Sardinian Carnevale Has No Place for Beads or Glitter

Instead it has animal skins, cowbells, bullwhips, and frightened children.

In a back alley of the bleached stone village of Mamoiada on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, a three-year-old girl is crying. Her mother kneels to comfort her. “There’s no such thing as mamuthones, ” she says. “There’s no such thing as monsters.”

The girl’s older brother shouts, unhelpfully, “That’s not true! I’ve seen them.”

The mother sucks her teeth dismissively. “They’re scary. But they’re only masks.”

The little girl uses her forearm to wipe her tears. “I don’t think you’re right,” she retorts. “I have seen them, too. There are men inside.”

In the region of Barbagia, deep in the island’s core, gray massifs erupt out of the earth on every side. The sun emerges late here and sets early, with pockets of light creeping and sweeping down craggy glens filled with prickly pear and wild fennel. The sweet-smelling valleys are studded with little medieval villages, largely unmolested by modern distractions, stuffed with men in caps and widows in mourning, and children playing accordions unironically in front of churches pockmarked by 10 centuries of wind and fingers.

Barbagia—first named that by the ancient Romans, who considered the locals to be “barbarians”—remains out of step with modern Italy’s bustle. Church attendance there is low for the otherwise hyper-Catholic country, even in the period approaching Lent, when the churches sit largely empty.

Carnevale—the last chance to eat too much, drink too much, dance too much, live too much—before the austerity of Lent is marked the world over by revelry and ribaldry: Think Brazil’s thumping parades, Venice’s masked pomp (though it was canceled this year), New Orleans’s gaudy spectacle. In Barbagia, beads and glitter are nowhere to be found. There are far too many cows to chop up and strangers to whip.

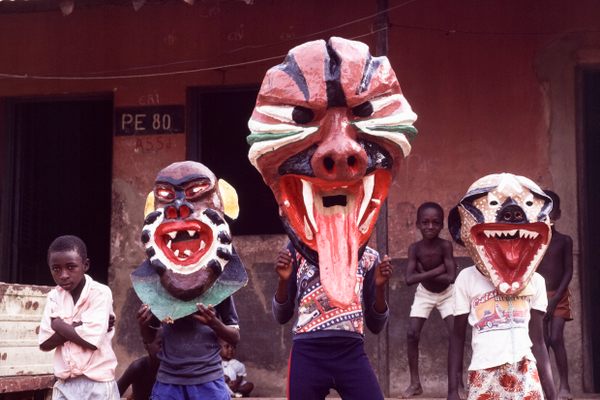

In this out-of-the-way part of an out-of-the-way island, for carnevale, thousands take to the streets, more in the spirit of the old gods, wearing grotesque masks and performing street dances while dressed in animal skins or covered head to toe in soot from bonfires. They scare children. They scream. They hit each other, and strangers, with whips. They draw crowds. They actually draw blood.

Sardinia has a long history of freedom from outside influence, and every village has evolved its own pre-Lenten code, each valley pocket of its own traditional dress, rituals, and masks. The two themes for the celebration shared across the region are cattle and bedlam. In Mamoiada, the little girl was frightened by the mamuthones, who wear pear-wood masks, animal pelts, and 60 pounds of cowbells, and create a racket in the streets as they’re led through by white-masked issohadores like cattle to slaughter.* In Ottana, the locals dress in bull head masks, and are accompanied by handlers called merdules who wear frowning black masks and animal skins that might be passed down from one generation to the next. In Lula, roving bands of men wear black cloaks, carry whips, and designate one person to be the official victim, or battileddu. This individual takes on the role of a freshly slaughtered cow and wears the dispatched bovine’s horns as his own, its stomach lining for a hat, and its steaming heart as a belt buckle. The rest of the band then drive the victim through the town with real bullwhips—while also taking swipes at both gawking locals and what few tourists show up, for good measure.

The festivities generally begin with a bonfire on the Feast of Saint Anthony, on the night of January 16. The macabre festivities then recur for a month of Sundays, culminating on the weekend before Shrove Tuesday, and then another bonfire and more revelry on the day itself. And when it’s all done, everyone goes home to take off their masks, wipe off the blood, remove the heavy weights, and wash the soot from their faces. The next morning, of course, is Ash Wednesday, when the rest of the Catholic world dons its ashes.

Additional reporting provided by B.A. Van Sise.

* The roots of the Sardinian carnevale practices are uncertain. Some sources have suggested that the black masks and smearing of soot on faces depict a local victory over Arab Muslim forces. Because this practice could be dehumanizing or akin to blackface, which has a history in the celebration of carnival in various parts of the world, we have updated the photos in this story.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook