The Schmaltzy Reality Radio Dramas That Heralded Courtroom Television

Hear “Mediation Board” and meet A.L. Alexander, the schlocky but sincere host.

Decades before Judge Judy ever slammed a gavel or Law & Order: SVU sped into its 17th season, people interested in the ins and outs of the legal system—or seeking a jolt of the maudlin or macabre—had the radio to turn to. These precursors to court shows and scripted procedurals offered nothing to see, but still delivered plenty of crackling drama.

In the 1930s in New York, listeners could tune in to WMCA to hear regular people like themselves pouring out their troubles in front of a panel of lawyers, on A.L. Alexander’s “Goodwill Court.” The verdicts weren’t binding, but the show was stuffed with sagas of marital strife and gambling debts—“all the little tragedies common to the average listener,” John Dunning puts it in On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. The broadcasts claimed to be a public service for poor New Yorkers who couldn’t afford legal services, even though forms of legal aid had existed in the city since 1876.

In a single episode, which varied in length from 30 minutes to an hour over the course of its run, the panel might hear as many as 15 grievances. Alexander, a former actor and divinity student, served as part-therapist, part-ringleader. He goaded the anonymous complainants and defendants, and was quick to swoop in when someone slipped into profanity or went too far with the details. When emotions ran high—and they often did, with participants’ voices cracking or thundering, by turns—Alexander played the foil. There was occasional silence—like when someone stormed out of the room, as they still do on daytime talk-fests—and Alexander let the dead air heighten the drama.

The show was a smash. It migrated to NBC, and almost immediately became one of the national radio network’s top-performing programs. That attention baited licensed lawyers, and the show was soon embroiled in legal woes of its own. Alexander was accused of swiping the name and concept of an existing, in-person, nonprofit program offered by a real Brooklyn judge. The New York Supreme Court forced the show off the air and discouraged lawyers from dishing out advice on the radio. (A bulletin in Broadcasting magazine also noted that an ethics board took issue with the fact that the legal advice was offered alongside Alexander’s sponsored pitch for Chase & Sanborn Coffee.)

Alexander took his trade to the pages of Redbook magazine, which was glad to make space for “the help and enlightenment of America’s Father confessor No. 1.” Still, radio listeners were hungry for what the show once gave them—insight into legal procedure and an invitation into strangers’ lives. Producers created other series with actors starring in recreations of mostly old cases.

Alexander launched a watered-down version of his program, called “A.L. Alexander’s Mediation Board.” The host (described by Time as “earnest, voluble, and begoggled”) convened panels of philosophy professors, priests, army generals—anyone he deemed a convincing moral arbiter. The committees then weighed in on everything from family tussles to romantic entanglements.

One episode was adjudicated—no joke—by a priest, a rabbi, and a university president. They started with Case 1438C: A man and a woman who had been together for 24 years and had raised eight kids without marrying. The panel had to decide whether it was time for them to make it legal. She wanted to. He didn’t understand why it was necessary. (He was a good father, he insisted. Besides, he said, there’s no such thing as love.) Alexander took it all very seriously. “Gentlemen, let us proceed,” he intoned, and invited each party to make a case. The woman demanded a binding contract. Her partner scolded her for a streak of independence and said he’d only agree to a ceremony “if she gets down off that horse that she’s riding.”

“You just have to compose yourself, I know that you’re terribly excited about this and you’re righteously indignant,” Alexander says as the man’s hackles rise. “Now let’s hear what these gentlemen have to say about the question of marriage.”

The panel took just seconds to side with the woman. “I would suggest that, as soon as possible, these two people have this marriage of theirs legalized,” the priest said. The rabbi agreed, and added that “the children may be stigmatized with illegitimacy” if the nature of the relationship goes public. “I feel sure that would be good in the sight of God and man,” the rabbi added. Case closed. Cue the swelling music, and on to another story.

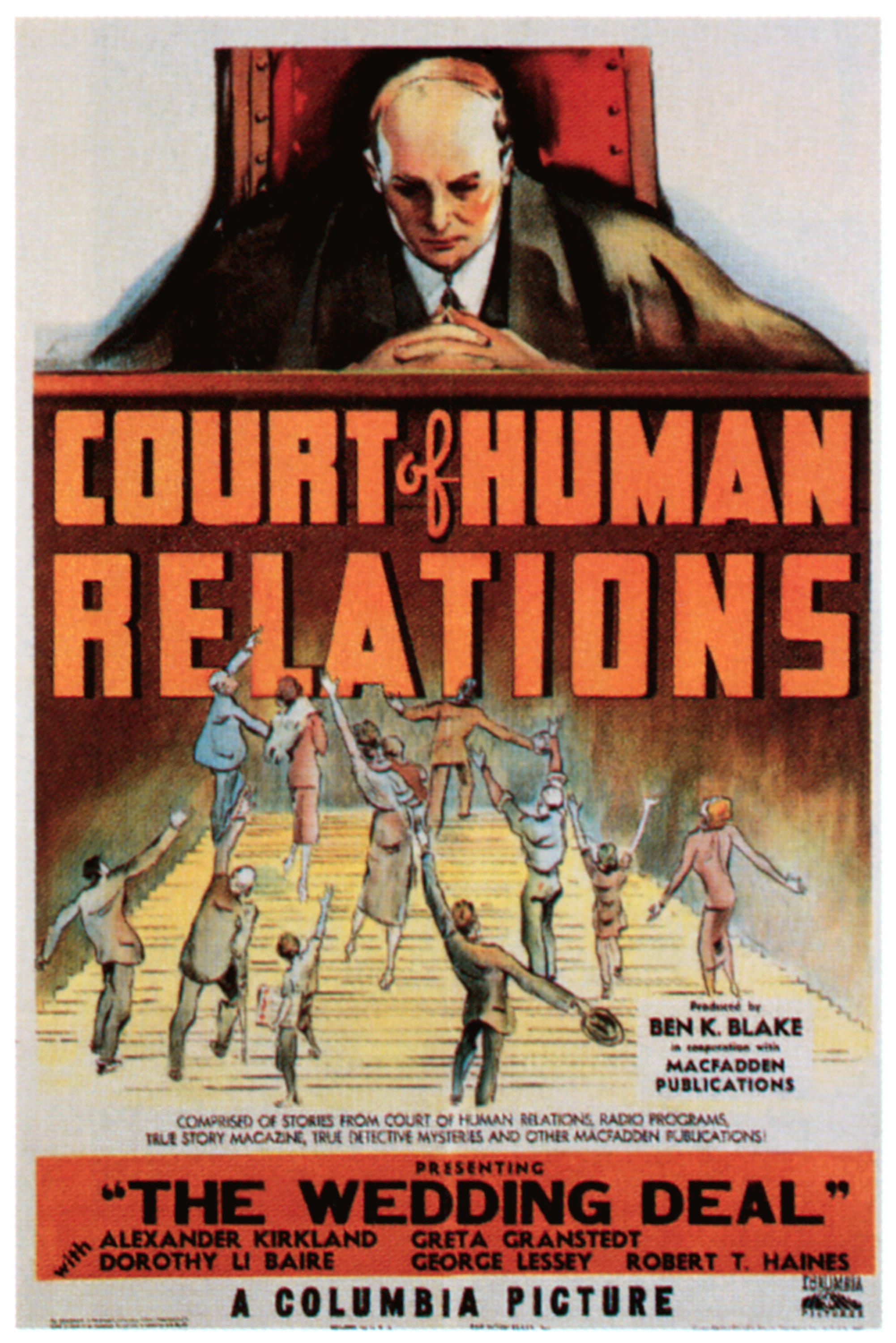

Versions of these radio programs eventually made the leap over to television. Alexander helmed “Court of Human Relations,” an adaptation of the radio roundtables. A week before its 1959 debut, the once-and-future host assured the Minneapolis Star that the television program was still rooted in hand-on-bible truth. “There are no scripts and no actors,” he said. “The actual parties in dispute will appear on the show.” If the content made one of the parties squeamish, he added, “we will arrange the studio lighting so that they cannot be seen.” The ultimate goal was “to operate within the bounds of good taste at all times.”

Upon first listen, Alexander’s earnestness feels put-on—the saccharine manner of a pathos-milker—but he appears to have been pretty sincere, or at least a deeply committed huckster. In 1941, a few years after his first show went dark, he compiled hundreds of pieces of verse into a guileless book called Poems That Touch the Heart. (It has gone through multiple printings.) In the introduction, he fretted over a crisis of empathy. “In the noisy confusion of today’s high-pressure world, against the great canvas of economics and politics and far-reaching world affairs,” he wrote, “there is a tendency to overlook the ‘abstraction’ known as the human being.”

The limits of science had been reached many times over, he continued. People could hurl rockets to the Moon, smash through the sound barrier, and split atoms. But they couldn’t seem to master the challenge of coexisting without treating each other terribly. “The most challenging—surely the most distressing—problem of our time is ‘man’s inhumanity to man,’” Alexander wrote. No panel of judges could make people more decent, but that didn’t stop him from trying.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook