Sold: Sylvia Plath’s Rolling Pin and Recipes

Browned and splattered, a set of recipe cards owned by the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet raised a lot of dough.

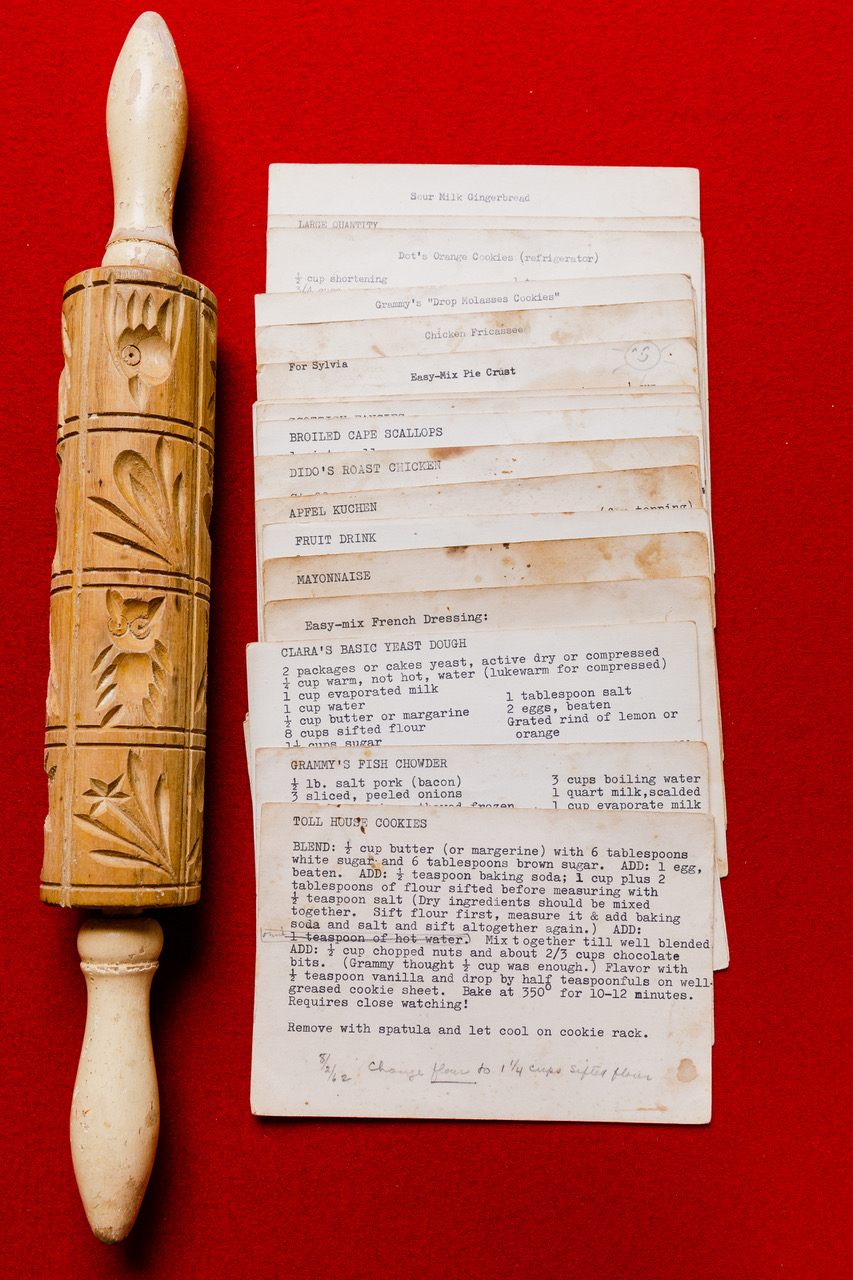

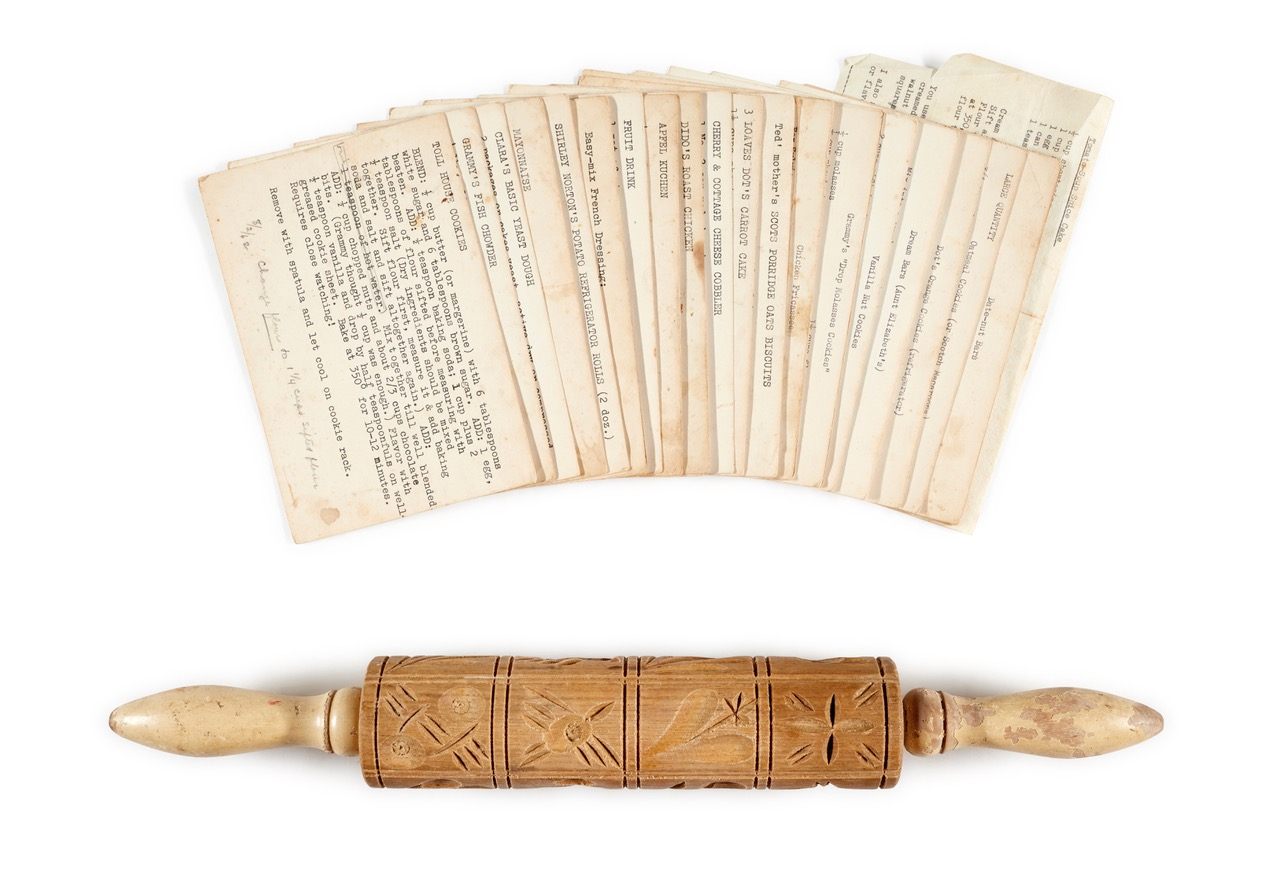

Readers of Sylvia Plath’s diaries and letters will find her whipping up homemade mayonnaise, baking Toll House-style chocolate chip cookies, searing steak, and stewing rabbit. Rarely, though, did the famed poet and writer share her recipes. But this week, 33 of Plath’s typed and hand-annotated recipe cards surfaced at a London auction, sold together with her embossed wooden rolling pin. Plath fans pounced, bidding them up to $27,500.

If the well-thumbed cards are any indication, Plath’s staples included delicacies such as chicken fricassee, cherry & cottage-cheese cobbler, and broiled Cape scallops. They also include family favorites, such as “Ted’s mother’s Scots porridge oats biscuits” and her own mother’s apple crisp. In April 1958, she records in her journal that she is rereading Moby Dick and fixing a “huge fish soup” with “chunks of soaked fish & potatoes,” served with “buttery crackers foundering in it.” Is it one and the same as her recipe for “Grammy’s Fish Chowder”?

The recipe cards were among 55 items recently consigned to auction by Frieda Hughes, the daughter of Plath and fellow poet Ted Hughes, who had already divested many of her parents’ books, photos, and artifacts at two previous sales. Notably, in 2018, Plath’s prized copy of the Joy of Cooking—“It’s the one book I really miss!” she wrote to her mother in 1956—bearing her ink stars and notes, sold for about $6,000.

“She was a fantastic baker and a fanatical cook … cooking for my father was one of her joys,” commented Hughes in an auction house press release. The pieces offered in the recent sale, she added, show “the happiest and the most dynamic part of my parents’ relationship, when they were working at their best together and still very passionately in love and supportive of each other.” Their bliss, however, was short-lived, with her father’s infidelity and her mother’s suicide at the age of 30.

But if it surprises some that the same woman who wrote “I eat men like air” would have contented herself with homemaking duties à la June Cleaver, it shouldn’t, says Peter K. Steinberg, coeditor of The Letters of Sylvia Plath. When Plath attended Harvard Summer School in 1954, she was living on her own for the first time, so she learned to cook and began hosting teas and dinners. “She had no other choice but to learn how to do these things,” Steinberg says, but Plath enjoyed the act of creation, whether it was a meal or a poem.

That drive extended to homemaking, too, after Plath married Hughes. “She was going to do it all, and she did it really well,” Steinberg says. While she embraced the role, she realized she could easily be swept away by it, warning herself in a journal entry from 1957, “You will escape into domesticity & stifle yourself by falling headfirst into a bowl of cookie batter.”

Steinberg, who won Plath’s fishing rod at a 2018 auction, says he obsessed over the recent auction for weeks but was ultimately outbid on the four lots he wanted. When asked why there is such hot market for Plath memorabilia—even her red lacquer chopsticks sold for $3,100—he references one of her quotes, “I love the thinginess of things,” and suggests that this sentiment has been “transferred down” to her die-hard fans. “I don’t think she could have predicted this fetish or desire to have what she had,” he says, “but just the mere fact that these things were saved is meaningful.”

“I’ve always been aware of and appreciated her vivid descriptions of food, mostly because I have always loved literary descriptions of food,” writes Rebecca Brill in an email. Since 2020, Brill has been tweeting daily descriptions of meals Plath cooked or ate. A Twitter follower alerted her to the sale of the recipe cards, and while they were out of her budget, “I harbor fantasies of some wealthy secret admirer buying me that rolling pin.” (The actual buyer of the rolling pin and recipe cards has yet to step forward.)

Beyond their value as relics, the recipes offer a new way to experience Plath. For example, Steinberg and his wife made her tomato-soup spice cake last weekend. The recipe, which the novelist Kate Moses called one of Plath’s “specialties,” had been sent to Plath by her mother and then annotated in pen by Plath in September 1961.

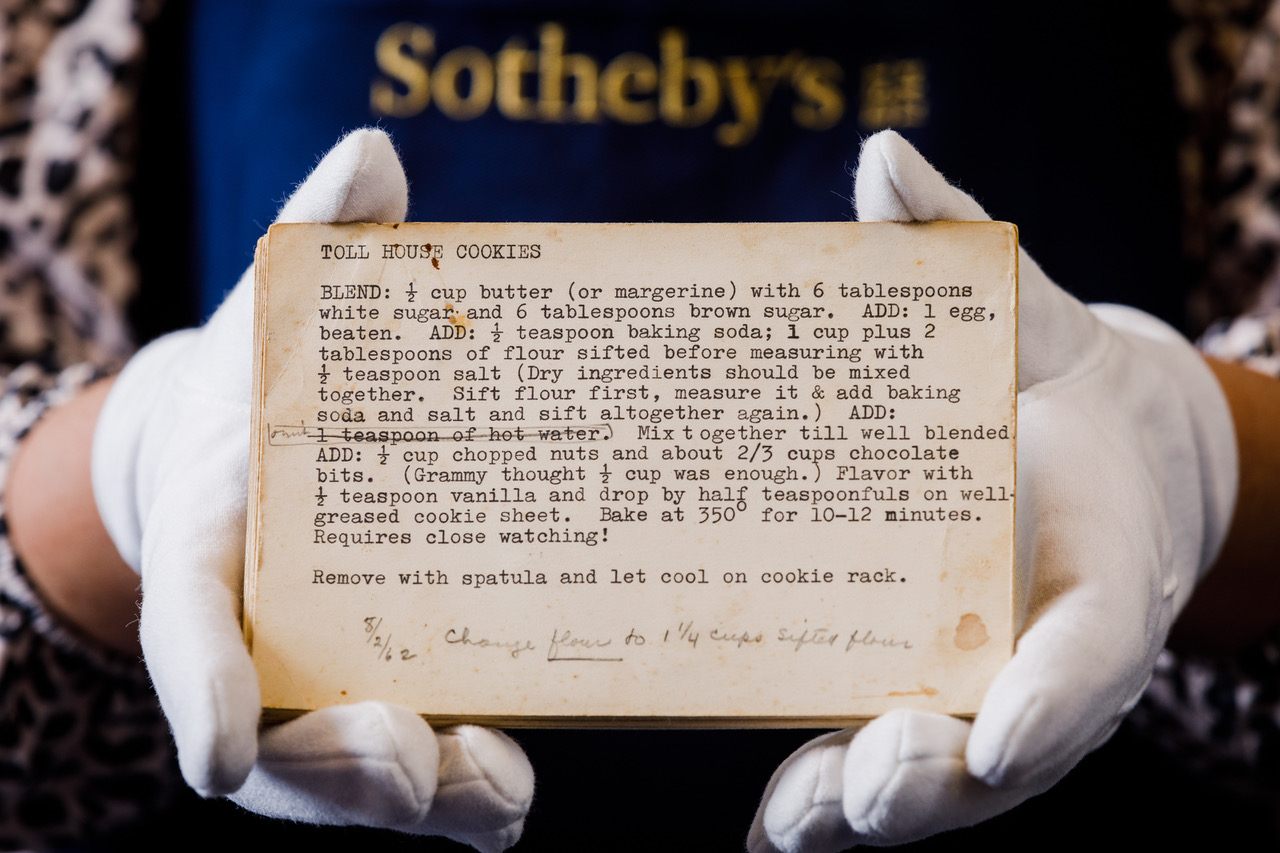

“It was so good,” Steinberg reports. “We didn’t taste any tomato at all.” Unassuming guests might think it a carrot cake, especially when topped with a cream-cheese frosting. Plath fans eager to try one of her recipes can now have a go at her timeworn formula for “Toll House Cookies,” an image of which Sotheby’s published in the run-up to the auction.

Brill hasn’t tried any of the author’s exact recipes yet—though she admits she does sometimes stuff avocados with tuna salad as an homage to a mention of crabmeat-stuffed avocados in Plath’s 1963 novel, The Bell Jar. Her interest in Plath, and more particularly, Plath’s relationship to food, has more to do with “complicating our culture’s image” of her. “When one thinks of Plath’s kitchen, one conjures up that ghastly image of her gas-oven suicide,” she says. “I’m trying to trouble that image by painting Plath’s kitchen as the space of life, joy, and fulfillment it often was for her.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook