This Award-Winning Australian Land Art Is Designed to Power 900 Homes

But will it ever be built?

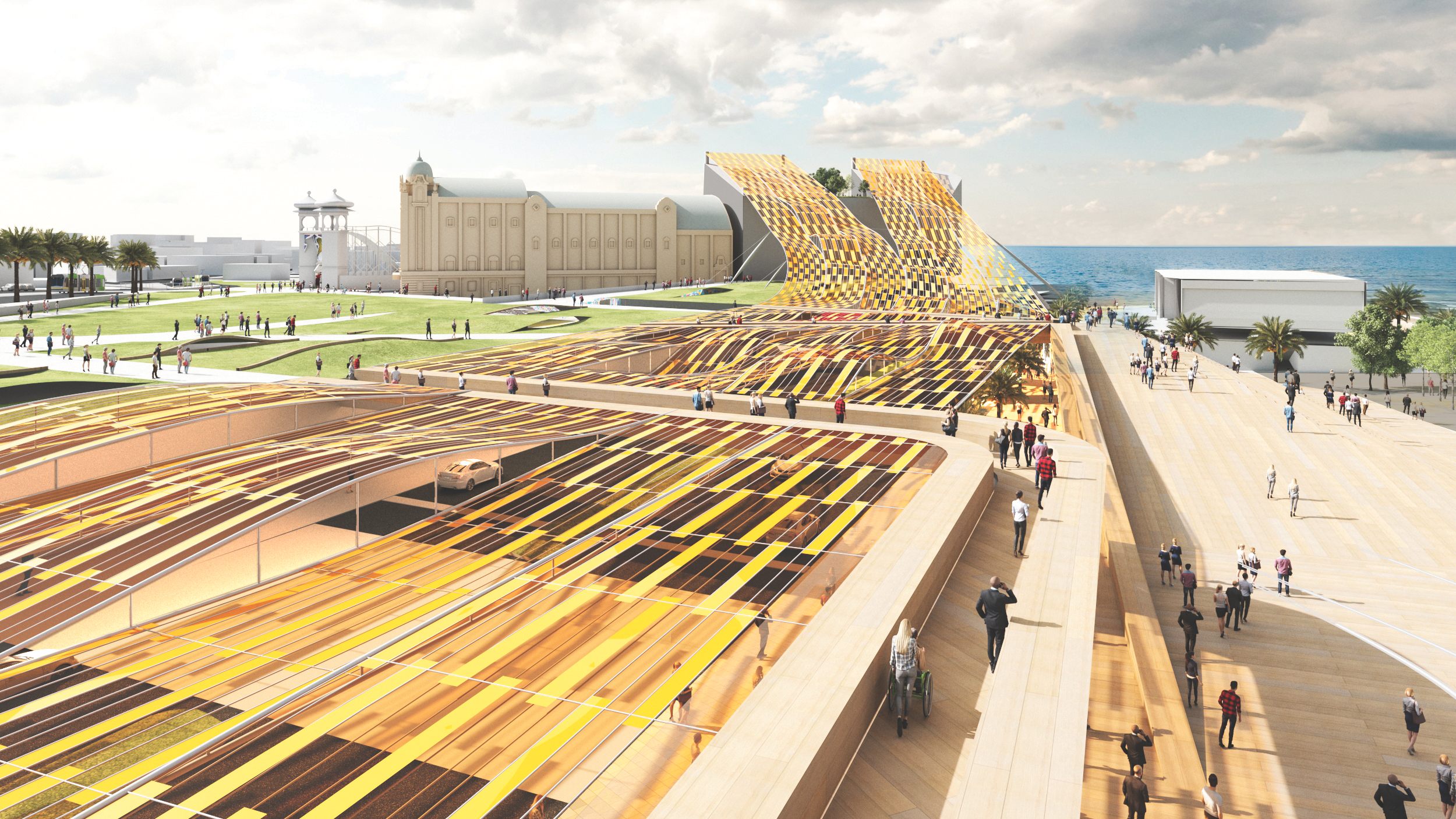

On October 11, the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), a biannual sustainable land art competition, announced its first-place winner for 2018. The victorious design is an energy-laced yellow canopy draped like a translucent racetrack across the sky, and intended to hover over a popular park in one of Melbourne’s major urban centers.

Every two years, the competition brings together teams made up of landscape architects, engineers, designers, and renewable energy advocates, who create hypothetical works of public art for a chosen city. The land art is intended to both beautify and power the urban environment, as a way to secure a cleaner future. After focusing on Dubai & Abu Dhabi (2010), New York City’s Freshkills Park (2012), Copenhagen (2014), and Santa Monica, California (2016), this year’s competition centered on Melbourne, Australia. Hundreds of proposals were submitted from more than 50 countries.

St. Kilda’s Triangle, a seaside Melbourne location with a rich yet somewhat indecisive development history, was the public space to be reckoned with this time around. The Triangle is surrounded by various cultural landmarks, the most notable of which is Luna Park, a fairground you enter by walking into the mouth of a giant angry face. This year’s winning public art proposal is called Light Up, a nod to the project’s promise that if implemented, it will illuminate 900 homes in St. Kilda, the Palais Theatre, and a newly redesigned public park and cultural center nearby. But the beauty of a proposal this strong and striking is really that it could exist beyond its assigned location and stare down climate change through its creative use of the natural world.

The first-place, Melbourne-based team made up of designers and engineers from NH Architecture, Ark Resources, John Bahoric Designs, and RMIT University made a point to make a Venn diagram of their expertise so as to not pigeonhole themselves in one particular strength. The result was a happy marriage of environmental empathy, smart engineering choices, and a bold but organic aesthetic.

Praised for its mix of beauty and practicality, Light Up’s design incorporates “solar, wind, and microbial fuel cell technologies to produce 2,220 MWh of clean energy annually for St. Kilda in the City of Port Phillip…this is buttressed with a nominal amount of energy harvested when wind blows across the swaying canopy, and from the roots of plants using microbial fuel cells,” founding LAGI co-directors Elizabeth Monoian and Robert Ferry say. Since energy storage is generally an issue with respect to renewables, “the design proposes to embed 107,000 used EV battery cells (from 50 fully electric cars) within the handrails of the bridge structures, conserving natural resources by extending the life of batteries that are no longer useful for cars.”

Pre-design, Mike Rainbow, a member of the winning team, says they visited St. Kilda’s Triangle to “understand the restraints” of their environment, which proved exciting because of the tense back-and-forth the community and state government have had over the public space: “It seemed like an opportunity to unlock a bit of an impasse between local government and the community,” says Rainbow. The team challenged themselves to “build something that was in and of the landscape as if it was intrinsic … so it wasn’t like you could pick it up and place it somewhere else because it was grounded in that local infrastructure.”

Perhaps more important than celebrating the great imagination behind Light Up, is navigating sustainability’s highly politicized status in Australia and finding a way to actually get it built. To date, no LAGI proposal—winning or not—has been fully realized. Rainbow laments this theoretical aspect of working in sustainable energy design and engineering. “That was something we wanted to break, we wanted to find a concept that excites LAGI from the artistic agenda, but that also excites potential stakeholders who would be able to help with funding and investment and those other attributes,” he says. “We were very conscious of delivering a design that we felt was going to be buildable and fundable.”

The initiative’s co-founders say that implementing proposals would require “partnerships between the energy sector, the city and state, community groups, and cultural institutions.”

Meanwhile, the world faces an increasingly desperate climate situation. In 2017, 1.4 percent more carbon dioxide was released globally than in the previous year, and the recent UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report recommended our world reduce 45 percent of carbon emissions by 2030 to reach net zero by 2050. The hope is that solution-based public artworks will swing the pendulum in the other direction. “Art has the power to create cultural transformations and cultural transformation will precede infrastructural transformation,” say LAGI’s co-founders. “So it’s time for creatives to lead the way.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook