialect. That long “i” sound in “spied” seems to be somewhere in between the sound in a Spanish word like “hay” and the flattened, monophthong “ah” of a white North Carolinian. There’s also a substantial overlap in language between Latinx and African-American populations in North Carolina, so Latinx speakers sometimes use what’s called the “habitual be,” as in “I be speaking.” It’s a form that indicates an ongoing action, and it’s heavily associated with African-American English. Latinx populations adopting African-American English features isn’t new, of course. It’s been well-documented in, just for example, the Puerto Rican population in New York City.

The Lumbee Indians make up the largest tribe east of the Mississippi, and mostly live in the eastern part of North Carolina. Wolfram has also studied Lumbee English, which sometimes has the Hoi Toider vowel change, but also comes with a series of vocabulary and grammatical distinctions. “Ellick” is a sweetened coffee, “juvember” is a slingshot, that kind of thing. What’s especially fascinating about the Lumbee population is that it’s so concentrated, which is extremely unusual for Native Americans in the Eastern United States. The small city of Pembroke is a whopping 90 percent Lumbee. That concentration functions as an isolating factor, and isolation is key for maintaining regional accents and dialects.

Basically, the Lumbee have sustained their regional accent in a much stronger enduring way than other populations. Ocracoke has a regional accent because it’s literally an island; Pembroke has one because it’s figuratively an island.

So North Carolina has a startling variety of American English dialects, including a couple found nowhere else. Yet, if you travel to North Carolina, there’s an extremely high chance that you won’t hear any of them.

North Carolina has the linguistic advantage of varied geography and a central location within the Southeast. But over the past 75 years or so, accents and dialects have been fading incredibly rapidly. Urbanization, an influx of new residents from other American regions and abroad, increased communication and national media, and improved infrastructure have all contributed to leveling throughout the South.

Today, the vast majority of the South sounds, largely, the same. The biggest split left is urban versus rural. Someone from rural Georgia sounds, for the most part, like someone from rural Texas, rural Tennessee, or rural Virginia. The cities sound like each other, too, and thanks to a greater flow of people, but then again Southern accents in cities have always been far weaker than those in the country. North Carolina is not exempt from any of this.

“The Southern-sounding accents have become more like each other, and in the cities they’re more like national norms,” says Thomas. The number of people speaking a Hoi Toider dialect on Ocracoke is down in the low hundreds. Good luck finding someone with a Tidewater accent who’s under 90 years old.

But a combination of geography, weather, and infrastructure have slowed dialect leveling in North Carolina a bit. “Before the 1920s, North Carolina had absolutely awful roads,” says Thomas. In the springtime, rains would turn the meager dirt roads into impassable mud pits. The Outer Banks relied on water transportation, isolating it from the mainland. Ocracoke still has no bridge. North Carolina’s Appalachian region is rugged and extreme, as distant from a major city as Appalachian West Virginia or Kentucky. That isolation has kept the local Appalachian English around, though it, too, is fading.

There are efforts to save endangered languages around the world, but dialects are generally left to mutate, merge, or disappear as part of the natural order of things. They are harder to get a hold of than distinct languages. Not all features are used by all speakers, the borders are fuzzy, the changes frequent.

“I’m one of the few people who says there’s no reason to exclude dialects from the endangerment canon, and there’s every reason to include them. They don’t much listen to me,” laughs Wolfram, who is trying his best to save or preserve the Pamlico Sound dialect. He has spent his spring break every year for the past 27 years teaching a class on it, on the island itself. “They’re interested,” he says, “but they’re not really saying they want to keep the dialect alive.”

Leveling has swept into the South like a tide. North Carolina has pockets that are hard for the water to reach, tidepools resistant to waves. But a roising toid is probably going to reach them, too.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook