A Chain of Seahorse Hotels Is Coming Soon to Sydney Harbour

“If you build it, they will come.”

Around five years ago, David Harasti had a big idea: to build a hotel. In fact, he wanted to build a whole chain of them around Sydney Harbour. The startup cost would be small, as the hotels were basically boxes made of chicken wire. He knew the demand would be there. After all, Australia’s endangered White’s seahorses—small curvy things that come in bright yellow as well as muddier shades—had lost almost all of their former habitat after a series of devastating storms between 2010 and 2013. Harasti built the first seahorse hotel prototype in 2018, and it was immediately occupied. “Everyone loved the seahorse hotels,” he says. “It was a real, ‘If you build it, they will come’ situation.”

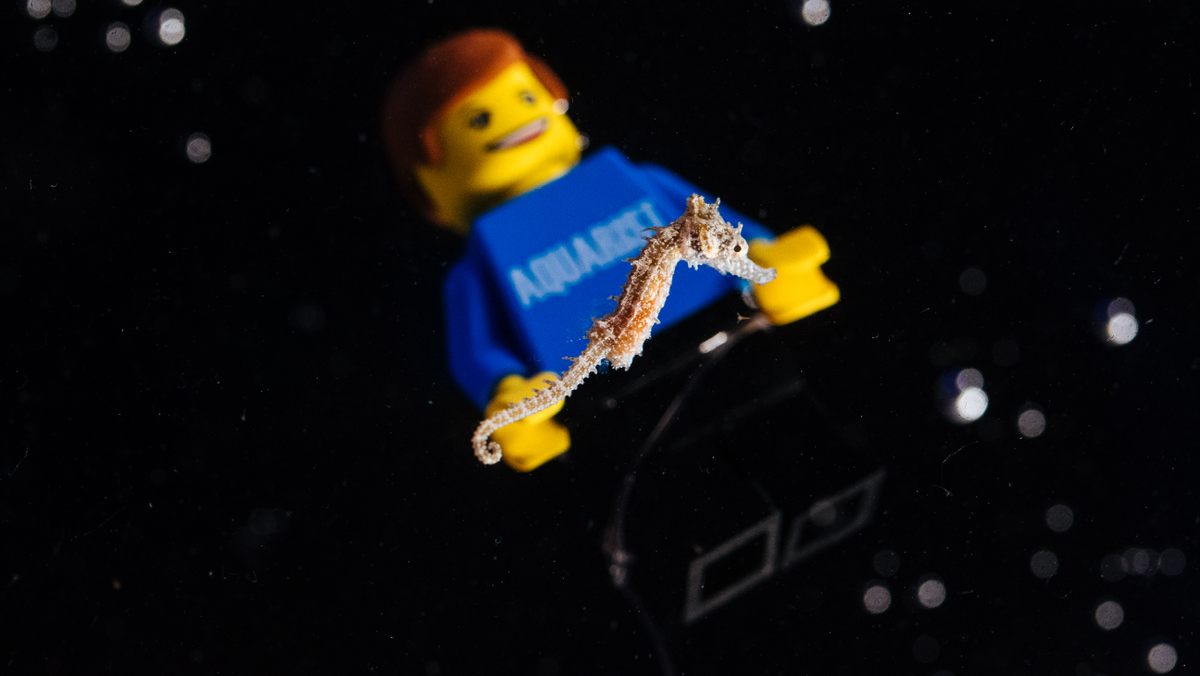

Early next year, Harasti’s hotel chain will see its first large-scale expansion as a part of a new conservation program. Experts at the SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium are currently breeding the fish and raising the fry. Once they’re big enough, the babies will be tagged and released around new seahorse hotels where they will, fingers crossed, thrive, rent-free, for years. If it works, Harasti says, seahorse hotels could be a common site in reefs across the world. “If we lose our habitats, we lose our seahorses,” he says.

Harasti came up with the idea while diving around Sydney. He often spied small congregations of seahorses on discarded lobster traps or shark nets (meant to keep sharks out, not catch them). “They’ve become a spectacle to divers,” says Robbie McCracken, a biologist at SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium. “They’re a pretty crowd-pleasing animal.” Harasti soon realized the fish were attracted to these latticed structures, which offer many gripholds for their signature coiling tails. In accordance with the age-old scientific rule, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” Harasti modeled the first prototype after a lobster trap. It resembled a cage, approximately three feet by three feet, with a metal bar frame and chicken-wire walls .

After installing the initial batch of 18 hotels in the first months of 2018, Harasti returned six months later to find that seahorses had already moved in. By the end of the year, 65 White’s seahorses had colonized the hotels, which also attracted octopuses, schools of fish, wobbegong sharks, neighborly algae, corals, and sponges. In this pilot stage of the study, Harasti experimented with three different prototypes. “The best design for the hotels is completely enclosing them, otherwise predators come in and out,” he says. Harasti has a forthcoming paper that details the specific advantages and disadvantages of each design. (Wire roofs, in particular, seem to be essential for keeping predators at bay.)

Though the structures don’t look like much, Harasti calls them hotels—rather than, say, apartments—because they are meant to be temporary. “I had only planned on them staying for a while, but these seahorses have actually become permanent residents,” he says.

The entire hotel is really just scaffolding to invite the growth of coral—which attracts plankton, copepods, amphipods, and other little animals that seahorses prey on—on which the seahorses can remain after the aluminum breaks down. “The success of the hotels depends on what accumulates on them,” Harasti says.

While Harasti builds the new batch of hotels for the 2020 release, McCracken keeps a watchful eye over their future residents at the SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium. For the past six months, he’s been breeding six mated pairs, brought in from the wild. They all live in one tank, which McCracken designed to replicate their “natural” environment—complete with some squares of shark net, algae, and a continual supply of live invertebrates. The tank has lights timed to fade in and out with the sun, which provides the environmental cues wild seahorses rely on for breeding, he says.

Since early October 2019, right before their breeding season, and the fish have had hundreds of babies. “I was nervous to see how they would assimilate in their new aquarium, and if they would get pregnant,” he says. “They’ve definitely gotten pregnant again and again and again.” When the babies are born, they’re approximately the size of grains of rice. Even though each pair has had several litters, McCracken still loves watching the fathers give birth through a series of violent contractions that push out teensy fry like a sprinkler. “Each time it’s different, anywhere from five minutes to 45 minutes,” he says.

The seahorses have been successfully bred in captivity before, but not on this scale. McCracken plans to keep watch over the babies until April or May 2020, when they ought to be large enough to survive in the wild without being eaten immediately. “When they pop out, little baby seahorses are small and crunchy, little underwater Maltesers,” Harasti says, comparing the animals to the British chocolate-covered malted milk treats originally marketed to women.

Before the young seahorses are released, McCracken will mark each with a code of three permanent neon spots—plastic elastomer injected just below the skin. They will allow Harasti and other divers to track who survives and sticks around in the new digs.

Harasti’s hotels are strangely cosmopolitan chain. He’s taking tips from other seahorse hotels around the world—variations of his initial prototype that conservationists have fashioned up. “There’s some scientists in Greece who use heavy duty mesh, which worked well,” he says. His latest hotel blueprint uses heavy-duty steel frames, which will corrode less quickly than the original aluminum ones.

Luckily for the scientists who study them, seahorses tend to settle in wherever they wrap their tails, Harasti says. The creatures are also rather long-lived, so Harasti has named a few of his favorites that he revisits whenever he can. A few years ago, there was the dark gray Grandpa. “He was quite old,” he says. And there was also Goldie, a real favorite until Harasti watched her get eaten by an octopus. “I ended up fighting with the octopus to get her body,” he says. He was successful and sent the body to the California Academy of Sciences for a genetic test. Goldie’s remains still reside there.

Now Harasti’s favorite is Dawn, a brilliantly yellow seahorse he first encountered five years ago. “She’s a local celebrity,” he says. Four years ago, Dawn got a boyfriend, a dark gray seahorse that Harasti named Dusk. They’re still together. “They fell in love,” he says, marveling at the two’s faithful commitment to each other, which is typical of the monogamous species but no less remarkable for it. Come to the seahorse love hotel for a night, stay for life.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook