To Protect Pennsylvania’s Hellbender, Teenagers Made It the State Amphibian

The Eastern hellbender looks like a long, slimy potato and is sometimes called a snot otter.

North America’s largest amphibian, the Eastern hellbender, looks like a long, slimy potato and goes by many names: snot otter, lasagna lizard, mud puppy. “They’re not as squishy as you might think,” says Anne Puchalsky, a freshman at Pennsylvania State University who has become an unlikely champion of the species. Hellbenders are a kind of salamander, but to Puchalsky, they stand out from their aquatic brethren. “They’re breathtaking,” she says.

Puchalsky and her friends are largely responsible for the Eastern hellbender’s newest moniker: official state amphibian of Pennsylvania. It all started, strangely enough, with a plastic model of a hellbender. His name was Harry.

When Puchalsky was still in high school, she and several classmates signed up for a science program called the Student Leadership Council, which is hosted by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “We’re an environmental organization, so we have a lot of random artifacts floating around: canoe paddles, anchors, hellbender models,” says Emily Thorpe, who coordinates the program at the foundation’s Pennsylvania office. When the students saw the model, Thorpe says, “they started asking questions about hellbenders.”

To find answers, the students turned to the Clean Water Institute at Lycoming College in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. There, Dr. Peter Petokas and his colleagues have spent two decades researching the elusive hellbender.

Hellbenders are introverts. They spend most of their lives in cool mountain streams under “rocks the size of cars,” Petokas says. Until recently, “no one seemed to know about the hellbender in Pennsylvania. No one knew where they were or how they were doing.”

As Petokas discovered, the hellbender was not doing well. Like all amphibians, “hellbenders breathe through their skin,” Petokas says. “Any changes in the water will be reflected in the health of the species itself.” He and his team found that pollution, warming water, and impounded streams were causing a significant decline in their population.

After a decade of field research that yielded some concerning conclusions, scientists at the Institute switched gears from discovery science to applied conservation. They began raising hellbenders from eggs, microchipping them, and releasing them into the wild. This work required them to construct artificial shelters for the amphibians. In other words, they had to move around massive slabs of rock. “These shelters weigh a lot,” Petokas says. “It’s hard work, it’s wet work. And we needed a lot of help.”

That’s when Thorpe and her students happened to call. They volunteered to help build shelters and learn about the hellbender from the experts. Students spent time in the field building habitats, learning all the while about the challenges that the hellbender and other aquatic animals face today. They began to brainstorm how they might call attention to the issue of worsening water quality in Pennsylvania.

One idea they kept coming back to was a campaign to designate the hellbender as the official state amphibian. About half of US states have one, and Pennsylvania did not. “It seemed bipartisan,” says Emma Stone, outgoing president of the Council and now a freshman at Mansfield University. “We didn’t have a state amphibian, and the Eastern hellbender is not another state’s amphibian. We thought, ‘Who’s going to say no?’”

The campaign kicked off at a Panera in the suburbs of Harrisburg. Over sandwiches, and with samples of similar legislation as their guide, six high school students drafted a bill that touted the hellbender as “a positive symbol for water quality in the state.” With a convincing bill in hand, the students began seeking a sponsor in the Pennsylvania State Senate, someone who would introduce it for a vote. They found that champion in Senator Gene Yaw, a Republican who chairs the state’s Chesapeake Bay Commission.

Of course, he wasn’t going to sign on without asking some tough questions of his own. “I told them, let’s be honest about it, they were looking for some sucker to introduce a piece of legislation in the middle of a budget crisis, and we’re going to talk about a salamander,” Yaw later said in a news conference.

Luckily the students had done their homework—literally. “He challenged us to see how much we knew,” recalls Stone, “and how much we cared.” The students made an impression. “These are a bunch of bright kids,” Yaw said when he introduced the bill to his colleagues. “They’ve got some good ideas. They studied this.”

It took six months for the bill to pass the Senate and move to the House. But that’s where the gears of civic progress ground to a halt. Representative David Reed, also a Republican, quickly introduced a bill that aimed to make an entirely different creature the official state amphibian: the Wehrle’s salamander, a small, plum-colored amphibian discovered in 1911 by a naturalist from Indiana, Pennsylvania.

“It was offensive,” says Hanna Ryon, a senior at Biglerville High School outside of Gettysburg. “We took it personally.” For more than a year, the now-contested bill languished in a House committee. Undeterred, the students launched a public relations campaign to drum up support for the hellbender. “We found out quickly that people love free stuff,” says Ryon.

There were Hellbender Defender t-shirts, temporary tattoos and sugar cookies. Students kept knocking on doors and calling their representatives. They continued wading into Pennsylvania streams, planting riparian buffers and building hellbender shelters. During a meet-and-greet at the Pittsburgh Zoo, they even got to meet the amphibian of the hour. “I know they’re really ugly,” Ryon says of the first time she laid eyes on a hellbender. “But I got choked up.”

Despite their persistence, when the 2018 legislative season ended, the hellbender bill died in committee. At the next Council meeting, the students took stock. Thorpe remembers asking them, “Do you want to keep doing this?” The students were unanimous. “They didn’t think long about it. They wanted to move forward.”

The 2019 session opened without Representative Reed—he had given up his seat to run for US Congress—or any mention of the Wehrle’s salamander. This time around, the bill flew through the Senate, and a few months later the House took up the vote. In a famously partisan state, it passed with overwhelming support from both parties, 191-6.

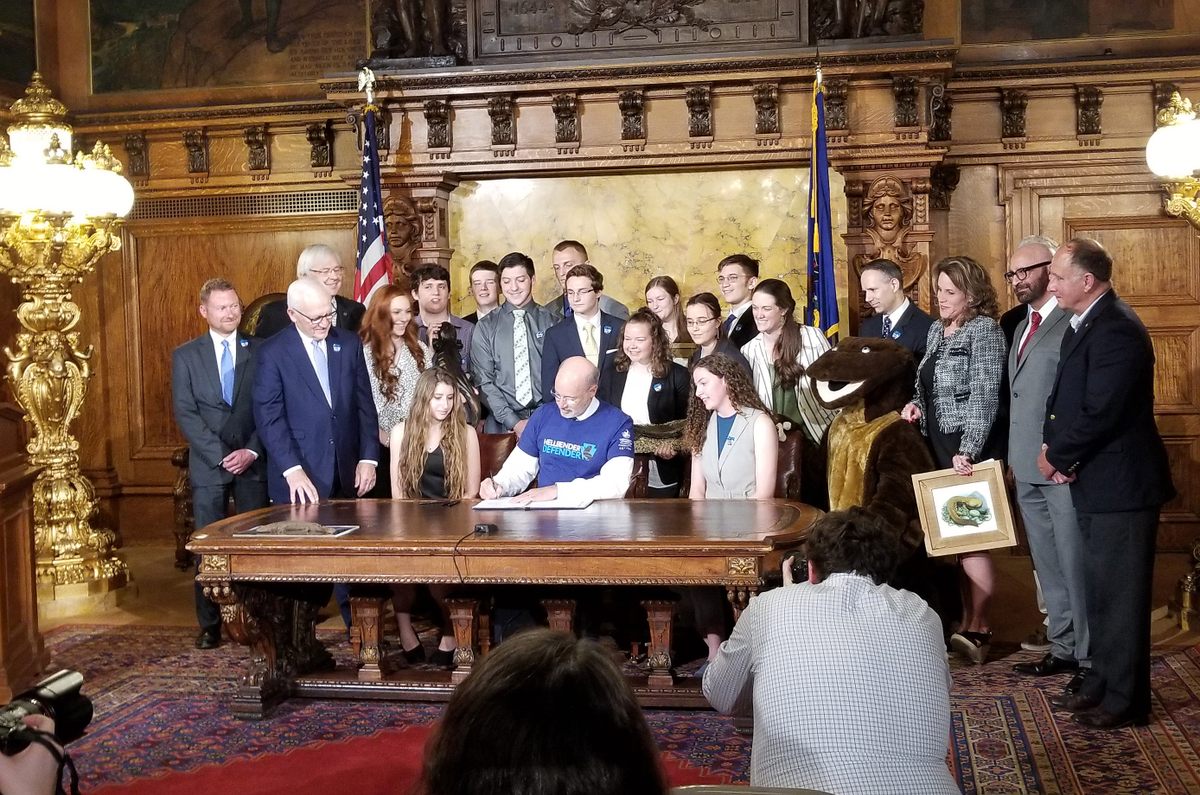

On April 23, Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, wore a blue Hellbender Defender t-shirt as he signed the bill—the same one that high school students wrote in a suburban Panera—making the Eastern hellbender Pennsylvania’s official state amphibian. Emma Stone sat beside him. “It was so surreal,” she says. “We were high schoolers.”

While the designation was a major victory, Thorpe is quick to point out that it brings with it no special status or state protections. The fight to help the Eastern hellbender must continue. “We can do better, and we can do more,” she says.

The Council already has a new mission. They’re promoting the Keystone 10 Million, an initiative that aims to plant 10 million trees in the state by 2025. One of its goals is to improve water quality for threatened species like the hellbender. “People say, ‘You’re too young to make a difference,’” says Ryon. “But now we know that’s not true.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook