Protesters are Rebuilding Thoreau’s Cabin to Block a Gas Pipeline

Henry David Thoreau is helping fight big industry from beyond the grave.

Looking out on Ashfield from the inside of Will Elwell’s Thoreau cabin replica. (Photo: Will Elwell)

Standing by his new hand-hewn cabin frame at its dedication last month, Massachusetts resident Will Elwell proudly accepted the honorary name “Earth Badger.” Once home, upon a quick Google search, he found that badgers are small, ferret-like animals that mostly keep to themselves; however, when provoked, they have been known to attack creatures much bigger than themselves.

“I thought—wow, that’s perfect!” says Elwell. “I just try to stick to myself, but if you’re gonna try to come and, you know, bulldoze a pipeline through my town without me having any say about it, I’m not gonna sit there and let you do that.”

Neighborhood folks help Elwell raise the beams of the cabin. (Photo: Will Elwell)

Earth Badger Elwell, a timber-frame builder who lives in Ashfield, a quiet hill town of under 2,000 residents tucked among the farms and forests of the state’s western reaches, has been provoked, and by a daunting predator: the Kinder Morgan TGP Northeast Energy Direct pipeline. In response, Elwell has built a cabin—modeled after the one in which Henry David Thoreau lived and wrote his signature book, Walden—and has placed it directly on the path of the proposed pipeline.

The 416-mile pipeline would run through much of the local county, including some of the state’s most sensitive ecosystems, on its way from shale fields in Pennsylvania through New York state all the way to Dracut, Massachusetts. While it is unclear whether there is any regional need for the project (and there is evidence that the natural gas may be exported abroad), more than anything, locals are deeply distressed by the possibility of pipelines snaking through their peaceful backyards, in some cases just 50 feet from their bedroom windows.

Like many others, Elwell began by putting up signs, both in his front yard and along the highway—but within days, the signs had mysteriously disappeared. Elwell decided he needed to find a more effective way to express his opinion. The 67 year-old had previously been planning to retire from his career as a builder, and get back to working in his garden, when he realized, “Oh my god, I think I’ve got to do this—I’ve got to build a cabin.”

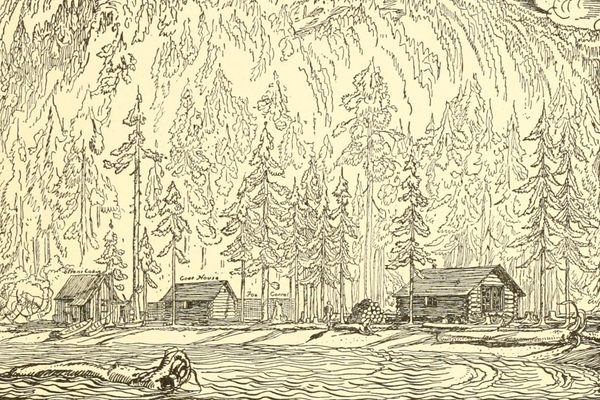

Elwell kicked into gear. He drove out to the Concord town library to find the blueprints of Thoreau’s original 10-by-15-foot cabin, where the writer, naturalist, and abolitionist penned his essays on nature and simplicity. He inspected its measurements, and then found timber left over from other projects, including some hand-hewn beams taken from a local 19th-century barn.

Though usually he employs a crew of five or six, Elwell spent three weeks chiseling the cabin’s bare-bone timber frame all by himself. “I wanted to do it just kind of as a meditative act,” he says. “Thinking about why I’m doing this, what I wanted to do, energizing it.”

The Thoreau cabin reconstruction at the Walden Pond State Reservation, on the original site. (Photo: Miguel Vieira/CC BY 2.0)

Though Elwell had grown up close to Concord, and often went fishing at Walden Pond, he’d never really thought much about Thoreau. But he knew that Thoreau had written about civil disobedience, intertwined with philosophy, society, government, and nature.

“Thoreau felt that if the government is not taking care of those who it governs, then there’s a right for citizens to express their opinion about that,” says Elwell. “And also if they need to create some kind of civil disobedience to change things, instead of just sitting around and accepting the status quo.” Not that Elwell wanted to end up in jail—he’d rather be in his garden—but he felt compelled to make a statement. He made a Facebook page, naming it the Thoreau Cabin Pipeline Barricade; he didn’t really know where the idea was going, but he knew the Thoreau connection was important.

Elwell was right. The cabin as a symbol of community defiance and discontent has struck a chord with many, both near and far.

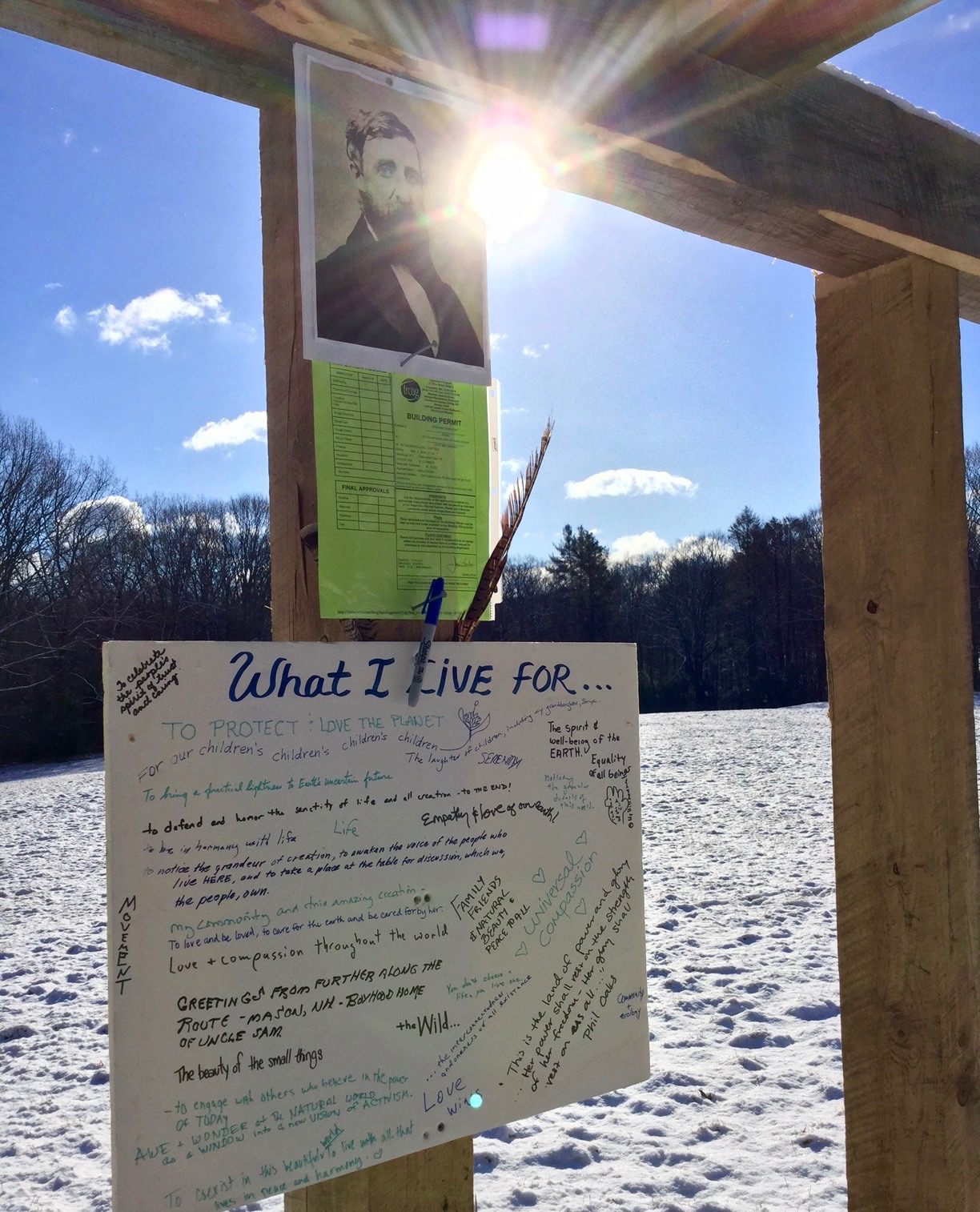

A portrait of Thoreau hangs above a building permit (by virtue of which the builders will be notified of any planned demolition). There is also a cabin journal, where passersby can leave any thoughts, quotes, or comments. (Photo: Will Elwell)

The cabin was erected in the field of Larry Sheehan, Elwell’s good friend and neighbor, smack dab in the middle of the pipeline’s still-invisible path. On a chilly day at the end of March, 150 people turned up for a dedication ceremony led by woman named Delta; it was here that Delta, who is of Native American heritage, gave Elwell the name “Earth Badger.” Pine boughs and cedar branches were placed on the top of the cabin’s frame, to commemorate the building and bless it with longevity, protection, and goodwill. Since then, others have come by to see the cabin, and Elwell has even pondered its potential as a center for education.

It’s currently up to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (DPU) to decide whether the pipeline serves the “common good” of the northeast. If FERC and the DPU give Kinder Morgan the go-ahead, Elwell envisions swarms of protesters descending upon the cabin, chaining themselves to its frame.

Elwell admits he’s not an expert on alternative energy, though he mentions solar, hydro, and electric as under-utilized options. In his mind, the pipeline seems to only bring liabilities—massive and noisy compressor stations, the potential for accidents and leakage, tainted water, and decreased land value. It feels like Kinder Morgan ends up with all the rewards, if there are any. “I hate to think of it as a reward,” says Elwell. “I just don’t equate rewards with any of this.”

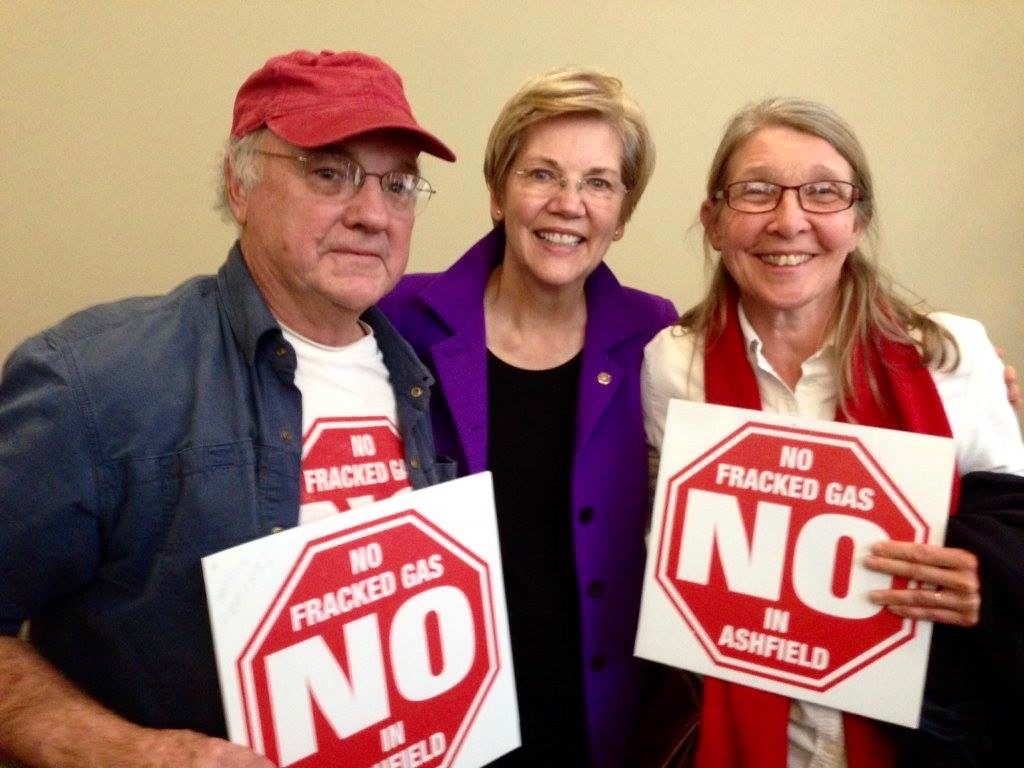

Elwell and his wife Donna posing with Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren at an event in Springfield, Massachusetts, where she came out against the pipeline. (Photo: Will Elwell)

Efforts, of course, don’t end with the cabin. Elwell and others are constantly on the lookout for other sources of leverage. Just the other day, he found a yellow-spotted salamander in his barn, and immediately thought: “Oh my god, maybe this is it, that can stop the pipeline!”

While it turns out the salamander is not an endangered species, there’s another creature that is: America’s beloved bald eagle. There have been local sightings (in 2015, researchers counted 30 eagle pairs in the state), and if one of their nests were to be found along the pipeline’s path, the game might be won.

Will Elwell standing in his wood frame cabin, in the early spring snowfall. He won’t be going anywhere. (Photo: Will Elwell)

So far, between America’s soft spot for Thoreau, our devotion to bald eagles, and Senator Elizabeth Warren’s recent anti-pipeline statements, things are looking up for those opposed to the pipeline in Ashfield and its neighboring towns. Compromise seems unlikely.

Elwell brings up a statement he made on the radio the other day. “I said you can take my signs, but you can’t take my cabin.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook