This Writer Is Tweeting Everything Sylvia Plath Ever Ate

Busting sexist myths about a famous poet, one tweet at a time.

Like many young, aspiring writers, Rebecca Brill was obsessed with Sylvia Plath’s diaries. Their luminous, sensual, and often dramatic prose charts the ups and downs of Plath’s internal state with a serious attention that young women’s feelings rarely receive. So when the pandemic lockdown began in 2020, Brill, in the grip of a depression brought on by quarantine isolation, turned back to the diaries. “I needed company,” she says.

At the time, Brill was a soon-to-be MFA graduate at the University of Minnesota, and interested in the intimate lives of female writers. Since 2018, she had run an account tweeting out a different daily passage from Susan Sontag’s diaries. In contrast to the writer’s assertive, public-facing personality, Sontag’s diaries depict a woman who struggled with insecurity and loneliness. The aloof writer became someone Brill could relate to.

When Brill revisited Plath’s diaries, she noticed a contrast between the author’s public reputation and her private thoughts, much like what she found with Sontag. The discrepancy centered on one topic. “What really jumped out to me is how much she likes food,” says Brill. “Nearly every journal entry talked about what she’d cooked and eaten.” Upon reading Plath’s letters, she found the same trend.

So on March 23, 2020, Brill sent out her first tweet from Plath’s oeuvre, a description of a meal the poet ate in 1952, when she was still a student at Smith College in Massachusetts.

Swordfish and sour cream broiled. Hollandaise and broccoli. Grape pie and icecream, rich, warm. And port, sharp, sweet, startling gulped with a sudden good sting behind the eyes and a relaxing into easy laughter. Good scalding black coffee. 1952

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) March 24, 2020

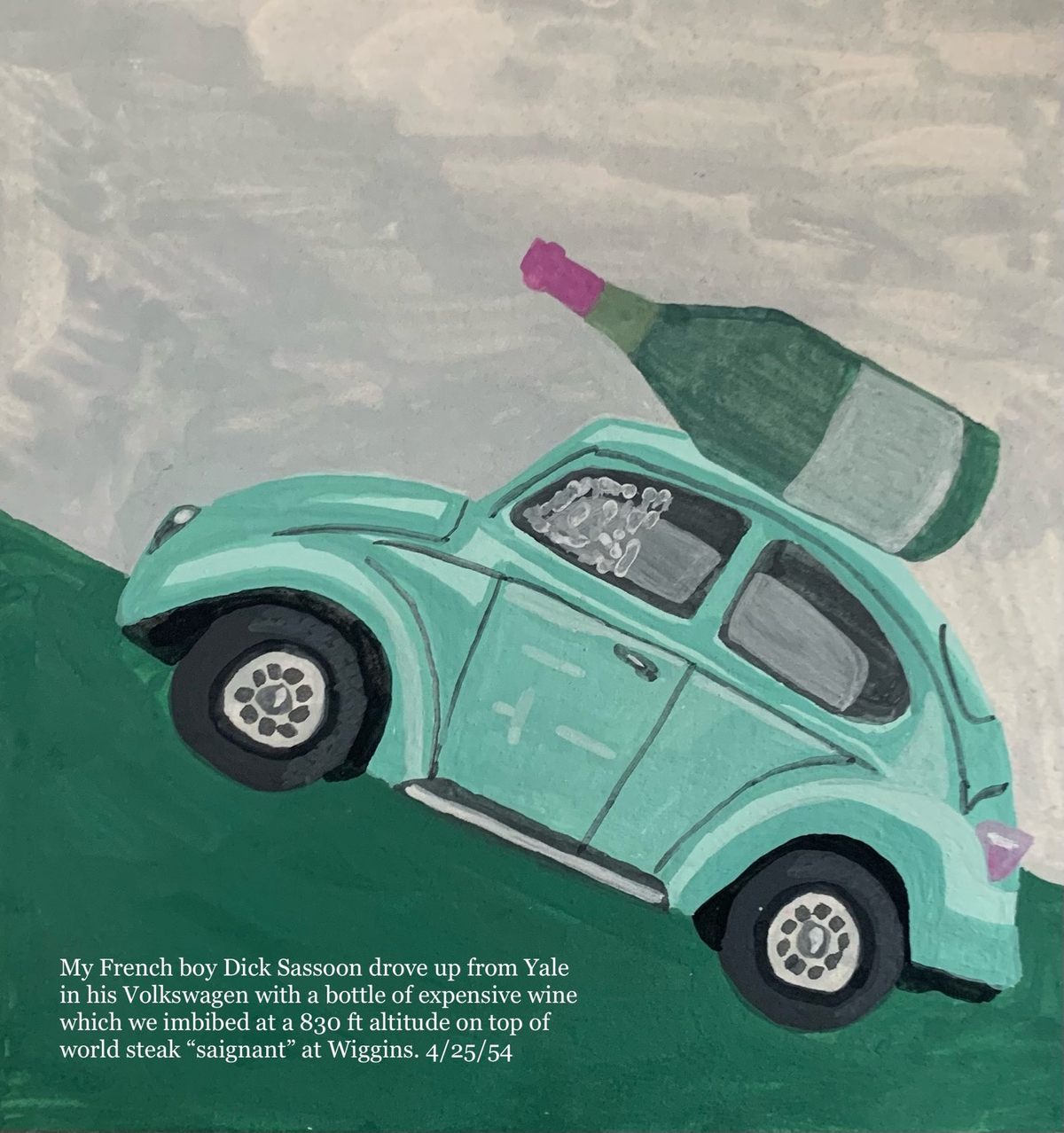

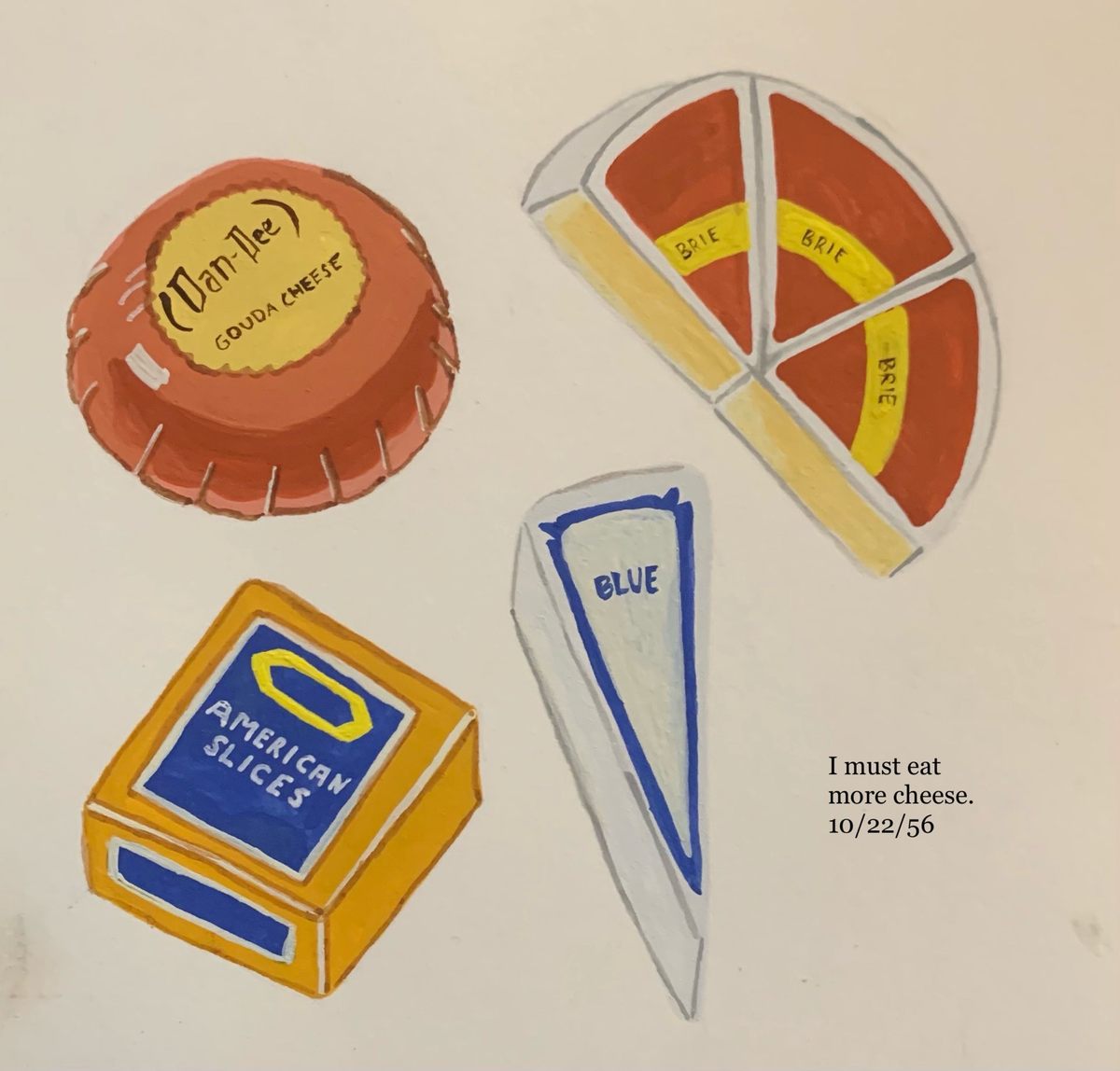

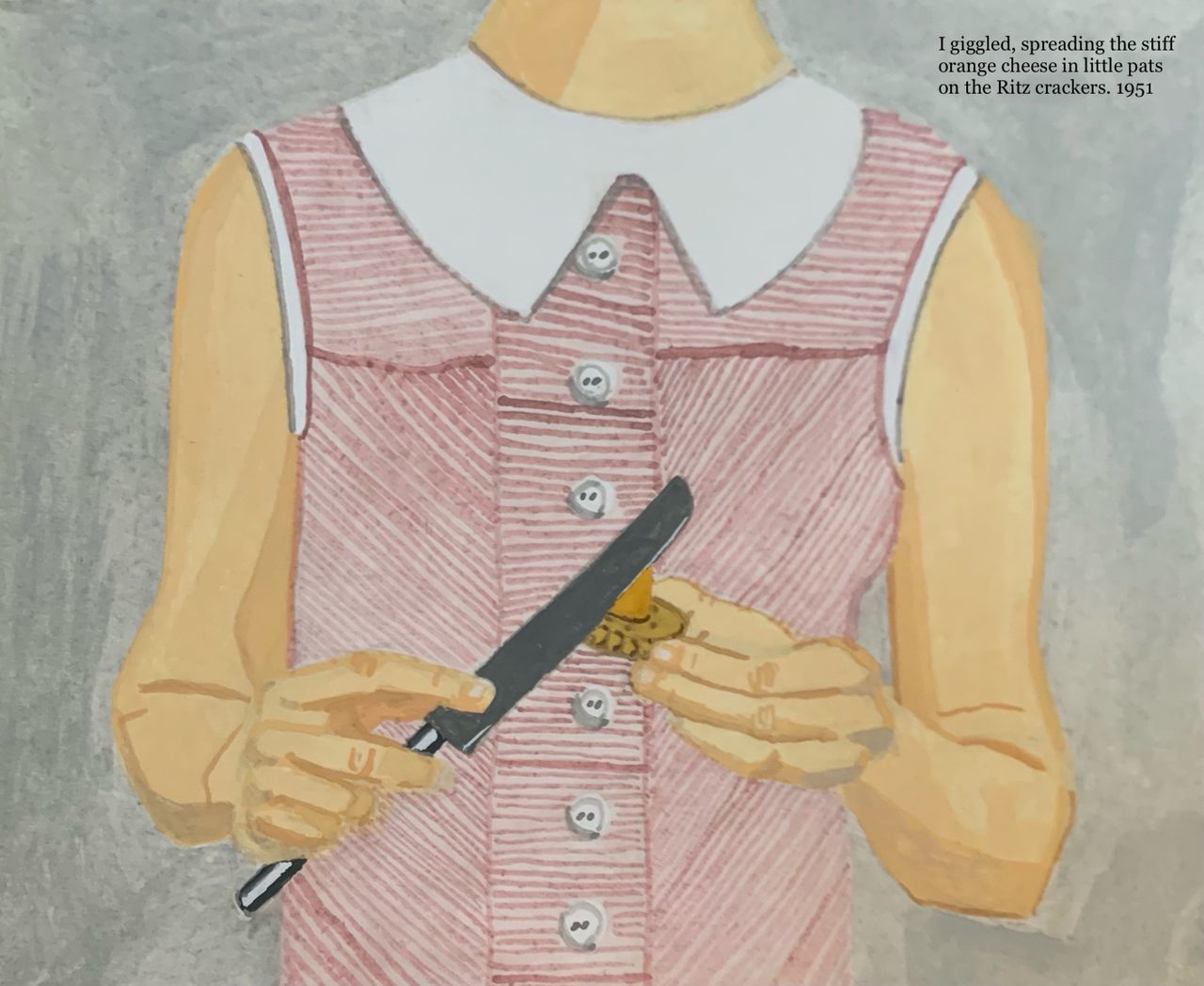

Brill has tweeted out a meal from Plath’s writings once a day ever since. Every Sunday, her collaborator, Lily Gibbs Taylor, illustrates one of the tweets.

Brill doesn’t identify as an avid cook. “I’m by no means a foodie,” she says. But as a writer, she has a gnawing curiosity for intimate details; she’s the kind of person who’s always asking her friends what they eat. In Plath’s case, the focus on food provided a counter-narrative to the popular portrayal of the poet as an alluringly waifish, doomed woman.

“A lot of people don’t know that much about Sylvia Plath, but know the story of her suicide,” says Brill. Plath, who struggled with depression her entire life, committed suicide in 1963, at the age of 30, by inhaling oven gas. According to the popular myth of Plath’s suicide, Brill says, “She felt so trapped by domesticity that she stuck her head in the very trap, the very cage that was entrapping her.” Plath’s marriage was indeed traumatic; she described physical and emotional abuse at the hands of her husband, poet Ted Hughes. Yet many accounts of Plath’s life respond to this hardship by glamorizing Plath as a tragic figure, too lost in poetry for daily realities such as food, and possibly suffering from anorexia.

It’s true, says Brill, that Plath’s journals are full of fear that her socially imposed duties as a wife and mother will drown out her poetic voice. Several of her food descriptions embody this tension, as in this description, when a 19-year-old Plath worries that she’ll have to marry and sacrifice her career.

God, must I lose it in cooking scrambled eggs for a man? 1951

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) February 12, 2021

Yet Plath’s diaries reveal a much more complex relationship to food and domesticity than portrayed in most popular depictions of Plath. As much as Plath resented the patriarchal limitations placed upon her, she also enjoyed the sensuousness of daily life. The diaries include a relationship to food that was often pleasure-filled, abundant, as in this reflection from a London dinner with Hughes, shortly before the birth of her first child.

We had lunch with Ted’s editors & dined sumptuously at a Greek restaurant, blissfully ignoring prices—on chicken liver & salmon roe pate, a Moussaka of cheese, aubergines, rice & chicken, Greek resinated wine, & a heavenly bowl of magnificent fresh fruit & cream for me. 3/3/60

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) March 3, 2021

Some of Plath’s food descriptions are downright sexy.

I drink sherry and wine by myself because I like it and I get the sensuous feeling of indulgence I do when I eat salted nuts or cheese; luxury, bliss, erotic-tinged. 1953

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) September 19, 2020

Other entries showcase Plath’s enjoyment of cooking, including full recipes she noted for herself or in letters to loved ones, such as this one, which she wrote while living in England.

Have you tried this recipe for red cabbage? It’s especially good with pork or sausages. Saute an onion or two, chopped fine, with a few strips of bacon, cubed. 3/17/60 (1/2)

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) March 17, 2021

Add a cut-up red cabbage, shredded, which has been soaked in cold water, 2 tart cooking apples, sliced fine, a handful of raisins or sultanas & a cup of cider or red wine. Cover tightly & simmer for 2 hours, adding more cider or wine when the first is absorbed. 3/17/60 (2/2)

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) March 17, 2021

Some entries do bear the mark of Plath’s depression, but in a more nuanced way than the simplistic “caged-by-domesticity” narrative would imply. “A lot of times the food is mocking Sylvia,” says Brill, including in these descriptions from her time as a Fulbright scholar at Cambridge.

And I drank the last of the bad sherry, and cracked a few nuts, which were all sour and withered to nothing inside, and the material, inert world mocked me. 2/19/56

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) February 19, 2021

Last night’s whiskey with Hamish, glass after glass tossed down, at least five or six, is still strutting latent havoc in my veins, ready to betray me; the caffeine from the coffee this morning tenses fiber too, and I am appalled. 3/10/56

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) March 10, 2021

Some meals Plath recounts are downright strange, a reflection of both the wild culinary world of the 1950s and ’60s, and Plath’s idiosyncratic tastes.

I created an esoteric dinner beginning with jellied consomme in champagne glasses, an elegant compote of sliced peaches, grapes, cherries and apples marinated in sherryandlemon dressing, cheese and crackers, chocolate cake and hot coffee. 8/4/54

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) August 4, 2020

And sometimes, Sylvia Plath’s relationship to food—like all of ours—was simply mundane.

Hot tea, a devilled egg and a face wash 1959

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) January 25, 2021

Plath’s diaries reveal that she had a rich, complex, and passionate relationship to food. So why do myths persist about Plath as a poetic pixie too ethereal for the realities of daily life?

Brill, a literary nonfiction writer herself, says this partly has to do with the patriarchal literary establishment’s desire to fetishize female writers’ aesthetics or sexuality, thus minimizing their intellectual abilities. Plath is often portrayed in pop culture through the lens of what some have called “the cult of the literary sad woman.” The sad woman in question is normally white, conventionally beautiful, and thin.

“What’s really dangerous about that trope, in addition to possibly glamorizing anorexia, is that it makes it seem like the ideas are not coming from their own minds—that they’re just conduits to the muses,” says Brill. The sad, white literary woman’s self-harm is often sexualized, and depicted as the “natural” result of talent too bright for this world. In contrast, a woman of color or larger woman might be stigmatized as shamefully sensuous, and her experience of mental illness as grotesque.

In debunking sexist stereotypes from the perspective of food, Brill’s work follows the example of other feminist writers and historians, including Barbara Ketcham Wheaton and Laura Shapiro, who have shed light on the intertwined histories of cuisines and women’s lives. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s not only a great topic—it’s the topic,” says Shapiro, whose most recent book, What She Ate, retells the biographies of six famous women though their experiences of food. “When you look at food, you see everything.”

This is particularly true for women, who have been disproportionately responsible for domestic labor, yet whose stories remain undertold. “You couldn’t write about food without writing about women, and you certainly couldn’t write about women without writing about food,” says Shapiro.

Despite the centrality of food to women’s narratives, however, mid-1900s feminist historians and journalists often avoided the topic, afraid of reinforcing the idea that women “naturally” belong in the kitchen. “The idea was women in power, women in education, women in politics, women and birth control and abortion. All those big issues,” says Shapiro.

Yet by focusing on food, feminist historians and writers often uncover a more nuanced view of historical women’s daily experiences. They present women as multifaceted people, rather than either public trailblazers or prim domestics. “When you cook and shop and think about food, it’s not that you’re doing it in poetic meter, but you are the same person. It’s not that we’re compartmentalized,” Shapiro says. “Sylvia Plath is a prime example.”

Indeed, says Brill, the journals provide evidence that Plath’s creative and domestic lives were not constantly at odds. Instead, the line between her domestic and creative work was much more fluid. Many of Plath’s journal passages about food read like experiments in descriptive language. Several have the sensuous heft of her best poetry.

Spooned up watery red soup, talked of Cambridge England, ghost-haunted. Then the uncuttable tough florid-pink tongue, the watery orange turnip, mashed potato, slippery dressinged lettuce, lucent & fresh as a drink of water. Apple pie & cheese & coffee. 1/21/58

— Sylvia Plath’s Food Diary (@whatsylviaate) January 21, 2021

Brill hopes that this historical reimagining offers, tweet by tweet, a more nuanced and joyful portrait of a complex woman. “I think it’s important to break down that stereotype and also show that Sylvia Plath had a lot of fun,” says Brill. Over the past year of lockdown, Plath has added zest to Brill’s life, too, keeping her creatively nourished through a lonely quarantine. “It’s like I’m having dinner with Sylvia Plath.”

Sylvia Plath’s Heavenly Sponge Cake

This recipe, from a May 25, 1959 letter, is in Plath’s own words.

Here is a heavenly sponge cake recipe which you should make in a high cake pan with a funnel in the center so the cake has a hole in the middle.

6 eggs (separate)

1½ cups sugar (sifted)

1⅓ cups cake flour

1½ teaspoons baking powder

¼ teaspoon salt

6 tablespoons water

½ teaspoon lemon extract

1 teaspoon vanilla

Directions for sponge cake: Beat yolks till lemon colored. Add sugar gradually. Add water & flavoring. Add flour gradually, beating. Beat egg whites to froth; add baking powder and salt to frothy egg whites. Beat until very stiff. Fold gently, but thoroly into egg yolk mixture. Sprinkle granulated sugar lightly over top of cake before putting it in the oven. Bake for one hour at 325. Do not remove cake from pan till cake is cold.

If you or a loved one are experiencing thoughts of suicide, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can help. You can chat online or call 1-800-273-8255 to access 24/7 support.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook