The Delicate Art of Illustrating Ancient Sharks

Artist Aaron John Gregory balances scientific accuracy and creative flair.

Three hundred million years ago, long before the Discovery Channel invented the most successful marketing scheme in the history of television, every week was shark week. On the geological calendar, this is the Carboniferous Period, or, as it’s known to selachimorphaphiles, the “Golden Era of Sharks.”

It was a time of unparalleled marine diversity: big sharks, little sharks, spiral-jawed sharks, anvil-finned sharks. In books, on television, and across the internet, the Great White’s ancient ancestors are often depicted as more monster than fish, straight out of a scuba diver’s nightmare. But these pictures are, in fact, more aesthetic interpretation than perfect snapshot. They are works of scientific illustration, one of few professions where the austere rationality of science collides with an artist’s creativity.

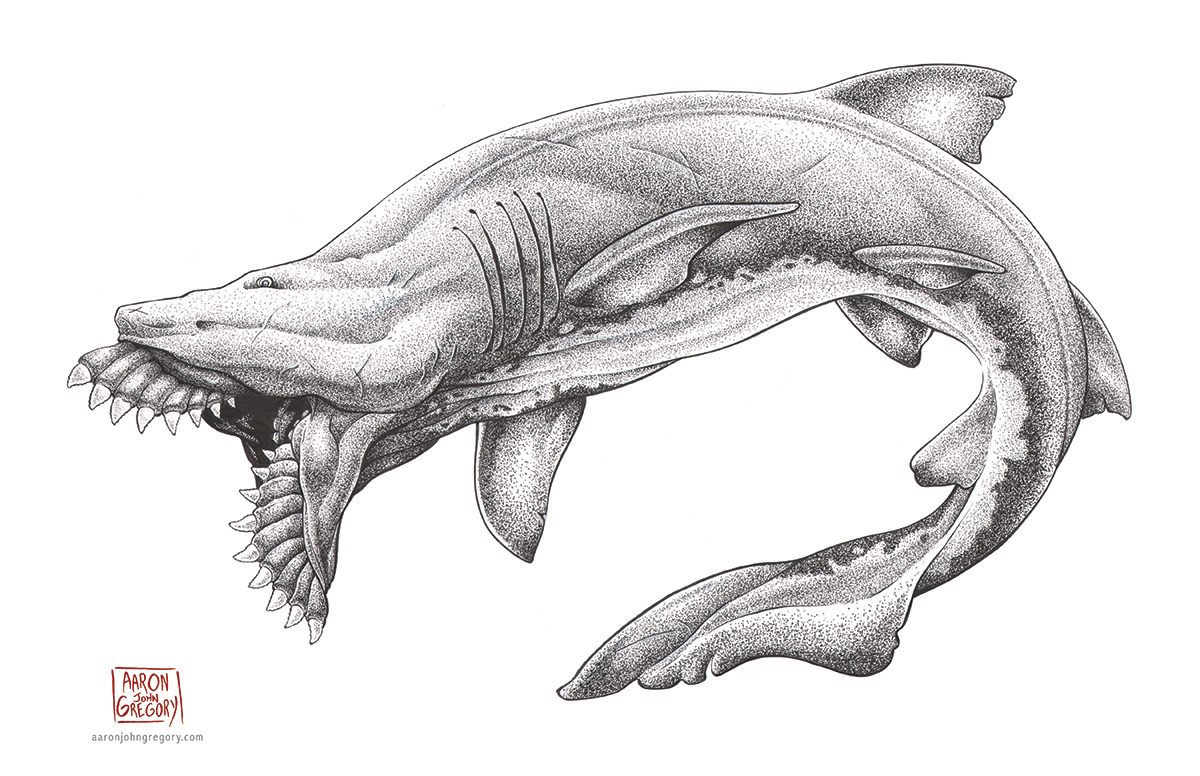

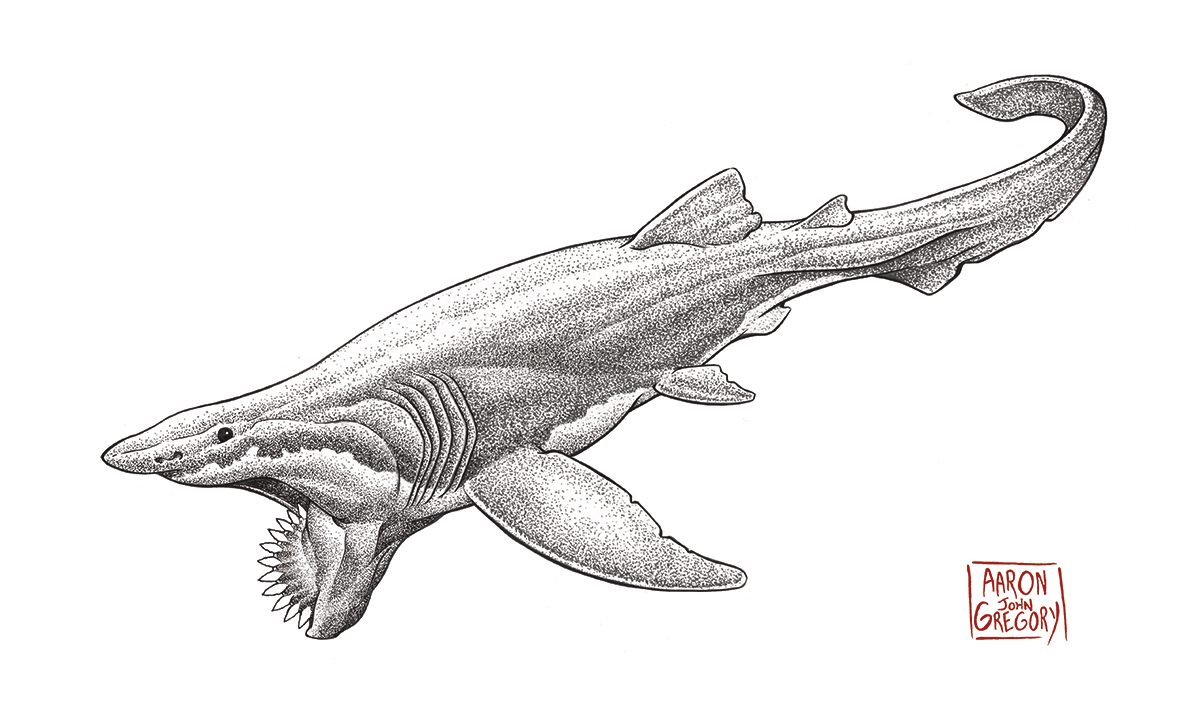

One such artist is Aaron John Gregory, a scuba-diving scientific illustrator. When he’s not in the recording studio laying down bass for his band, SQUALUS—Latin for “shark”*—he’s working on book covers, museum displays, and comic books, like Godzilla: Rage Across Time. But his muse is the prehistoric shark—the more monstrous, the better.

Take Edestus giganteus, a fearsome beast, thought to have been more than 20 feet long. According to Gregory, Edestus may be the “most horrifying shark to have ever lived.” And his illustration of the colossus certainly lives up to the hype; teeth like serrated shears, jaws bulging with veins, a tail built for thrashing.

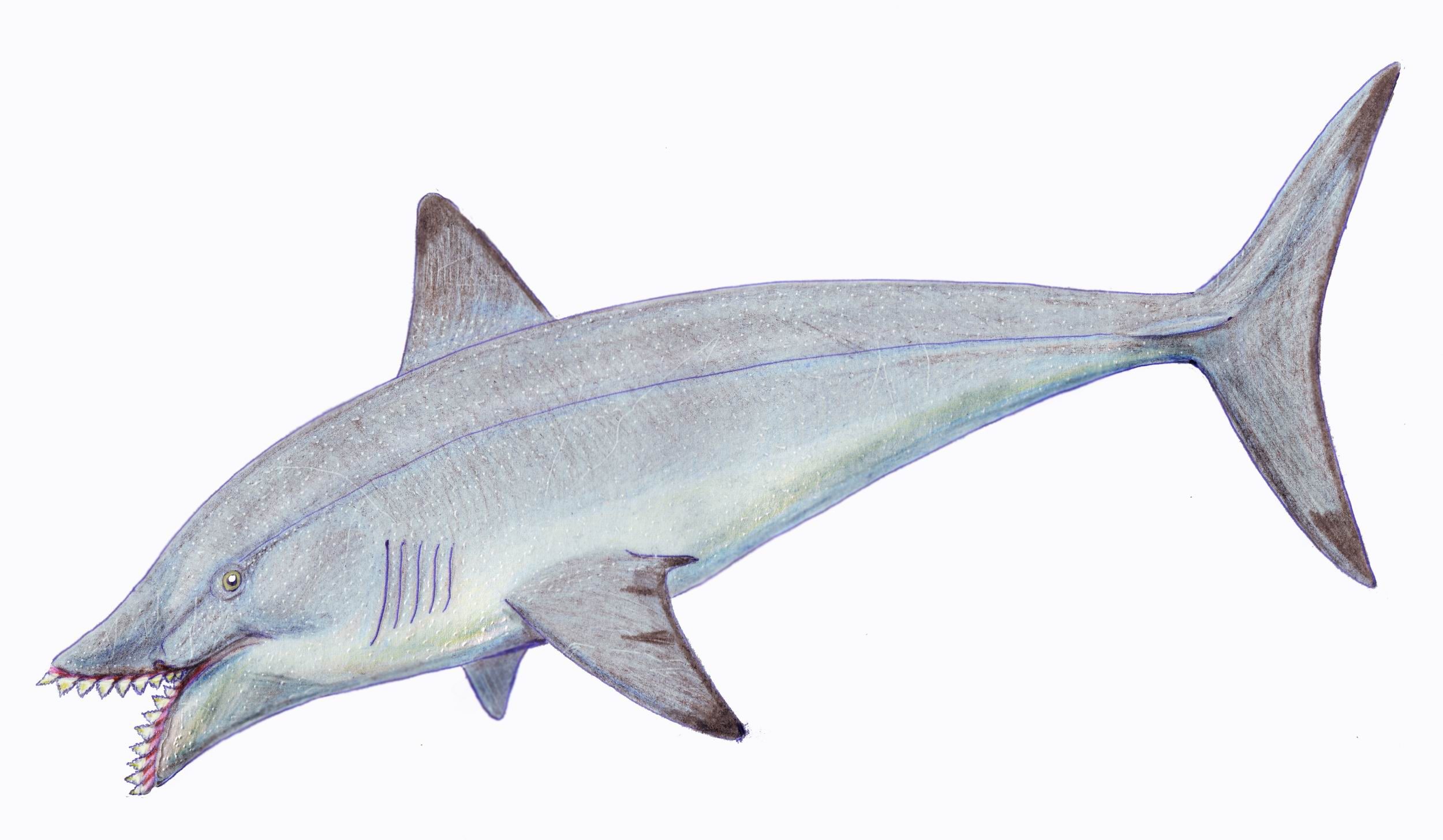

The temptation to take this portrayal as objective truth is strong; it fits the narrative of a hostile, primordial pre-human world. But Gregory is the first to point out that this is an artistic take on Edestus; it shouldn’t be upheld as indisputable fact. Other illustrators’ representations of the ancient shark are markedly different, both in anatomical detail and style. In this sketch by paleo-artist Dmitry Bogdanov, which shows up under the Wikipedia entry for Edestus, the creature is hardly differentiated from today’s sharks.

Because nobody has ever seen an intact Edestus, scientific illustrators are required to play detective, using what evidence remains to flesh out a complete picture. As with all prehistoric creatures, the fossil record is our main resource in determining how these creatures looked and lived.

For bony animals, like the Tyrannosaurus rex, fossilized remains give archaeologists pretty reliable blueprints. When you find an entire skeleton, not much is left to the imagination. Sharks, on the other hand, are soft-bodied animals. They are made almost entirely of cartilage, which rarely fossilizes. So the artist takes on a bigger role, drawing upon knowledge about other sharks, anatomical structures, and limited fossil evidence to reverse-engineer the creature in question.

In Edestus’s case, the only fossilized remains that have been discovered are her jaws. This means that the preponderance of Gregory’s illustration is based on educated guesswork. The gaping, carnivorous maw? Empirical grounding, the basis for everything we know about Edestus. The rippling, bulging masseters? Probably required to operate such hefty teeth. The curved body? A nod to sharks’ cartilage vertebrae; at a certain length, Gregory postulates, a shark’s soft body can’t support a perfectly straight spine (or, perhaps, this particular shark just has a bad case of scoliosis).Some of these decisions are also informed by Gregory’s style. It’s no accident that he captures Edestus in attack mode, seemingly ready to devour its prey whole. Gregory aims to both inform and inspire with his illustrations; he wants you to be excited about massive prehistoric sharks, so he infuses his work with action.

There’s a tension here, between scientific accuracy and artistic expression. Finding the right place on this spectrum is a huge responsibility for illustrators; people often experience scientific discovery through their work, whether in magazines, books, or on television. Space art and photography have been key in galvanizing (waning) public support for NASA missions. A six year old doesn’t want to be a paleontologist because she has a passion for dusting old bones. According to Gregory, “It’s because dinosaurs look awesome.”

Of course, artists can’t go around adding fangs, wings, and aliens to their illustrations to make the science a bit sexier. At the end of the day, they are educators, and play a huge part in shaping the public image of natural phenomena. Just as a bad metaphor or an irresponsible study can engender distrust in the science community, a sensationalized drawing or a dishonest rendering can spread misinformation and encourage science denial.

In 2013, for example, the Discovery Channel aired a Shark Week “documentary” about the possible survival of the Megalodon shark, a prehistoric behemoth that has been extinct for millions of years. Through fictionalized interviews with “scientists” (actors), and “dramatized events” (plot devices), Discovery Channel floated the conspiracy that Megalodon is still alive, now preying on fishing boats instead of ancient whales. Only at the end of the segment were viewers informed that the program wasn’t pure fact, and by then it was too late. The damage was already done. To this day, Gregory said, people will swear to him that the Megalodon is still out there. After all, they saw it in a science documentary.

The Megalodon debacle may seem like a benign example, but it demonstrates the danger of undermining hard science in service of entertainment. The images we have of things too old to have witnessed, too small to be perceived, too large to comprehend are foundational in our conception of the world. We owe many of these pictures to scientific illustrators; at some deep level, they affect how we see things. Are sloths cute or hideous? Depends on whether you’ve seen them napping in trees or bathing in feces. It’s a matter of perspective. To some extent, so is scientific illustration—something between science and art, one person’s understanding that can both illuminate and obfuscate truth.

*Update: We originally said that Gregory’s band is named Giant Squid. That’s the name of his old band.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook