The ‘Balloon Maps’ That Aided Exploration, War, And Tourism

See the world from the basket of a hot air balloon.

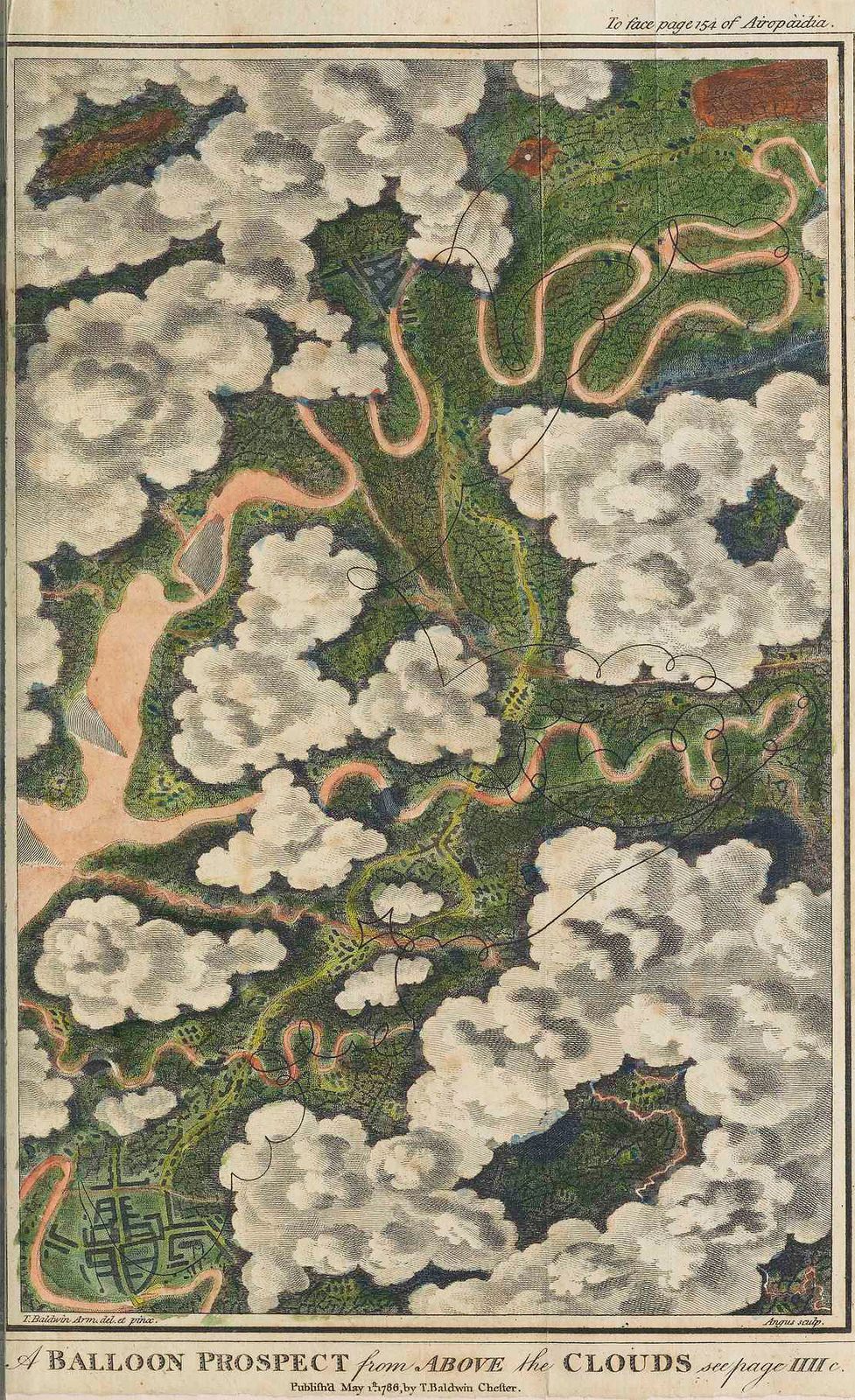

In 1785, a man named Thomas Baldwin lived out an 18th-century dream: he floated over Chester, England in a hot air balloon. When he came back down, he puzzled over how to share this rare experience—the “white floor of Clouds,” the “exquisite and ever-varying Miniature” of the buildings, and the look of the rivers, “infinitely more serpentine” than ordinary maps would have you believe.

Along with pages of rhapsodic description, he settled on three illustrated plates, for which he had specific viewing instructions: put it on a table, roll up a piece of paper into a little telescope, and look through it while moving it slowly over the drawing, so you can have your very own balloon experience.

In an age of transatlantic flights and Google Earth, Baldwin’s suggestions seem a bit quaint. But in his time, when almost everyone was stuck on the ground, Baldwin’s attempts to pin down an accurate sky-view were heroic. Over the following century, entrepreneurs, military spies, and tourist boards alike would follow his lead, transforming some of the world’s most vital views into lovely, quirky “balloon maps.”

“Ballooning had a profound effect on the epistemological mode of being in the world and viewing landscape,” writes historian Lily Ford, who examines Baldwin’s work in the Public Domain Review. According to Ford, Baldwin was ahead of his time—no one would draw a balloon map for decades after his initial attempts. But in the late 1700s, as balloons began rising over France and Britain, stories of high-flying pursuits inspired ordinary civilians, who began seeking out different modes of seeing. The invention of the panorama in 1792 was accompanied by a new type of entertainment, Ford writes: the view-from-above.

Entrepreneurs would install a 360-degree view of a city or a battle in, say, a large barn, and patrons would pay to climb up a tower and look down at it. The effect was so realistic that people would sometimes get sick, writes Ford. Meanwhile, growing leagues of balloonists finally had a good metaphor for their own experiences—the view from the basket brought to mind nothing so much as a panorama, they wrote, over and over.

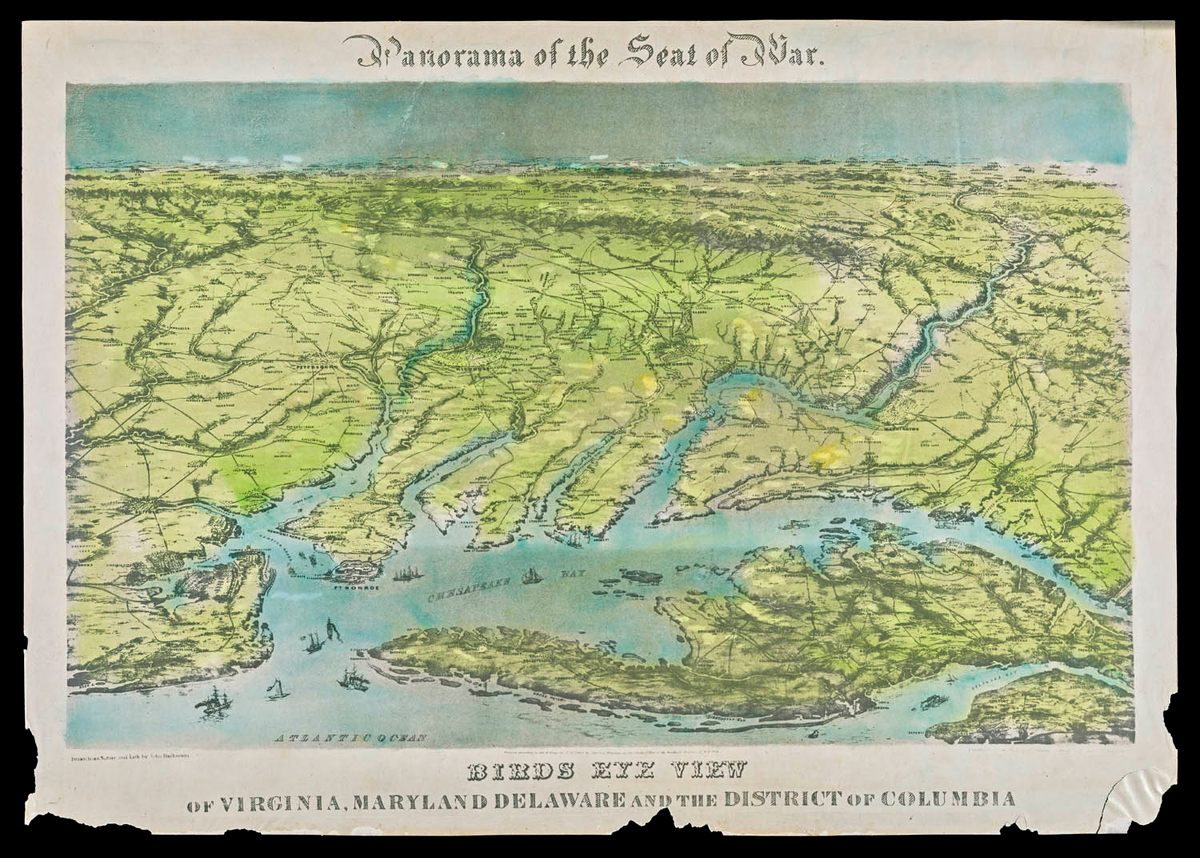

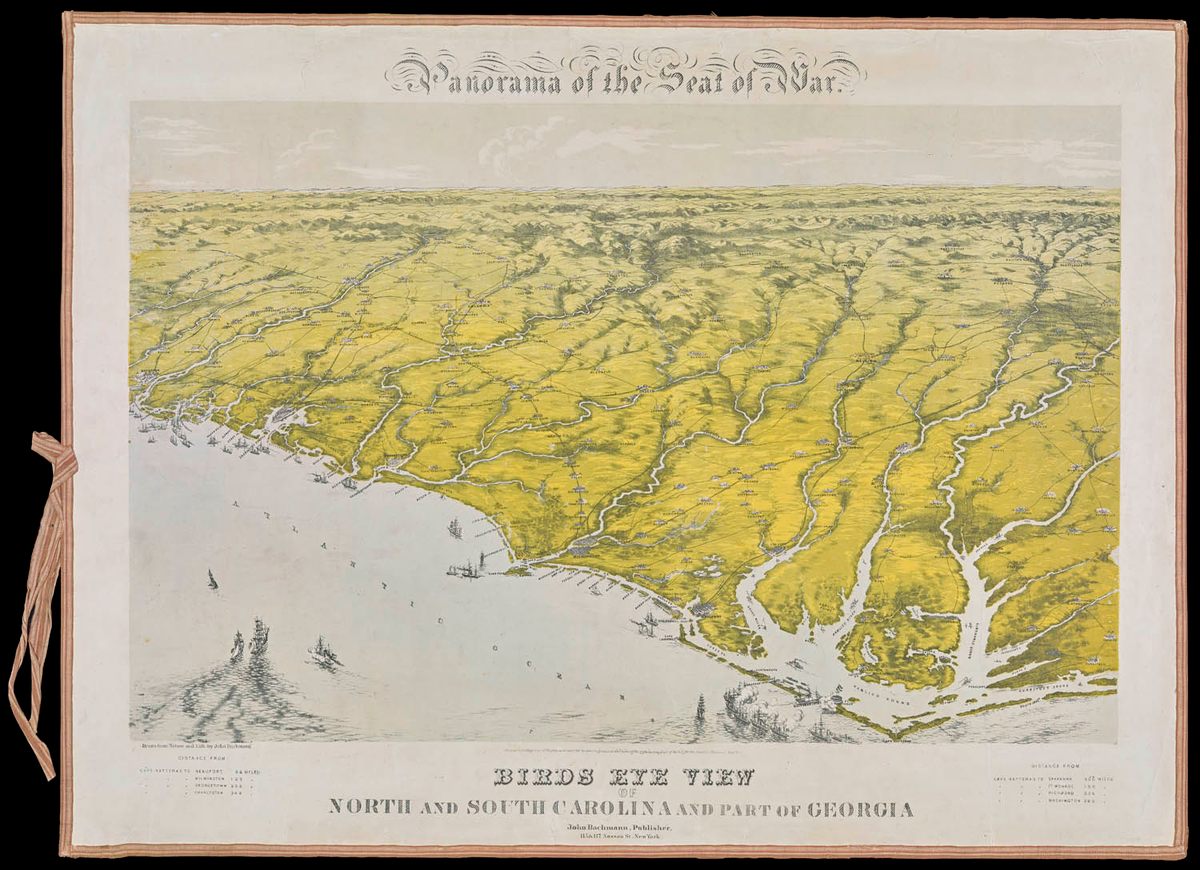

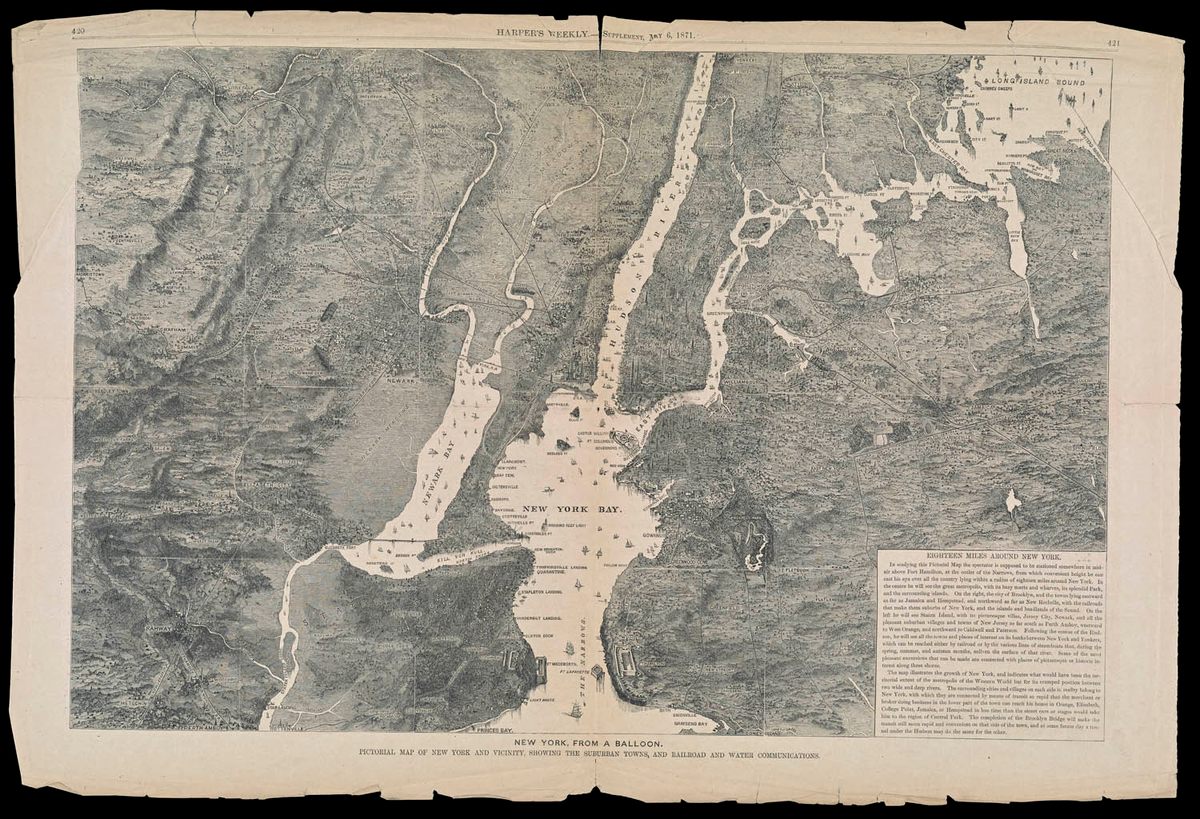

American balloonists got to put these analogies to the test during the Civil War, when the Union Army used balloons for scouting and surveillance. Not much mapmaking went on from the balloons themselves—it was pretty shaky up there. But stores soon filled with panorama-style depictions of different “Seat[s] of War,” perhaps inspired by these imagined views, and complete with crossed swords where battles had been.

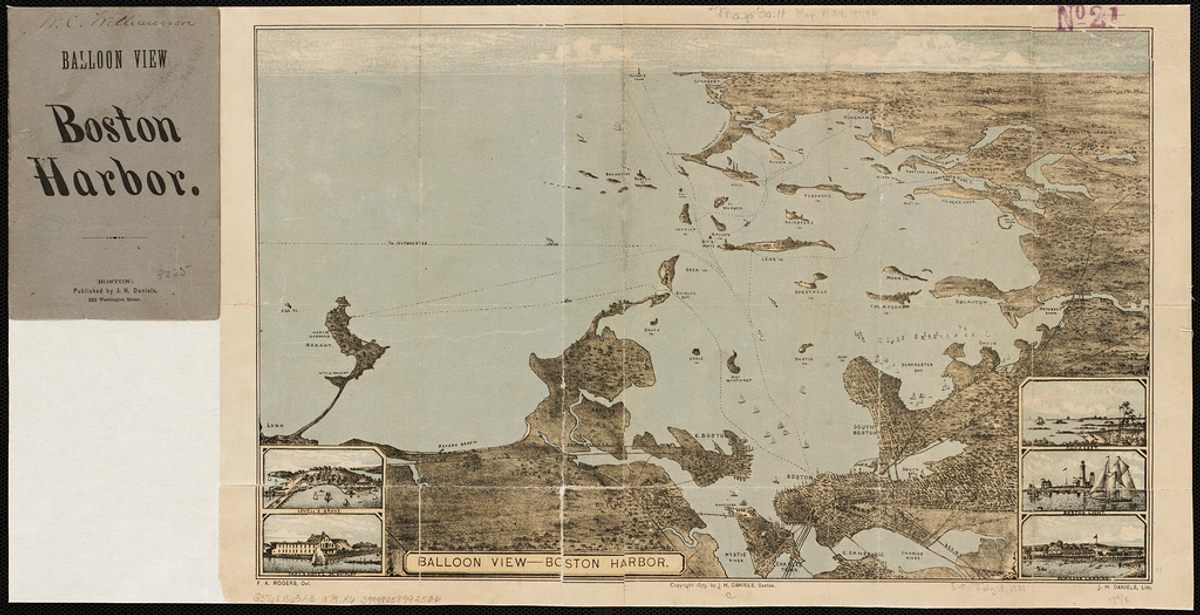

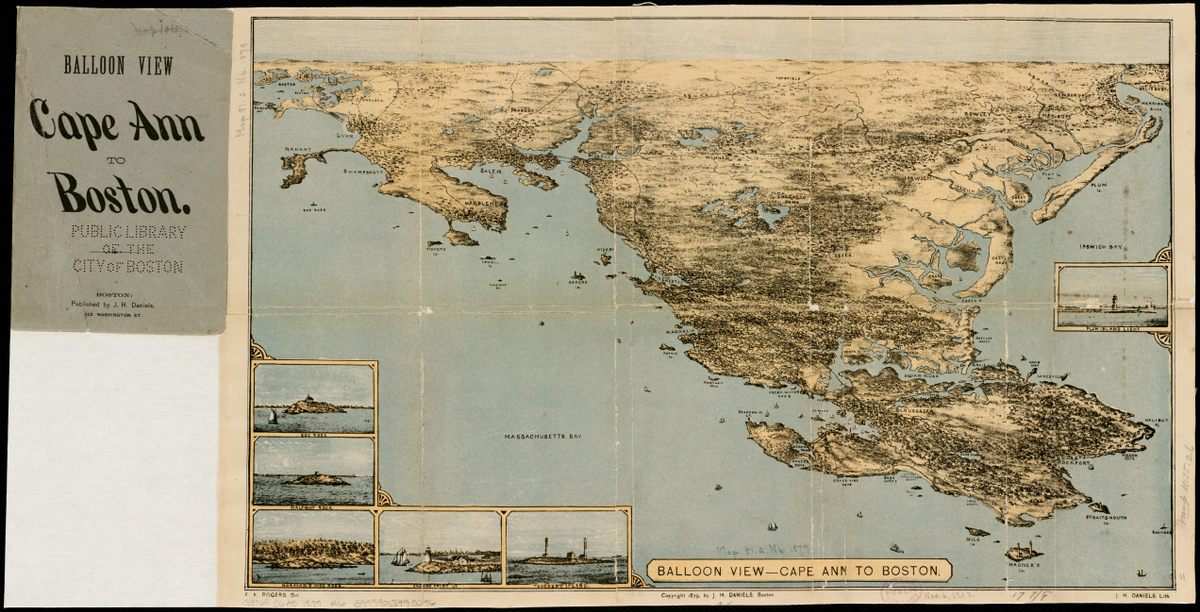

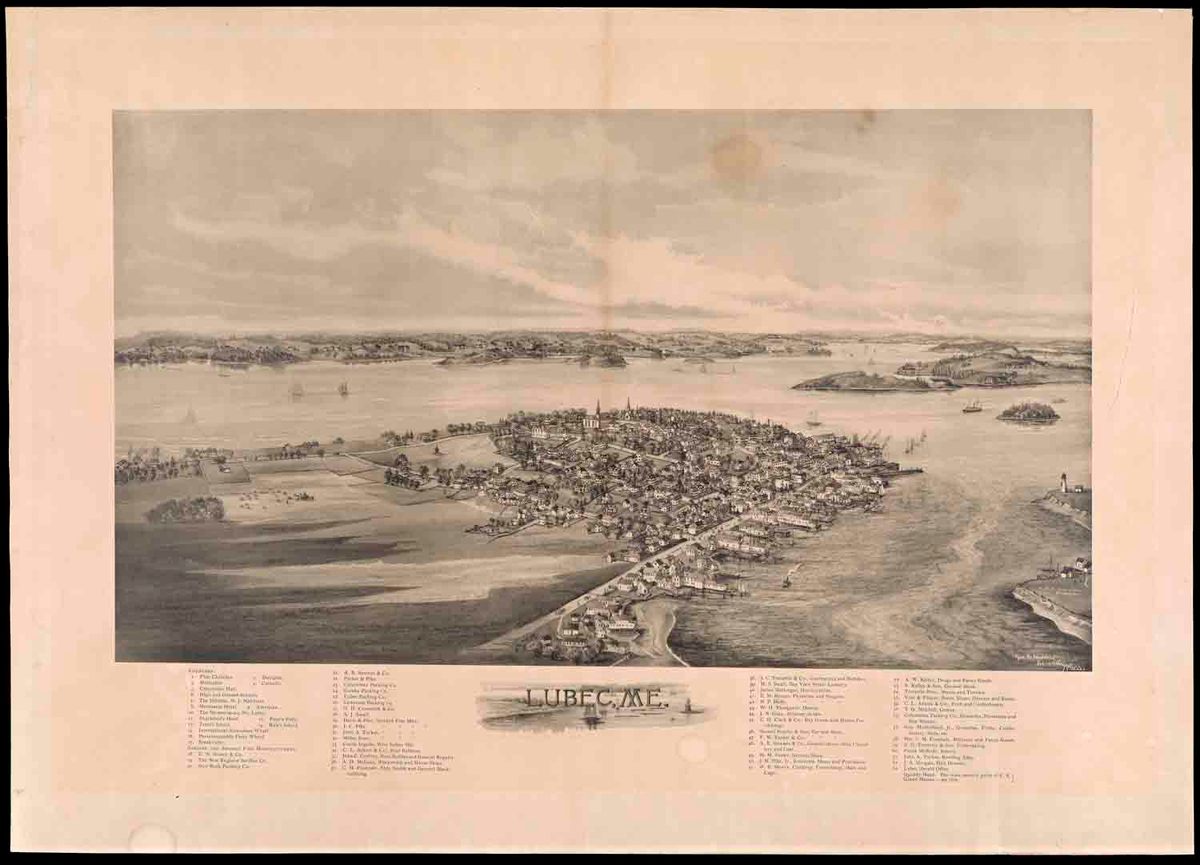

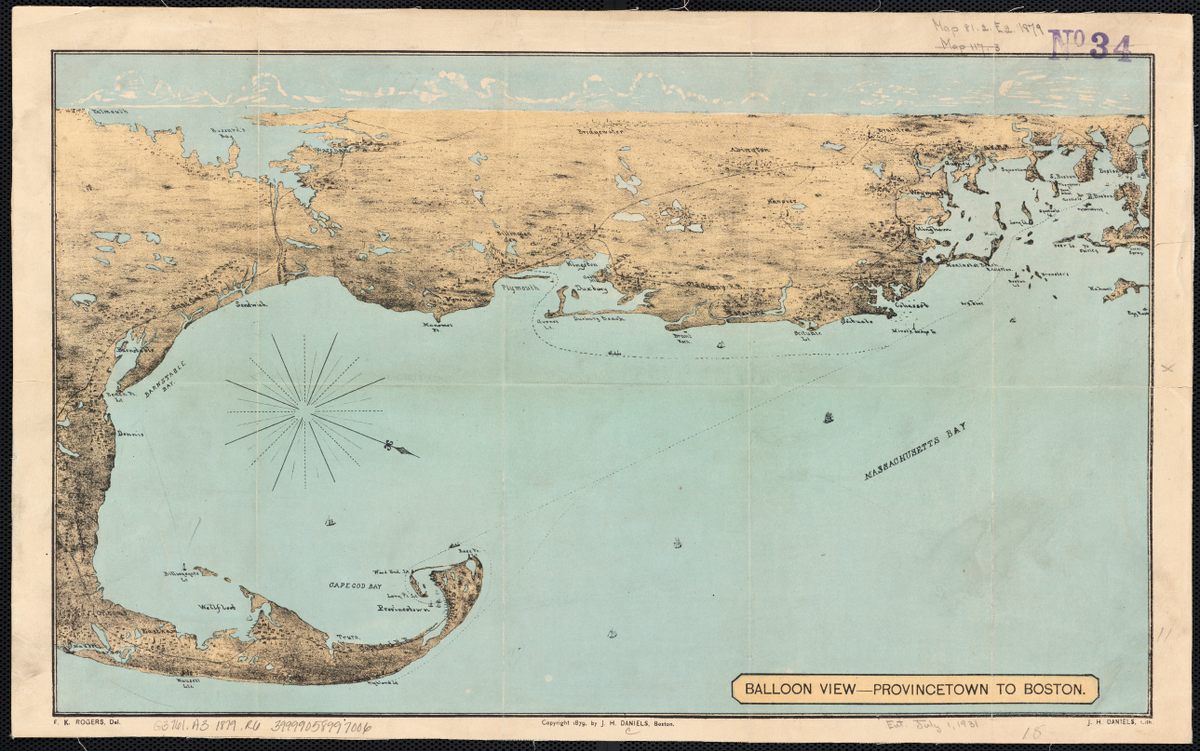

As the war ended and the century wrapped up, the balloon map found new purpose: as an invaluable tourism tool. The same qualities that made panoramas exciting and war understandable could make vacation hotspots look exotic, yet accessible. “[These showed] the landscape and coastal areas in a realistic, picturesque manner” while also highlighting area amenities, writes Matthew Edney of the Osher Map Library in an email. “Balloon maps” of various Massachusetts shore towns, created by draftsman F. Kimball Rogers in the late 1870s, sold for 25 cents and came with detailed information about beaches and summer homes. An 1896 map of Lubec, Maine looks like a toy town, with each local business carefully listed underneath.

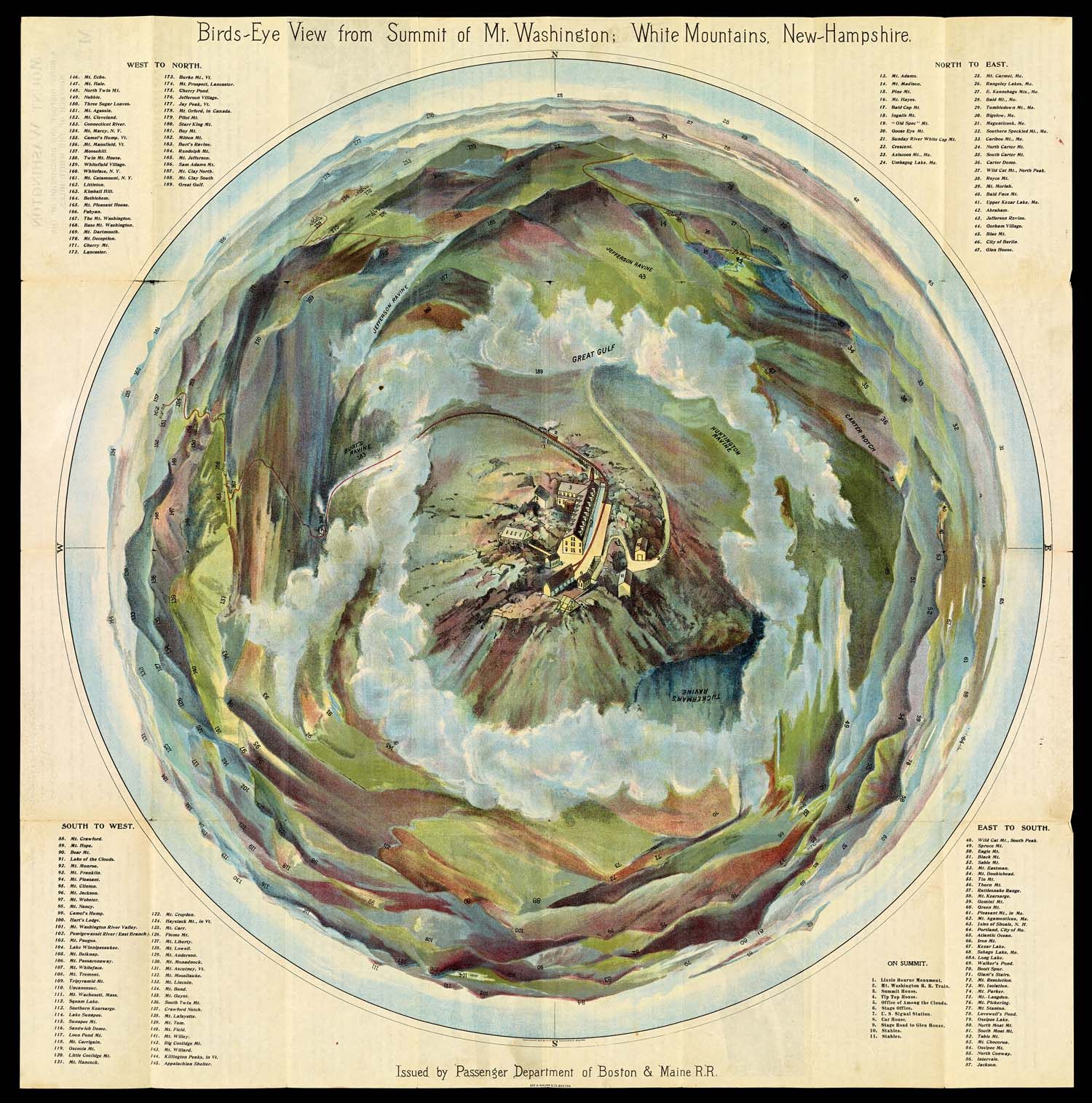

Although most of these maps were actually constructed from a ground-level point-of-view, their makers were happy to keep up the illusion of weightlessness. In 1902, the Boston and Maine Railroad gave to its passengers a Baldwinesque “Bird’s Eye View” map of the White Mountains—the summit of Mt. Washington front and center, with the other peaks and ravines, carefully labeled, swirling around it. With its painterly hues and unique perspective, the map is quite clearly a work of imaginative illustration. But it still came in a small booklet with a hot air balloon in the front.

Take a look at some more of these “balloon” and “birds-eye” maps, and enjoy this very particular view into the past.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook