Tips for Responsible Drinking, From 16th-Century Germany

The writer was concerned about the rise of binge-drinking bros.

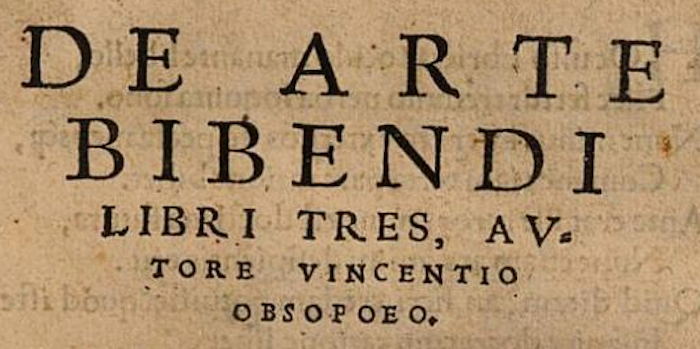

High school health classes, it turns out, have been around since the 16th century. That’s when a school rector in Bavaria, writing under the name Vincent Obsopoeus, published a poetic guide to responsible drinking, geared toward young men who—then as now—didn’t appear to know their limits. “Can it really be true?” asks “Drunkenness” herself in the book’s lyrical preface, written by a friend. “Should I really believe this book can teach people how to rationally lose control?”

Obsopoeus (pronounced “OB-so-PAY-us”) published this treatise, in Latin, in 1536. In April 2020, Princeton University Press published a new English translation by Michael Fontaine, a professor of classics at Cornell University. Entitled How to Drink: A Classical Guide to the Art of Imbibing, Fontaine’s translation speaks not only to the text’s historical moment, but to our very own, as alcohol sales have soared on account of the COVID-19 quarantine.

Nonetheless, says Fontaine, it’s important to read Obsopoeus with his time and place in mind. Though the popular imagination often pictures ancient Greece and Rome as decadent playgrounds of drunken excess, binge-drinking wasn’t actually culturally normative in those societies. For one thing, drinkers in those days tended to mix water with their wine. Moreover, their wine was less alcoholic than ours to begin with, as a lack of fungicides meant a shorter time for grapes on the vine.

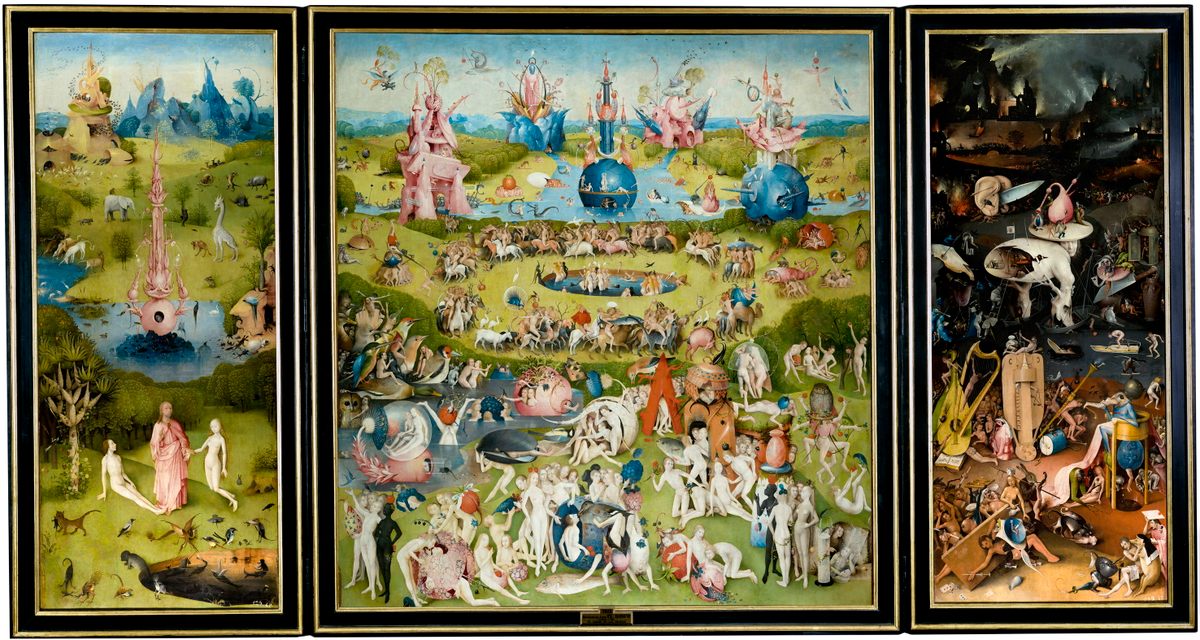

Instead, Fontaine writes in his introduction, “binge and bro culture—so familiar to Americans—started not in classical Greece or Rome but in Germany five hundred years ago.” The reasons, in his analysis, have to do with the end of the Crusades. Young men were still being educated and trained to become knights, but that path was becoming increasingly obsolete, and men began seeking other outlets for their aggression. It was in that context, he writes, that “hardcore drinking” emerged as “a mark of he-man prowess …” It didn’t help that vineyards accounted for four times as much German land as they do now. Even doctors and hospital patients were allowed to drink nearly two gallons of wine per day.

“At our parties,” Obsopoeus observed, “the host’s chief objective is to send his guests home hammered … From the get-go they’re pouring [wine] and playing competitive drinking games …” Next came his dreaded “beer chasers,” which the poet described as “an idea dreamed up … when the gods were angry.” Eventually “the soaked floor is drinking in a huge amount of wine. Rivers upon rivers are pouring down the tables; on more than one occasion, I’d have sworn the bottles were swimming.”

Obsopoeus wouldn’t stand for it. Channeling Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love), a series of instructional writings on the subject of romance, Obsopoeus sought to systematize the art of getting drunk—properly, respectfully, safely. (The Greek pseudonym “Obsopoeus” was another nod to the ancients, as well as an attempt to obscure his peasant German name, Koch; both translate to “cook.”) “Unless they worship [Bacchus, the Roman god of wine] with the precise art they should, those who worship Him will feel His wrath,” the poet warned. “Bacchus is mellow, you see, but if you underestimate His power and worship Him the wrong way, He becomes impossible to handle.”

As the poet saw it, moderation was good, including in moderation itself. He deemed some occasions, such as festivals, “suitable for overimbibing.” Much of his advice instead concerned the careful selection of drinking buddies. If “you’re going to drink wine and worship [Bacchus],” he wrote, consider “who you want to be with” (emphasis original). Find people with similar temperaments, in similar professions, people “who are tactful and modest in their language,” and “friends whose quality and loyalty are proven and unmistakable, time after time.” People, in other words, who won’t get goaded into a fight, who won’t cheat at drinking games, who would never let you get behind the wheel. It’s as if he was writing a script for freshman orientation.

Obsopoeus was also ahead of his time, says Fontaine, in paying close attention to the gendered dynamics of drinking culture. He was appalled by the drunken banter to which many men were and are prone—what gets called “locker room talk” today. “When guys are drunk,” he wrote, “they brag about their hard-as-wood erections” and “spill the beans about raunchy sexual bouts …” They become, he continued, “pigs full of snakes and lizards: they’re spewing snake venom from their mouths. Their venom’s more poisonous than that of a real-live viper … or a dragon.”

Fontaine points out that Obsopoeus—by repeatedly likening these caddish, intoxicated, peer-pressured exchanges to “venom”—was essentially identifying what we now refer to as “toxic” masculinity. The poet also mocked a drinking song that celebrated the carousals of germani. Fontaine notes that Germani means “Germans,” while germani means “brothers.” It’s as if Obsopoeus was calling out the drinkers for their glorification of “‘bro’ culture,” Fontaine writes.

The book concludes with a section advising readers who wish to succeed in drinking games. Yes, really. The poet’s main advice? Make sure everyone follows the rules: “You need to stay focused when you’re drinking,” he wrote. You must “keep an eye on what drinks you’re assigning each person and make sure your friend’s running the same race you are. I’m speaking from experience.” He continued, “nobody tells the truth when they’re drinking, and if you aren’t careful, you’ll get cheated over and over.”

All in all, it sounds like Obsopoeus would’ve made an excellent drinking buddy himself. After all, he literally wrote the book on it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook