The Artists and Writers Who Fought Racism With Satire in Jim Crow Mississippi

How William Faulkner and a small group of provocateurs challenged segregation in ways that resonate today.

Early one summer afternoon in 1906, a crowd marched from downtown Oxford to the campus of the University of Mississippi to watch the dedication of a Confederate monument. At the top of the almost 30-foot-tall marble structure stood a Confederate soldier, facing the university’s main entrance, his left hand shielding his eyes from the sun and his right, at his side, around a rifle. The crowd, including Confederate veterans, huddled around. Ladies laid flowers. “The scene was an inspiring one,” the Oxford Eagle reported.

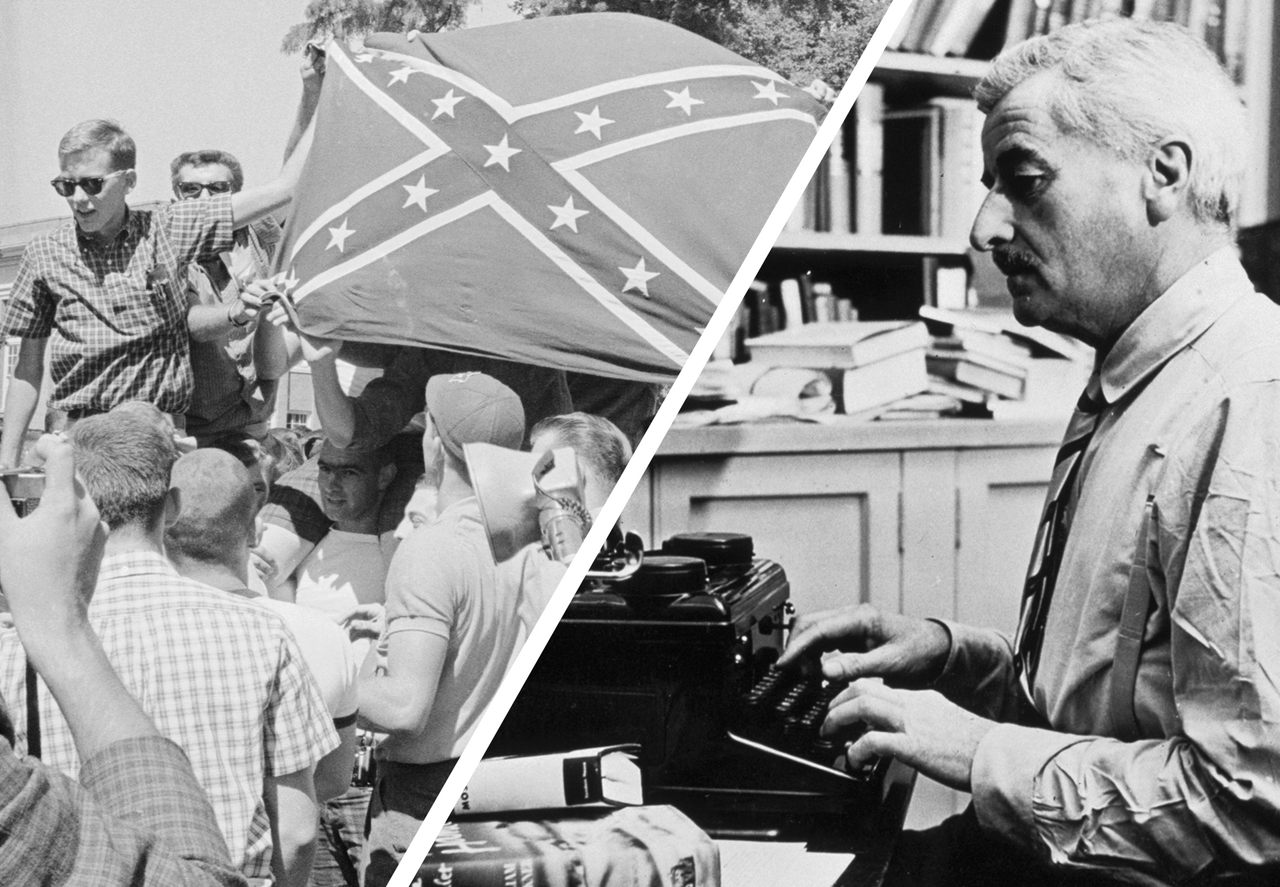

This past February, another group gathered downtown and walked to the monument, this time to protest the 112-year-old monument’s potential removal. Some waved Confederate battle flags, others the flag of Mississippi (the only remaining state flag to include the Confederate symbol). “This is an event to draw a line in the sand,” organizers wrote on Facebook.

Since the deadly “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, 50 Confederate monuments have been removed from public spaces across the United States, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. But this one still stands in the heart of the University of Mississippi campus—for now.

A growing number of people have been speaking out against the statue. Jarvis Benson, president of the Black Student Union, calls it “a stain on the campus” that “only continues to affirm the racist and hurtful ideologies of the past.” Cristen Hemmins, chair of a local Democratic Party, says it is a “rallying point for discord and hatred.” W. Ralph Eubanks, who teaches English and Southern studies there, describes the statue as a “monument to white supremacy,” one that “perpetuates a false narrative … that the Civil War was a noble cause.”

There are many who agree with opponents of the statue, but on a campus where more than 75 percent of the student population is white, in a state where 58 percent of voters supported Donald Trump in 2016, it is fair to call them a minority. Still they hold protests, conduct marches, occasionally address the administration directly, and write letters to The Daily Mississippian, the campus newspaper. “I cannot be silent,” Eubanks says, “when the truth is being silenced.” Their efforts are what led those Confederate supporters to campus in February.

This cycle of protest and counter-protest was almost unheard of a little more than half a century ago, when Mississippi was almost completely segregated. The 1954 U.S Supreme Court ruling that deemed segregated public schools unconstitutional led people across the state to form White Citizens’ Councils, white supremacy groups that still exist. “The South is armed for revolt,” notable Oxford resident William Faulkner said in a 1956 interview. “I know people who’ve never fired a gun in their lives but who’ve bought rifles and ammunitions.”

In that charged atmosphere, public opposition to white supremacy was rare and dangerous. But in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a small, loosely connected group on and around the University of Mississippi campus—Faulkner among them—raised their voices in opposition. But they could not do so publicly or directly. Instead, they used satire and art: clandestine newspapers that skewered the logic of segregation, oil paintings that put the vulgar language of racists into quiet, staid art galleries. These modest interventions caused a stir, and led to swift censorship and intimidation (including, in one instance, an arrest). The stories of how these artist-activists mocked, confronted, and exposed hypocrisy have faded through the years.

Real progress toward equality has been made at the university, and in Mississippi as a whole, over the last six decades, largely through the determination and sacrifices of African Americans—from the 2,500 who attend the university today to the countless others who are forced to obtain marriage licenses, register to vote, and visit courthouses in the shadow of the Confederate emblem. The white liberals of Faulkner’s day operated from a privileged, safe position, but their efforts reveal something of value: that the rejection of the South’s worst tendencies has roots in some of the darkest days of Jim Crow. These were some of the first homegrown public statements on an all-white campus to confront the intimidation of racists. The current push to have the Confederate monument removed is, in many ways, directly connected to that earlier effort.

“The cracks and fissures,” Eubanks says, “have existed for more than half a century. What we are witnessing now is those cracks getting deeper and some ideas crumbling.”

In spring 1956, about 2,500 students—every last one white—attended the University of Mississippi. (At the time, the schools that would become Alcorn State, Jackson State, and Mississippi Valley State Universities were available to African-American students.) According to a poll conducted by the student newspaper at the time, fewer than a fifth of the students believed African Americans should be allowed to enroll in the state’s flagship university. Among this minority was a tall, bespectacled freshman named Jean Morrison. Though he had grown up in Chicago, Morrison’s family moved to Mississippi when he was a teenager. At 19, he joined the Marines and fought in Korea. He arrived on campus in fall 1955 to study philosophy, a 22-year-old progressive veteran, out of step with most of his classmates. “Believe me,” John Rosenthal, a photographer who knew Morrison, says, “he was nothing like the kids in Mississippi.”

Morrison could be outspoken, and he was itching to make a public statement on race. He decided to create a fictitious, satirical newspaper warning of the dangers of allowing the “Scotch-Irish” into proper society. Of course, many white Mississippians are of Scotch-Irish descent.

Morrison recruited a few like-minded students, including Sylvia Topp, a 20-year-old Canadian liberal arts major. Topp, a writer who lives in Ontario, says that she had “barely seen a black person,” before moving to Mississippi. But after arriving in Oxford, she says, “I instinctively knew things were wrong.” She saw “Whites Only” signs on campus and in town, and black people stepped off of sidewalks when she approached. “Every day there was a new shock for me,” she says.

Morrison wrote many of the fictitious news reports, columns, and letters to the editor that appeared in the paper, all of which advocated for keeping the Scotch-Irish segregated from society. Topp designed the six-page paper, and the university’s chaplain, Will D. Campbell, allowed the group to print it secretly on a mimeograph machine at his church. “We worked all night in the church basement,” Topp says, “then distributed copies on the cafeteria tables very early in the morning.”

When students entered the cafeteria for breakfast that morning in February 1956, they discovered copies of The Nigble Papers. (Morrison came up with the name by combining a racial slur with “Bible.”) A note on the first page from the paper’s “publisher” explained that a member of the “U.S.D.S. (United Sons and Daughters of Segregation)” had recently introduced him “to the full power of the Scotch-Irish menace and its desire to overthrow our present system.” Included was a story about a “young Scotch-Irish boy” charged with calling a white woman a “wee bonny lassie.” A district attorney was quoted in it, saying the trial “may very well cast the dye—either for keeping our blood pure or for monegrelizing [sic] with the Scotch-Irish.” A letter to the editor asked: “I do not believe God wants us to mix with the Scotch-Irish, else why did he put them off on a little island by themselves?”

According to Topp, the paper was meant to “make other students think seriously about segregation.” The humor, however, was lost on most. Soon after the papers appeared, a group of students went to the dorm where Morrison lived and attempted to break in. When that failed, they painted white crosses on the doors.

“They had a near riot in the dormitory because of it,” the chaplain Campbell wrote to a friend.

Two months later, a second edition of The Nigble Papers appeared, touting the formation of a “Campus Conservative Club” because the “Scotch-Irish are getting the upper hand.” It included several fictitious book reviews, including one for Democracy and the Southern Way of Life, of which the anonymous reviewer wrote, “A stunning poignant essay on the difference between the two.”

“I wasn’t afraid at first,” says Topp. Some “football-type” guys began harassing her, laughing and sometimes blocking her way on campus. She wore knee socks then, and later a cartoon prominently depicting her legs appeared on a wall on campus. Soon after, she says, school officials told her to be in her dorm by 7:00 each evening. “I was surprised,” she says, “that the paper made people so angry, and shocked that the powers that be thought I was in physical danger.”

Meanwhile, university officials tried to figure out a way to deal with the paper. Morrison, in a letter to the student newspaper, accused a university employee of breaking into his dorm room and “capturing and destroying copies of ‘Nigble Papers.’”

He was referring to assistant registrar W.M. “Chubby” Ellis, who later wrote a “letter of concern” to the state’s college board, referring to the students behind the papers as a “Communist cell.” Of Morrison, Ellis wrote, “the editor of the paper publicly boasted before a group of students that he had dated negro girls in California, and that they were better than Mississippi girls.”

The board responded by writing that “every member of the university staff was concerned” after the first edition, but no rules had been violated. “After the second edition appeared,” the response read, “a regulation controlling such matters was drawn up at the university and approved by the Board of Trustees.”

That was the end of The Nigble Papers, but the fact that this tiny act of protest drew attention and action from the university’s highest levels represented an early crack in the facade of segregation. A few years ago, David Cox, another student involved, wrote on a blog that the underground publications did not accomplish much in the short term. “But I’d like to believe,” he added, “they helped in the long run.”

If nothing else, Oxford’s most famous resident noticed.

William Faulkner had spent that spring fitfully writing the novel that would become The Town. He was also concerned about the growing racial crisis in his home state. Faulkner, 58 at the time, supported integration, but he also feared that violence would follow if federal authorities tried to enforce it. Several times that year, he met with a small group of like-minded Mississippi residents. One was James Silver, a historian at the university with whom he sometimes played poker. Another was P.D. East, owner of The Petal Paper, a small, progressive newspaper in southern Mississippi.

One hot June weekend in 1956, at Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s Oxford home, they kicked around the idea of starting a moderate political party. Faulkner talked himself out of the idea, but when someone brought up The Nigble Papers, his interest was piqued, and the group decided to create something similar. If anyone was up for this type of humor, it was East, who routinely placed fake ads in his own paper poking fun at racists. One advertised two-by-fours that came presoaked in gasoline for Ku Klux Klan cross-burnings. He needled racists in more subtle ways, too. The name of James O. Eastland, the longtime U.S. Senator devoted to segregation, appeared in The Petal Paper as: “james o. eastland.”

East said he would take the lead on the paper, which the group named The Southern Reposure. Because Faulkner suggested they conceal their involvement, East dreamed up a fictitious publisher named Nathan Bedford Cooclose who, in a publisher’s note, described how he laid around in hammocks sipping mint juleps before dinner on his plantation. Faulkner seems to have contributed very little writing to the project, though East later confirmed that the Nobel Prize–winner came up with the paper’s lead headline: “Eastland Elected by NAACP As Outstanding Man Of The Year.” Most of the rest of the four-page paper consisted of edited versions of material from The Nigble Papers.

The publisher of a Gulf Coast newspaper agreed to print 10,000 copies of The Southern Reposure. In late July 1956, several hundred were mailed to specific people and the rest were sent to the state’s college campuses. East said he was told a faculty member at a private Baptist college ordered “that trash be gathered and burned.” Silver hid a mailbag full of copies in his basement, beneath a coal pile. Faulkner mailed copies to literary friends in New York, and at least one found its way to Harvard historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, who sent a check to help with the costs.

The plan was to publish The Southern Reposure twice a year, but no other edition ever appeared. Faulkner moved on, East had spent more than $300 that he could not afford, and Silver feared for his job at the university. (In fact, a few years later, when East published a memoir, he gave Silver an alias—“Joel Brass.”) “The fact that no second issue ever saw the light of day,” Silver later wrote, “convinced me that amateurs cannot sustain even the best of campaigns for long.”

By the fall of 1962, most of the people involved in making The Nigble Papers and The Southern Reposure were gone. Faulkner died that July. Campbell was in Nashville. East, tired of attempting to run a progressive paper in a conservative place, was preparing to leave Mississippi. Morrison was at Tulane University studying German literature and Topp had settled in New York. Only Silver remained.

The progressive historian had a new secretary that fall, Sarah Kerciu, whose then-husband was G. Ray Kerciu, an assistant professor of art from Michigan. The couple moved to Oxford in September. A few weeks later federal marshals escorted James Meredith, an African-American man, onto the university campus so he could enroll the next day.

“That,” G. Ray Kerciu says, “was when all hell broke loose.”

A group of 2,000 whites, many of them students, converged on the campus to block Meredith’s enrollment. Some gathered near the Confederate statue. Riots followed. Tear gas was deployed. Shots were fired. Two people—Paul Guihard, a French journalist, and Ray Gunter, a local—were killed. (Their murders remain unsolved.) Kerciu watched all of this from his office inside the Fine Arts Center.

“It was a bloody mess,” the 85-year-old says. “Every redneck from the state was there to fight the Yankee troublemakers, which I was one of them, I can proudly say.”

Troubled and inspired by the scene, Kerciu spent the rest of the semester producing a series of graffiti-style paintings that featured the Confederate battle emblem. He called one America the Beautiful, and on its canvas Kerciu painted some of the phrases he had heard or seen written on signs during the riots.

“Go home Marxist monster n*****.”

“A good n***** is a dead n*****.”

“Would you want your sister to marry one?”

Another painting, White Only, features those words superimposed atop several symmetrically arranged Confederate battle emblems. The following April, some of Kerciu’s work, including the Confederate paintings, was displayed in the Fine Arts Center.

“I hoped the paintings would make everyone on both sides think about the situation,” he explained at the time. “That was what they were intended to do.”

The majority of viewers, however, were not in a reflective mood. Several days after the exhibit opened, the university had five of the works removed. “Certain paintings have been taken by many viewers as indicating a slighting attitude toward the Confederate flag itself and all that it may mean to Southerners,” the administration said in a statement. Meanwhile, a law student filed state charges against Kerciu for “desecration of the Confederate flag.”

In an interview with the student paper, Kerciu pointed out that he did not make the offensive phrases up, he only presented what he had seen and heard. “As for the Rebel flag,” he said, “it was part of the atmosphere—part of all the statements that have come out. Now all the people seem unwilling to admit that they made these statements. It’s not my statements, it’s theirs.”

The next day, on April 10, 1963, a Lafayette County deputy arrested Kerciu on campus. He posted $500 bond and was released. He faced six months in jail. Over the next several days national media, including Time Magazine and The New York Times, reported on the situation. Novelist John Steinbeck sent the artist a letter of support. Malcolm X sent postcards that referred to segregationists as “Dixie rats.” Roughly a week later, the student who filed the charges withdrew them on the condition that the paintings never be displayed in the state again.

“I pulled out of Mississippi as fast as I could get out of there,” Kerciu says.

He moved to California, where he taught at California State University-Fullerton until his retirement in 2002. He figured the paintings would have lost their relevance by now. Then, in 2015, he says, “the Confederate flag reared its ugly ass again.” He was referring to images that surfaced of Dylann Roof following the mass shooting that claimed nine African-American lives in a South Carolina church. In the wake of that tragedy, Kerciu’s paintings were exhibited at the Laguna Art Museum in California.

“I never thought racism would still be around,” he says. “This new administration is bringing them all out.”

It is near impossible to find a copy of The Nigble Papers or The Southern Reposure today. The university’s Department of Archives and Special Collections has copies that can be viewed, but they are mostly collectors’ items. (A rare book dealer in New Jersey offers an original edition of The Southern Reposure for $1,250.) In 2004, Kerciu donated White Only to the University of Mississippi Museum. He does not expect it to be shown. He may be right: The collections manager says it is kept in storage and denies requests to view it.

Meanwhile, the days of a marble Confederate soldier standing armed in front of the university’s administration building appear to be numbered. In March, a few weeks after those Confederate supporters marched onto campus, the student body government voted unanimously in support of having the monument moved. The resolution, co-authored by undergrads, including Benson of the Black Student Union, calls for the statue to be placed in a nearby Confederate cemetery. “It detracts from the values of diversity and inclusion that are said to be so important to our community,” Benson says. “With that statue, those values are nothing more than talk.”

The university’s interim chancellor soon thereafter issued a statement saying the school would begin the legal process of having the monument moved.

Topp, now 83, says she does not remember the statue at all.

“I’m sure the idea of moving it would never have occurred to us, when segregation was a much bigger problem to object to,” she says. “I believe it’s up to the young people today to make this kind of decision. Kind of surprising that the vote was unanimous, though. Things have certainly changed from the ’50s.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook