Meet History’s Trailblazing ‘Only Women’

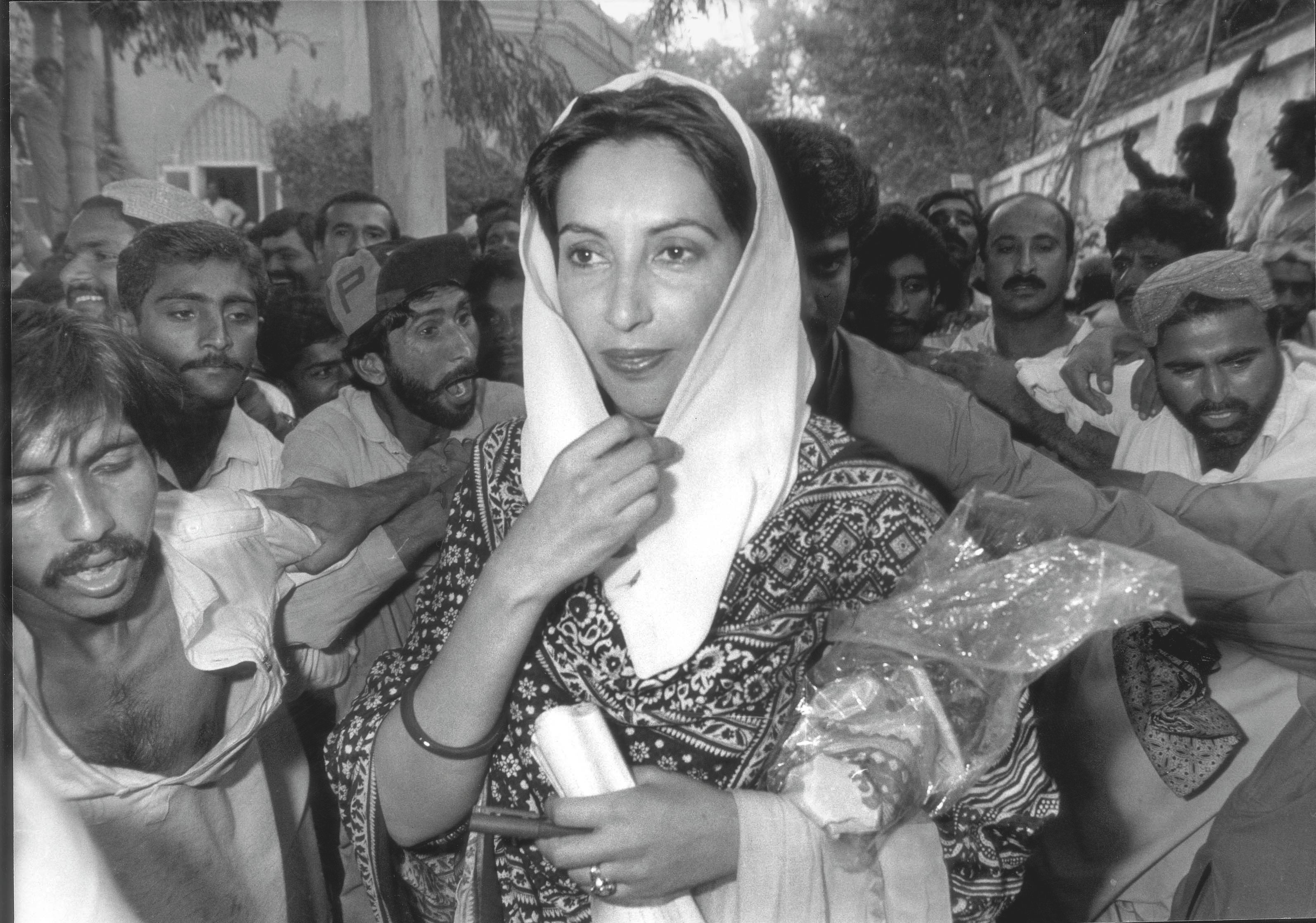

A new book features 100 striking photographs of lone women who broke barriers.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

There is a photograph of filmmaker Shirley Clarke taken in New York in 1962 that demands the viewer’s attention. Clarke, wearing all black, is surrounded by other independent and documentary filmmakers. She is in the dead center of the image, her eyes looking up, staring straight into yours. Her gaze is so powerful that you forget that amongst that group, she is the only woman filmmaker, a title she would carry for much of the 60s. For documentary filmmaker Immy Humes, this is the photograph that started it all.

For the past five years, Humes has been working on a film about Shirley Clarke, whose only full-length feature film, The Connection, was subject to several court cases regarding censorship in New York in the 1960s. But stumbling on this photo of her while doing research ignited Humes’ personal obsession with finding and collecting photos of what she calls “only women.” Humes’ years of cataloging culminated in her first book called The Only Woman, a compilation of photographs spanning time, space, race, cultures, and occupation, depicting lone women as they made their way into a man’s world. “I stare at them and wonder who these women are and how they felt and what these men think they were doing,” says Humes.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Humes about her interest in creating this book, how the concept of the “only women” opens up a conversation about representation and patriarchy, and what she hopes her readers will understand when they see these photographs.

What was the spark that made you think, I want to create this book about these women?

I was very shy about it, to tell you the truth. I had this collection of photos that was really interesting to me. Then I really started thinking, “okay, what is it? Is it an exhibit? Is it a website?” However, I knew that I liked the idea of holding the photos in your hands. And seeing the images as they accumulate? That, to me, was really important. So that meant a book. I was just very lucky because I had friends who pushed me to do it and helped me make it happen.

How did you find these images and how did you select the ones that are in the book?

It was really kind of a raggedy and long and fun process. I’m a research maniac so a lot of it was online; long insomniac nights, searching archives. I love archives because you never know what picture you’re going to run into. But it was also over time with other people who I know and love, saying, “oh, my God, I have a great one for you” and sending it over. It was also getting some from scholars.

Making the selection from the many hundreds was another part of the process. It had to be some combination of loving the pictures and making sure they had enough story behind them. I was also concerned that we understood that this was going to be my idiosyncratic selection, it was not going to be perfectly representative, or encyclopedic. It was going to be a little random.

In your introduction, you talk about your understanding of “only women.” Could you explain the different categories?

My basic thing was that every time you see just one woman, it’s not just an accident. So, once you have that, you start to notice these patterns. The biggest pattern is “the first”: So many women in this book, who are pioneers, were the first. t Then you start to look at them and start to realize, they actually are more than just “the first”. A first, to me, means that there’s going to be a second. So then you start to realize, like a lot of the first like Madame Curie, for example, were “the only”. In a lot of groups of men, there was a slot for one woman at a time.

Then there’s also what I call the “great exception,” whose extraordinary achievement brought them into these male societies. The “great exception” is this category that in a funny, paradoxical way confirms the rule that women don’t belong here. And we have the “mascot,” this figure who was the good luck charm to the group. It’s not like she has her own identity.

Finally, you’re gonna get obvious “tokens.” Tokenism, to me, implies being in a time and a place when the group wants to appear inclusive. It’s kind of semi magical. Having one woman is supposed to represent all women.

In what ways do you think that seeing these familiar photos spanning across time, space, race, and ethnicity, speak to a greater conversation about representation and patriarchy?

This is what I really hope that the reader will be thinking about. With the passage of time, we’re able to see it more sharply, with different understandings. This kind of absurdity is clear. I think each picture both shows the erosion of patriarchy and also the maintenance of patriarchy. What really struck me is how incredibly long lasting it is.

One hundred years from now, do you think these sorts of photos will still exist?

I do. There are many cultures where women do not participate in public life, and we presume that it’s a matter of time. But what do we know? So certainly, we’re going to see these pictures, because that’s what these pictures are about: women entering the public stage.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook